Month: February 2012

Inflation Expectations and Probable Trap for Macro Stabilization

As of today, a majority of the negative consequences of the deep Belarusian currency crisis of 2011 seem to have been realized. Hence, the Belarusian economy is now ‘purified’ from main macroeconomic distortions and has a chance for sustainable long-term growth. Nevertheless, there are signals that some nominal and real inertia may generate new shocks for the national economy. From this view, the money market is of great concern, while interest rates signal maintained high inflation expectations. High and unstable expectations may entrap monetary policy and generate new shocks for the Belarusian economy. In this policy brief, we deal with a visualization of inflation expectations and argue for the necessity of a new nominal anchor in order to stabilize expectations for future periods.

In 2011, Belarus experienced its highest inflation and devaluation in modern history. These were consequences of the automatic macroeconomic adjustment determined by a number of both long- and short-term distortions in the national economy. Changes in prices and exchange rate adjusted real parameters towards their long-run equilibrium level. Hence, from a long-run perspective, one may interpret these adjustments as favorable since they ‘purified’ the economy from the macroeconomic imbalances that may have hampered growth. Furthermore, shifting from exchange-rate (XR) targeting to a managed float is another essential aftermath of the currency crisis. Economic authorities had to recognize that accommodative monetary policy (MP) was not compassable with XR targeting since it resulted in a considerable overvaluation of the real XR, and correspondingly, an incredibly large current account deficit. Thus, the new exchange rate regime may be argued to be a new automatic stabilizer for Belarus, providing the level of current account balance consistent with other macroeconomic fundamentals. Overall, the current stance of the national economy might be treated as a chance to “begin again from the ground up”. In this sense, the Belarusian economy as of today is sometimes compared to the Russian economy after its crisis in 1998, which then performed particularly high growth rates.

In our opinion, realizing the opportunity for a strengthening of long-term growth through structural changes undoubtedly should become a policy priority of Belarus in the near future. However, it should be emphasized that despite “purification” from major macroeconomic imbalances, there are still a long list of short-term challenges. In particular, one may stress the risks of expansionary policy revival; increasing external debt burden; growth in non-performing loans, which may undermine the solvency of the banking system; reduction of foreign demand due to shocks in global economy. These risks are more or less observable and may be monitored. Hence, the realization of one or the other shocks from this list might not come as a surprise, and economic authorities seem to at least realize this, and when possible, take prevention measures.

At the same time, another challenge seems to be more adverse and urgent; namely, the question of inflation and devaluation expectations. In economic theory, expectations play a crucial role in affecting behavior of economic agents. Recognition of the role of expectations at the money market determined intention to “subject” and stabilize these within modern monetary policy frameworks.

In Belarus, given the recent history of high inflation and devaluation, corresponding expectations of Belarusian economic agents are likely to be rather high. Moreover, shifting from XR targeting to a managed float has not yet resulted in provision of a new nominal anchor for the public.

For instance, disinflation was declared to be a priority goal, but there are no strict commitments on its numerical value, as well as in respect to procedures and mechanisms to provide disinflation trends. As of today, the Belarusian MP regime can hardly be classified as a standard regime. The MP Guidelines for 2012 assume indicative targets on international reserves, refinancing rate and the growth rate of banks’ claims on the economy. The latter witnesses the propensity to monetary targeting. However, the instable relationship between the monetary aggregate to be targeted and the ultimate goal (inflation), as well as the indicative nature of this commitment give rise to doubts in respect to treating it as monetary targeting. Furthermore, commitment on bank claims on the economy can hardly be treated as a nominal anchor for the public. According to the taxonomy of MP regimes by Stone (2004), Belarus is currently closer to the weak anchor regime, which assumes “no operative nominal anchor…and central bank reports a low degree of commitment… and high degree of discretion”.

Thus, our hypothesis assumes that there has been an adverse shock in inflation expectations due to weak nominal anchor and recent experience of huge inflation. If that is the case, this may be an additional source of shock for the money market, which may cause a new wave of macroeconomic instability. In order to make policy recommendations, this hypothesis needs empirical support. However, it is difficult to identify expectations in empirical analyses since this variable is typically unobservable and cannot be univocally measured. Instead, expectations are most often treated indirectly through other variables. Many central banks deal with the results of sociological polls on this issue, but these approaches may suffer from different economic meanings and measurements of inflation expectations by economic agents.

An alternative approach was proposed by St-Amant (1996) and extended by Gotschalk (2001), who base on famous Fischer equation representing current nominal interest rate as the sum of ex-ante real interest rate and expected inflation. Further, based on the approach by Blanchard and Quah (1989), structural vector autoregression (SVAR) between nominal and real interest rate is identified with a number of restrictions, which allows decomposing changes in the nominal rate to those associated with ex ante real rate and inflation expectations. The latter may be used as a measure of inflation expectations. Such a measure of inflation expectations assumes explicit economic meaning referring to the money market, i.e. the rate of future inflation, which will provide the, by economic agents, expected level of interest rate. Taking the data from statistics (not polls) and international comparability of such estimates are important advantages of this approach.

We applied this methodology to Belarusian data (nominal and real interest rate on ruble households’ deposits with a term more than a year). The obtained time series measure changes in inflation expectations in the current period for a period of the next 12 months. However, our goal is to visualize the level of inflation expectation and not changes in expectation. Therefore, we use the series in levels, choosing January 2003 as the base period (when National Bank of Belarus actually shifted to XR targeting regime), and assigned a zero level (as starting one) to it. The obtained series of inflation expectations is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Inflation Expectations in Belarus

The estimated series of inflation expectations show a decrease in 2003 – mid 2005, which may be explained by the effectiveness of the new nominal anchor (XR), and correspondingly the expected disinflation. The expectation of reflation in late 2005 till late 2007 may be explained by the more expansionary policy and changes in Russian preferences that took place during this period. After that, there was a period of stable expectation, which is likely to be explained by the credibility of the nominal anchor (nevertheless, there was a shock in late 2008 that is associated with the impact of the global crisis).

The most considerable shock took place in the beginning of 2010, which has a lack of intuitive explanation and might be associated with a phase of radically expansionary policy.

Finally, a new significant shock took place in late 2010 – beginning 2011 which might be associated with the visualized problems at the currency market at that time.

Currently, there is a very high level of inflation expectations and its increased volatility in the second half of 2011 seem to be of a great importance. It signals that economic agents do not treat price shocks as a single-shot, but mostly tend to consider it as a long-lasting process. Hence, the absence of a nominal anchor and the fresh memory of huge inflation seem to be responsible for the current high and instable inflation expectations.

Maintenance of high inflation expectations is a dangerous threat for the money market. Propagating inflation through expectations may be considered as a separate channel within the monetary transmission mechanism (along with interest rate, exchange rate and bank-lending channels). In other words, even without additional fundamental preconditions for inflation, inflation expectations may become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

However, during the last two months (December 2011 and January 2012) this adverse effect seems to have been suppressed by monetary authorities, as the monthly inflation rate reduced radically in comparison to average rate in May-November 2011. This is likely to be the outcome of the significant monetary policy tightening that has resulted in a sharp increase in nominal interest rates by banks. On the one hand, such nominal interest rate complies with the shocks in inflation expectations and real ex ante interest rate (the latter grew as well at the background of the crisis). In other words, current level of nominal interest rates will equalize ex post real rate with ex ante real rate if the actual inflation rate has been as high as current inflation expectations. But on the other hand, if actual inflation had been much lower than expected one (and it tends to be so, in case of keeping on conservative MP), ex post real rate would be much higher than the ex-ante one. For instance, such a situation has already been peculiar during December and January: according to our estimations, ex ante real interest rate in December was about 3.6% in annual terms (preliminary data on January shows that it in this month it is rather similar), but annualized ex post real rate for these months is about 30%.

This suggests that there is a trap for the monetary authorities. If they keep high interest rates, based on the expected inflation, the impact of expectations on actual inflation will be mitigated, but the losses, say in terms of output, will be high because of the extremely high ex post real interest rates. If the monetary authorities facilitated the rapid reduction of nominal interest rates, current nominal rates would not guarantee ex ante real interest taking into consideration the high inflation expectations, which would then constitute a severe shock for the money market. Hence, the mechanism of self-fulfilling prophecy would work.

Furthermore, the increased ex ante real rate (and high probability of even higher ex post real rate in national currency) could give speculative incentives for a number of economic agents. For example, many agents could increase the share of national currency in their savings portfolio, either avoiding buying hard currency (which took place during the peak of the currency crisis) for new deposits, or changing the nomination of their deposits to the national currency (i.e. selling the hard one). In a sense, this trend may be interpreted as the compensation of losses on ruble deposits in the last year, which is needed to revive the demand for such deposits. But in any case, these internal processes (along with restricting money supply by the National bank) influence the domestic currency market. Through this, the supply and demand are formed not only due to current and financial international flows. Hence, due to these incentives for hard currency supply and demand, the current value of the nominal rate may substantially deviate from the equilibrium rate. The latter may be defined as in Kruk (2011): the one that may clear the market immediately (given short-term trends in current account flows at the background of medium-term values of other fundamentals).

Figure 2. Actual and Equilibrium Exchange Rate

Note: For 2010Q1-2011Q1 official rate of the National bank is taken as actual nominal rate, for 2011Q2 the exchange rate at the ‘black market’ (used by internet shops), and for 2011Q3 ‘black market’ and later the exchange rate of the additional BCSE session are taken.

The assessments of the equilibrium exchange rate based on this methodology (Kruk (2011)) show that in the third quarter, the actual rate almost equals the equilibrium rate. For 2011Q4, all necessary data is not available yet, but an approximate assessment correction of the equilibrium rate of the Q3 for average inflation between Q3 and Q4 may be used (i.e. in real terms the rate should not have changed in order to sustain equilibrium). Such an assessment indicates that the actual rate in the Q4 is again overestimated by roughly 5-10% in comparison to the equilibrium rate.

At a first look, such an ‘overhang’ at the domestic currency market seems to not be a great problem. But along with the trap stemmed from the high and unstable inflation, this may contribute and propagate possible shock at the money market. Furthermore, this ‘overhang’ is due to speculative incentives, which in turn, are due to high inflation expectations. Hence, high and unstable inflation expectations are a prime cause of this ‘overhang’.

Finally, we may argue that unfavorable inflation expectations is a multidimensional problem, which generates grounds for shocks at the money market and entraps monetary policy at the current stage. Therefore, restraining inflation expectations must currently be an absolute and unconditional priority of economic policy.

This gives rise to the issue of which policy tools that are needed for solving this problem. Tight monetary policy alone may not be enough and/or its losses in terms of output may be unacceptably high, especially taking into account that keeping the Belarusian economy depressed is likely to cause huge migration and thus reducing the prospects for long-term growth.

Our view on the problem of inflation expectations supposes that they stem both from recent experience of very high inflation and the absence of nominal anchor. Inflation memory cannot easily be removed, but introducing a new nominal anchor seems to be worthwhile. Among possible options, given the desire to preserve autonomous monetary policy in Belarus, the introduction of inflation targeting (IT) is seen as inevitable. A shift to this regime is associated with plenty of obstacles and might not be realized immediately (Kruk (2008)). A gradual shift to IT through its intermediary phases (so called IT Lite) is more expedient and complies more with the requirement of obtaining new powers and capacities at the National Bank of Belarus.

Taking on more and more strict commitments in terms of inflation and implementing mechanisms and procedures peculiar for IT (the latter is even more important than commitments themselves) will increase credibility and public trust for the National bank. The other side of the coin involves decreasing and less volatile inflation expectations, which do not challenge monetary policy and facilitate low and stable inflation. Another advantage of IT is the possibility to mitigate price shocks.

Our main policy recommendation is therefore that it is necessary to shift to an IT framework as soon as possible, starting from exploiting the forms of IT Lite. The advantages of this step overweigh all the obstacles, including those associated with the reluctance of economic authorities to change institutional preconditions.

However, one important clause should be emphasized. Shifting to IT (especially gradually through IT Lite) does not guarantee that current high inflation expectations will be reduced automatically and immediately. In other words, it does not guarantee that the cost of reducing inflation in terms of output will decrease (though for the present Belarusian situation there are grounds to suspect that it would facilitate). For instance, Mishkin (2001) shows that “there appears to have been little, if any reduction, in the output loss associated with disinflation, the sacrifice ratio, among countries adopting inflation targeting… The only way to achieve disinflation is the hard way: by inducing short-run losses in output and employment in order to achieve the longer-run economic benefits of price stability”. However, an introduction of IT assumes that new shocks in inflation expectations may be prevented, and due to it, low and stable inflation will be more likely.

▪

References

- Blanchard, O., Quah, D. (1989). The Dynamic Effects of Aggregate Demand and Supply Disturbances, American Economic Review, Vol. 79, No.4, pp.655-673.

- St-Amant, P. (1996). Decomposing US Nominal Interest Rate into Expected Inflation and Ex Ante Real Interest Rates Using Structural VAR Methodology, Bank of Canada, Working Paper No. 96-2.

- Gottschalk, J. (2001). Measuring Expected Inflation and the Ex Ante Real Interest Rate in the Euro Area Using Structural Vector Autoregressions, Kiek Institute of World Economics, Working Paper No.1067.

- Mishkin, F. (2001). From Monetary Targeting to Inflation Targeting: Lessons from Industrialized Countries, World Bank, Policy Research Working Paper No. 2684.

- Kruk, D. (2008). Optimal Instruments of Monetary Policy under the Regime of Inflation Targeting in Belarus, National Bank of Belarus, Materials of International Conference “Efficient Monetary Policy Options in Transition Economy”, pp. 305-322.

- Kruk, D. (2011). The Mechanism of Adjustment to Changes in Exchange Rate in Belarus and its Implications for Monetary Policy, Belarusian Economic Research and Outreach Center, Policy Paper No. 004.

Is Regional Policy Effective in the Long Run? Learning from Soviet History

Regional inequality has been a pressing issue in many countries, and also between the countries of the European Union. Unequal economic development, where some regions develop successfully and prosper while other regions stagnate, is often viewed as a source of social instability and economic inefficiency. Many kinds of regional policy have been proposed in order to mitigate such a situation by promoting growth in lagging regions. The policies range from subsidies and favorable tax policies for business investment to large-scale government investment projects. The ultimate goal of all regional policies is to create an environment for sustainable growth in regions that have fallen behind. In theory it might appear that a policy, which is implemented during a specific period of time, would be sufficient to achieve sustainable development: subsidies or creation of infrastructure would lure firms into a region and create a favorable environment for economic agents (both firms and people). The temporary policy would create agglomeration externalities that would ensure sustainable development even after the policy is discontinued.

However, are such regional policies in fact successful? Researchers often observe a short-run impact, but it is less clear whether regional policy can make a difference in the long run. From the literature on historical “natural experiments”, we know that spatial structures of economic activity are very resilient to temporary impact. For example, the wholesale destruction and loss of life in WWII seems to have had little or no effect on the regional shares of population and manufacturing in the long run. On the other hand, significant and permanent (or long-lasting) changes to market access, such as the division ofGermanyafter WWII, do reshape the spatial economy in the long run.

Our study looks at the long-run patterns of Soviet city growth in light of Stalin’s industrialization and WWII. The Soviet government’s investment decisions during that period were dictated to a large extent by military strategy and ideology. Massive relocation of productive resources from west to east before, during, and after WWII represents a unique natural experiment, in which production factors were destroyed in some parts of the USSR, while new production facilities and infrastructure were created in other regions of the country. Using a unique dataset, we test whether Gulag camps, wartime evacuation of industry, and location near the war front had a long-run effect on city size.

In the 1930s-1950s, Stalin’s system of penal labor camps (the Gulag) was widely used as a source of cheap labor, especially in remote locations where there was no other available labor force. Penal labor was used in a variety of sectors (logging, mining, manufacturing and construction). Presence of a camp near a city or town usually meant that this location was chosen by the Soviet government for an investment project. We trace the impact of having a camp nearby on city growth from 1930 to the present day.

Evacuation of enterprises from western to eastern regions of the USSR (to avoid their possible capture by the advancing German army) is traditionally named among factors that determined post-war growth of cities in the Urals andSiberia. Indeed, data show that the majority of evacuated enterprises never returned to their original location in the westernUSSR. Western cities that sent enterprises into evacuation often lost their significance in the immediate post-war period. We test whether evacuation affected the growth of cities in the longer run, ceteris paribus.

Unfortunately, no detailed data on deaths and destruction in Soviet cities during WWII are publicly available. We therefore measure the impact of wartime damage by constructing a set of indicators for cities that were occupied or were close to the front line during WWII.

The results show that (controlling for pre-war city size, rate of growth, and geographical location) occupation and location 30 km or 200 km from the front line do have a negative and statistically significant effect on city size by 1959. However, this effect disappears by 1970. This is consistent with findings forJapanandWestern Germany, where pre-war trajectories of city growth were restored after 25-30 years.

Surprisingly, the result is roughly the same for cities which hosted evacuated enterprises. Controlling for pre-war size and growth rate, geography and presence of Gulag camps, cities that received evacuated plants grow faster until 1959, but the difference is not statistically significant in 1970 and later. Thus, contrary to the commonly held belief, the effect of evacuation was only temporary.

By contrast, the presence of a Gulag camp increases city size in a long time horizon. Gulag cities grow faster not only in the 1930s-1950s when the Gulag system was operational, but also in the 1970s and 1980s. On average, the Gulag effect only disappears in the 1989 population census.

Specialization of the camp also makes a difference. Effect on city population from a camp where prisoners were involved in agriculture or logging is short-lived. Such camps were not used to build capital or infrastructure, so the nearby cities did not become more attractive for free labour. However, if a city had a camp where prisoners worked in manufacturing, mining, or construction of production facilities or housing, its population increased permanently. Compared with the best match from a control group (a city of similar characteristics, but without a Gulag camp), such a city accrued 50% more population, and this difference remains statistically significant even until the census of 2010.

Overall, the evidence on Soviet city growth supports the common finding: the direct effects of WWII were relatively short-lived. The experience of enterprise evacuation shows that one-shot relocation of production factors by the state also fails to produce robust changes in the geographical redistribution of economic activity in the long run. However, when the Soviet government established new industrial centers in the eastern parts of theUSSR, and made massive investments in production facilities and infrastructure using Gulag labor, it managed to permanently shift the geography of economic activity. This example illustrates the size and scope of impact that is required to affect economic geography in the long run.

▪

Who Needs a Safety Net?

One definition of safety net found on the internet is the following: “a net placed to catch an acrobat or similar performer in case of a fall”. This brings to my mind the thrilling performances I saw at the circus when I was a child and I have to admit in most cases there was a safety net. Only in some rare occasions it was removed and the increased tension became palpable. We knew that only the best acrobats could dare performing in those conditions since the slightest mistake or distraction could lead to disastrous consequences. Born in this context, the term safety net has soon been extended beyond circuses. The same internet source, right below the standard definition adds: “fig. a safeguard against possible hardship or adversity: a safety net for workers who lose their jobs”.

Imagine you are a European worker in a time of crisis. You are the only breadwinner in your family and you become unemployed. The situation of your family is going to worsen significantly, but you know that – at least for some time – you and your family will be able to survive thanks to your unemployment benefits and to other forms of social support. In the meantime, hopefully, you will be able to get a new job – maybe thanks to the help from a public employment agency – or will at least be admitted into some publicly sponsored training program increasing your probability to get a new job.

Imagine that, instead of being fired, you get sick. Luckily most of the costs for your care will be covered by the public healthcare system. You will continue receiving your salary (with a reduction as the length of the period of sickness goes beyond a certain number of days) for at least a few months, typically until you can go back to work. If your illness is really serious, at some point you will not receive compensation but you will keep your job unless you stay away from your workplace continuously for a very long period. Should you lose your job, you will still be able to rely for a while on unemployment benefits and on additional forms of social support. Your family will be suffering of course, but at least you will be able to “gain some time” to find a solution.

Now imagine a different scenario. You lose your job. You get one month severance pay but no unemployment benefits. The labor market is hardly creating new jobs, so you have a high probability of not finding a good job and will have either to accept to be unemployed for a long period of time or to work in badly paid temporary jobs, maybe in very dangerous working places (because nobody is in charge of checking working conditions). In case you choose not to risk and to try looking for safer jobs, most likely during your unemployment period you will not receive any training and certainly no support from (non-existing) public employment agencies.

Or, what if you are sick and all healthcare costs fall on you. If you have a private health insurance you get some assistance. If not, you have to dissave in order to get some treatment. You receive one month of salary, after which your employer is free to fire you without having to give you any compensation. So you suddenly find yourself sick and not only unable to help your family but being a burden for it, with no public support and no income. To be fair, you might receive some sort of assistance, after you have applied to the government for support as a needy household if your situation has deteriorated so much that you cannot ensure even your subsistence (maybe by selling assets). However, this support is typically not that high.

This second case is not that of a fictional country. It is a representation of the conditions of most workers in Georgia.

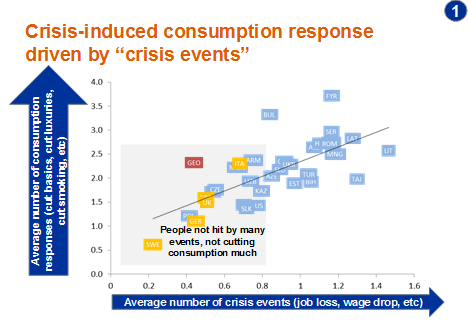

If you keep this in mind, you will not be surprised looking at the following pictures taken from the latest EBRD (European Bank for Reconstruction and Development) Transition Report, titled: “Crisis and Transition: the People’s Perspective”. The tables and pictures included in the report are based on a series of household surveys conducted by the EBRD in a number of transition countries plus a few selected countries of Western Europe. The aim of this study was to study how the crisis had affected household’s welfare in order to draw some conclusion about the potential vulnerability of countries and households to future crises.

Figure 1.

Source: EBRD Transition Report 2011

In this first picture Georgia (in red) stands out as very much above the regression line. It is what is defined as an “outlier”. In this case, being an outlier means exactly that Georgian households, despite having been themselves hit by a relative smaller number of negative events, appear to have suffered much more than households in similar situations in other countries. In other words, they were forced to cut their consumption much more than households in other countries.

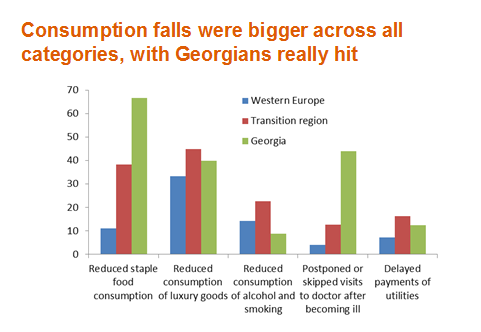

The second picture (below) allows us to see where Georgian households had to cut their consumption. Of course, cutting the consumption of luxury goods is not the same as cutting the consumption of food or healthcare. Looking at the second picture, the situation in Georgia appears even worse. Most households have had to cut exactly where one would hope they had not to: staple food consumption and visits to doctors.

Neither of these cuts bode well for the future of Georgian households, as they are likely to have long lasting (negative) effects. Especially as a new world crisis seems approaching.

Figure 2.

Source: EBRD Transition Report 2011

Why this discussion about Georgia and safety nets? The reason is because for some time now Georgia has been presented consistently as a showcase country with an impressive reform track (including an extremely liberal labor market reform that has drastically reduced all forms of workers’ protection) and equally impressive growth rates.

Much less has been said about how Georgian people have been affected by these reforms. For sure the picture that emerges from the EBRD study is of a country where households are extremely vulnerable to any slowing down of the economy or worsening of the macroeconomic conditions, much more than in most other countries.

Again, looking at the EBRD study, we can see that this is related to at least two factors: on the one hand the extremely weak safety net provided by the state; on the other hand, the limited success (so far) in translating high growth rates into a substantial amount of new, “good quality” jobs. This is what led the EBRD, after presenting these results to suggest the following two key priorities for the Georgian government: “…to create a basis for export led growth… […] but also to establish an effective social safety net”.

I would like to conclude with my personal answer to the question: “who needs a safety net?” The answer is a lot of people, I would say, especially in times of crisis like the current. After all, not even the best acrobats would dare to perform all the time without it, especially when they are trying their most dangerous performances for the first time and when preconditions are less than perfect. Why? Because the cost of failure would be too high. Like in the case of acrobats – even more, as they are not risking their own lives – policy makers have the responsibility of taking into account in their evaluations what could go wrong and think of ways to minimize negative impacts on the population.

Most economists would agree that only a sustainable increase in the welfare of citizens (including the most vulnerable ones) is the true sign of development of a country in the long run. Assuring this, as someone sometimes seems to forget, requires also creating and maintaining – especially when markets are less than perfect, a solid social safety net.

▪

The Distributional Impact of Austerity Measures in Latvia

For a country of its size, Latvia was mentioned in the last decade’s macroeconomic discourse remarkably often: first, for its exceptional growth up to 2007, then – for a dramatic GDP contraction in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, and for the so-called “internal devaluation” policy that was the cornerstone of Latvia’s recovery strategy. Now, when GDP recovery is underway for 9 quarters, Latvia is held up as an example of a country that paved its way out of the crisis with decisive and timely budget austerity measures. The size of budget consolidation package was remarkable, reaching almost 17% of GDP in 2008-2011. Today, when there is so much talk about austerity in the context of the Eurozone debt crisis, Latvian consolidation experience is of particular interest. In this brief, we are looking at the distributional impact of selected implemented austerity measures, using a microsimulation tax-benefit model EUROMOD. Our results suggest that the impact of these measures is likely to have been progressive, meaning that rich population groups are bearing a larger part of the burden.

From Boom to Recession

The “Baltic Tigers” – a term coined to praise the Baltic countries for their dynamic development in the 2000s, especially after their accession to the EU in 2004. During 2004-2007, average annual GDP growth in the Baltics exceeded 8% (in Latvia average growth was 10%). The growth was to a large extent driven by an externally financed credit bubble, leading to overheating of the Baltic economies: inflation was skyrocketing, unemployment was at historically low levels, and current accounts posted double-digit deficits. Before the outbreak of the crisis, the Latvian economy was in the most vulnerable position: Estonia was better situated thanks to prudent fiscal policy implemented in the “good” times, whereas Lithuania was less exposed thanks to its private sector being relatively less indebted.

The growth slowdown in Latvia began in 2007 and was initially triggered by the government’s adopted “anti-inflation plan” and the two of the biggest banks’ actions aimed at restricting credit expansion. Altogether, this initiated a decline in real estate prices. By December 2007, the average price of a square metre in a standard-type apartment in Riga had fallen by 12% from its peak in July (Arco Real Estate, 2008). Construction, retail trade and industrial production growth slowed down in the second half of 2007. GDP quarter-on-quarter growth approached zero by end-2007 and turned negative in the 1st quarter of 2008. In August 2008, the second largest Latvian commercial bank, domestically owned Parex Bank, faced deposit run and was unable to finance its syndicated loans, and in November 2008, the Latvian government took the decision to nationalize the bank. By the 3rd quarter of 2008, GDP quarter-on-quarter contraction exceeded 6%. The budget revenues lagged behind the expenditures, resulting in a gradually growing budget deficit, which reached about 5.5% of GDP in the 3rd quarter of 2008 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Year-on-year growth of general government budget total revenues, tax revenues and expenditures, %; seasonally adjusted budget balance, % of GDP

Source: Eurostat, authors’ calculations

In circumstances where the fiscal position was quickly deteriorating but world financial markets were frozen, the Latvian government was forced to seek financial assistance from international lenders. After tough negotiations in November and December 2008, Latvia received a 7.5 billion euro (about 1/3 of GDP) bailout facility from the IMF, the European Commission, the World Bank and the Nordic countries. Latvia received the funding in a series of tranches, with the transfer of each tranche being subject to implementation of a strict reform package agreed with the lenders.Given that introduction of the euro in 2014 remained the Latvian government’s target, one of the key elements of the reform programme was maintaining the lat’s peg to the euro. Therefore, the Latvian government had to accept especially strict and wide-ranging budget consolidation measures.

Budget Consolidation

The total size of budget consolidation achieved in 2008-2011 was impressive: overall, the fiscal impact of the reforms is estimated at 16.6% of GDP (Ministry of Finance of Latvia, 2011). Under the pressure of international lenders, budget consolidation was front-loaded and was achieved astonishingly fast – the fiscal impact of the reforms implemented in 2009 reached almost 10% of GDP, whereas the impact of 2010 and 2011 year measures was much smaller – 4.1% and 2.6%, respectively (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Size of the implemented consolidation measures and budget deficit outturn, % of GDP*

* Budget deficit in 2011 is the Bank of Latvia’s autumn forecast

Source: Ministry of Finance, Bank of Latvia, Eurostat

Yet the way the consolidation was done was rather chaotic. The 2009 consolidation was mainly implemented by expenditure cuts, including strong wage and employment reductions in the public sector (public pay and employment cuts were continued in the following years, wages were cut by 15-20% in each round and most bonuses were abolished). On the revenue side, the government stuck to the goal of shifting tax burden from labour to consumption, thus the consolidation was mainly achieved by raising indirect taxes, while the personal income tax was reduced. Another line followed by the government at the time was to strengthen support to those affected by the crisis, for example, the duration of unemployment benefits was increased.

Nevertheless, by the time preparation of the 2010 budget started, it became clear that in circumstances of continuing GDP fall and peaking unemployment (in 2009, GDP fell by 17.7%, and the rate of unemployment reached 17.1%), the reduction in labour taxes could not be sustained while the social budget could not bear the burden of growing expenditures. Consequently, the reduction in the personal income tax was reversed (the tax rate was raised even above the pre-crisis level). To consolidate the social budget, the government implemented an across the board cut by introducing ceilings on the size of many benefits. In 2011, the tax burden on labour was further increased by raising the rate of mandatory social security contributions.

Budget consolidation was done under the pressure of the crisis and the reform package was designed in a great rush. What also may not be disregarded, is that the three years – 2009, 2010 and 2011 – were election years in Latvia: in 2009, there were local government elections, in 2010 – parliamentary elections and in 2011 – parliamentary re-elections . Elections have arguably affected the composition of implemented austerity measures. Thus, in June 2009, just ten days after local government elections, amendments to the Law on State Pensions were passed, which stipulated that old-age pensions should be cut by 10%, but pensions to working pensioners should be cut by 70%. This decision caused a strongly negative public reaction and on December 21, 2009, the Constitutional Court ruled that the government’s decision was unconstitutional arguing that the state must guarantee peoples’ right to social security. In the following budget consolidation rounds, even in the face of convoluted IMF recommendations to find a constitutional way of ensuring sustainability of the pension system (IMF, 2010), the government remained strictly opposing any pension cuts.

The mix of implemented reforms is crucial not only because it determines the effectiveness with which the budget consolidation is achieved. What is equally important is that the mix of reforms affects the distribution of costs of the crisis and shapes the economic recovery path. The consequences of the crisis – the dramatic rise in unemployment and wage reductions in the private sector – had a strong impact on incomes, yet policy makers can do little to directly affect this process. On the other hand, policy makers can offset or aggravate those effects by implementing reforms, such as those that made up the austerity packages. In this brief, we assess the distributional impact of selected austerity measures, which were implemented in 2009 – 2011.

Modelling Approach and Limitations

We use the Latvian part of the tax-benefit microsimulation model EUROMOD and follow a similar approach as that taken by Callan et al (2011). We limit our analysis to reforms in direct taxes, social contributions, and cash benefits . In particular, the following austerity measures are included in the analysis:

- removal of income ceiling for obligatory social insurance contributions (in 2009);

- increase in the rate of social insurance contributions for employees, employers, and self-employed (June 30, 2011);

- reduction of tax exemptions (July 1, 2009);

- increase in the rate of personal income tax (2010);

- introduction of benefit ceiling for unemployment benefits (2010), maternity, paternity, and parental benefit (November 3, 2010);

- cuts in state family benefit (2010);

- cuts in child birth benefit (2010);

- reduction in the amount of parental benefit by limiting eligibility to non-working parents only (May 3, 2010);

- making stricter income assessment criteria for guaranteed minimum income (GMI) and reducing amount of the GMI benefit for some groups (2010).

We assess the distributional impact of these austerity measures by comparing two alternative scenarios:

- the baseline scenario – simulation of 2011 tax-benefit policy system (with austerity measures implemented), and

- the counter factual scenario – simulation of tax-benefit policy system that would have emerged in 2011 in the absence of austerity measures.

If a policy was changed as a part of the austerity package (e.g. income tax increase), we implement a pre-austerity policy (e.g., reduce the income tax to its pre-austerity level). However, if the changes in the policies were regular (e.g. an increase in minimum wage that was planned long before the discussion of austerity measures had started) or not related to austerity measures (e.g. increase in duration of unemployment benefit) we include them in the counterfactual scenario, as well as in the austerity package scenario. By defining the counterfactual scenario in this manner we focus on the impact of austerity measures only holding other things equal.

Despite Latvia is one of the countries where the size of the austerity package was especially large, the distributional effect of the implemented measures has not been analysed neither before nor after the policies had been implemented. Until recently Latvia didn’t have a national microsimulation model which could be used to assess the impact of taxes and benefits on household income. This paper is the first attempt to do this.

However, our analysis is subject to some drawbacks. First, EUROMOD’s input data is based on the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions 2008 (with the income data referring to 2007). We adjust 2007 incomes up to 2011 using updating factors based on the aggregate evolution of such incomes according to national statistics. However, we do not adjust for the changes in the labour market that happened during this period. Therefore, we estimate the effect of austerity measures on data that represent the population with pre-crisis labour market characteristics (e.g. relatively low number of unemployed people).

Second, the analysis is limited to the direct impact of the implemented measures, disregarding the secondary effects such as e.g. behavioural responses of people on the implemented policies.

Results

The simulation results suggest that the impact of the analysed austerity measures was progressive with top income groups being the most affected (see Figure 3). The six countries considered in Callan et al (2011) show different degrees of progressivity: Greece demonstrated a clearly progressive impact, while Portugal was the only country where the effect was regressive. The result for Latvia is likely to be a consequence of introduced ceilings on contributory benefits, as well as the increases in income tax and social insurance contributions. While income tax in Latvia is flat (except for a relatively small untaxed personal allowance), the lowest income deciles contain proportionately more unemployed people and pensioners.

Figure 3: Percentage change in household disposable income due to austerity measures by income deciles

Source: based on own calculation using EUROMOD

Higher progressiveness was observed for households with children (see Figure 4), which is explained by the introduction of ceilings on child-related contributory benefits. At the same time, the impact on the households with elderly was more even.

Figure 4: Percentage change in household disposable income due to austerity measures for different types of households by income quintiles

Source: based on own calculation using EUROMOD

While the introduction of austerity measures made all income groups poorer, progressivity of the impact reduced income inequality. The Gini coefficient of the counter factual scenario is 1 percentage point higher than that of the base scenario. After implementation of the austerity measures, the poverty line decreases because the median income decreases. As a result, poverty rates using relative poverty lines decreased. The poverty rate of the elderly was affected the most, because pension income was not cut and pensioners became relatively better off as compared to other population groups. However, if measured against the fixed poverty threshold, the poverty rate increased in all population groups (see Table 1).

Table 1: Poverty rates and Gini coefficient before and after implemented austerity measures

Source: based on own calculation using EUROMOD

Concluding Remarks

The austerity measures analysed in this paper have had a progressive impact, with the richest population groups likely to be bearing most of the costs. This result should be interpreted with caution. It should be taken into account that we do not model all of the austerity measures that were implemented in 2009-2011. E.g., we do not model the impact of changes in VAT rates, which is likely to have been quite strong and regressive.

Latvia is a society with extremely high income inequality. For example, the income quintile share ratio calculated by the Eurostat (S80/S20), which measures income inequality, in 2009 was the second highest in the EU (6.9 as compared with an EU average of 4.9). It is unlikely that the progressive impact identified in this paper will significantly reduce income inequality gap in Latvia relative to other European countries.

References

- Arco Real Estate (2008). Real estate market overview (Sērijveida dzīvokļi, 2008. gada decembris)

- Callan, Tim, Chrysa Leventi, Horacio Levy, Manos Matsaganis, Alari Paulus & Holly Sutherland (2011). “The distributional effects of austerity measures : a comparison of six EU countries”, Social situation observatory, Research note 2/2011.

- International Monetary Fund (2010). Republic of Latvia: Second Review and Financing Assurances Review Under the Stand-By Arrangement, Request for Extension of the Arrangement and Rephasing of Purchases Under the Arrangement and Request for Waiver of Nonobservance and Applicability of Performance Criteria. IMF Country report No. 10/65, March 2010.

- Ministry of Finance of Latvia (2011). Budget consolidation in 2008-2011 (Veiktā budžeta konsolidācija laika posmā no 2008.-2011. gadam)