Tag: conflicts

Effects of Civil Confrontation in Social Media

This paper describes the practices of civil confrontation which can be found in social media (analyzing the cases of the Ukrainian segment of Facebook). The research shows that such practices can be used by interest groups to deliberately affect target audiences in certain ways and thus exacerbate civil confrontation or to expand its scope. Psychological effects of such practices for the society include monotony, ambivalence, desensitization and alertness. These effects can be used either to distract the attention from a certain issue or to enhance social mobilization, to reduce protest potential or to push large groups into impulsive actions, to impose contradictory ideas or to stimulate society to rethink values.

Civil Confrontation in Ukraine

Considering the warfare going on in Ukraine and the consequent state of society, it is important to clearly define what is going on between large social groups.

Figure 1. Continuum of Conflicting Sociopolitical Processes

A useful way to structure our thinking about these processes may be to use an approach to sociopolitical conflict presented in Iarovyi (2019), which suggests that the continuum of conflicting sociopolitical processes has 4 stages, as illustrated by Figure 1. In what follows we concentrate on the second stage, which is civil confrontation. Civil confrontation is defined as a form of intra-group confrontation in the society marked by a crystallization of value conflicts between opposing sides. It has the potential to escalate into other forms of conflict interaction as indicated by Figure 1. Unlike social tension, which is the earliest stage, the confrontation has an articulated ‘enemy’ image and identity. However, it is not as deep as a social conflict which has systematic and deep roots and exists in the framework of problems connected with values. It is also far from being a civil war since it does not include a military component and does not assume a dehumanization of the opponent.

Nevertheless, differences between the stages are rather vague. Within Ukraine one can observe social tensions between certain groups (such as civil servants of the “old generation” and new employees), social confrontation (e.g., between supporters of certain presidential nominees) and social conflict (e.g., between the believers of Russian and Ukrainian Orthodox Churches). The aggravation within this continuum occurs as a gradual buildup of the counteraction and change of the conflict gradient to a deeper one. For the society it might be beneficial to minimize the aggravation and identify the conflicts in their early stages. A simple way to identify conflicts is by studying communications in social media. In my dissertation, which is the basis for this policy brief, I perform this exercise.

Communication of Civil Confrontation

Sociopolitical conflicts are developing via communication, which is the linguistic representation of a conflict. The latter thrives via group polarization – transforming heterogeneous opinions of people into mutually exclusive opposing positions. To define the conflict of discourses in the Ukrainian segment of social media, it is necessary to consider both features of the modern Ukrainian political discourse in general and specific features of communication in social media.

Markers of Civil Confrontation in Ukraine

The overview of political conflicts in Ukraine allows me to define the general characteristics of Ukrainian political discourse which influence the growth of confrontation. They include (1) the exploitation of ethnic and civic identities; (2) the impact of the external (overseas) interest groups; (3) difficulties with defining the stage and type of the ongoing conflicts and (4) a lack of proactive work of the government on reducing the risks of conflict. These markers were taken into account during the research as the defining framework of the practices of civil confrontation, and they are attributed to a smaller or larger extent to the cases which were studied.

Characteristics of the Discourse in Social Media

In the context of competing discourses, communication in social media needs to be pragmatic and focused on broadcasting the own agenda of writers, otherwise a user who is overwhelmed with information from different sources will be distracted. Moreover, this communication should be interactive and cooperate with the audience in real-time to improve its impact (Westcott, 2008).

Communication in social media is often much more intense than in the real life. While people do not normally enter discussions in social media to “wage wars” (Whiting and Williams, 2013), the environment of the Internet itself is characterized by a weaker level of censorship and self-censorship, the absence of limits that restrict participants, quick responsiveness, scattering attention, a lack of real contact, interruption of public communication of two people by third parties, anonymity etc. Thus, communication in social media is less restricted for negative reactions of participants, less productive and at the same time more aggressive.

Psychological Practices of Civil Confrontation on Facebook

The psychological practices of civil confrontation are defined as a set of established methods and techniques within the community which allow an individual to engage in interactions of social institutions and change one’s own psychological states and processes. In the process of reproducing such practices in communication, the emotions, settings, stereotypes, and value orientations of the communicator are changed.

The research of such practices in Ukrainian social media used the critical discourse analysis (CDA) model by Norman Fairclough (1992), with the selection of 6 cases that differ in the intensity of verbal confrontation, the intensity of the discourses’ struggle in the virtual environment and the spread of discourses outside the virtual environment.

The source of empirical material are Facebook accounts of users who take active role in political life and communication in Ukraine. We select Facebook firstly since this platform in Ukraine is highly politicized and represents various views of political communicators who are often absent on YouTube, Twitter etc., and secondly, it publishes large texts, sometimes with a strong visual component, which allows to utilize the CDA comprehensively.

Effects of the Civil Confrontation

Monotony

The effect of monotony, or the reduction of motivation to control the activities and participate in social life, is reproduced due to excessive exploitation of some discourses in society.

The first case in which this effect is present is the story of Ukrainian boxer Oleksandr Usik who took part in a fight in Moscow, the capital of the aggressor state according to Ukrainian legislation. Some parts of the Ukrainian community met this event with strong condemnation. Sports and culture are traditionally considered the elements of “soft power”. Thus they are often used (or believed to be used) for political purposes. However, citizens who are less politically motivated often tend to doubt the political ideologies and put their personal sympathies to a certain person in the first place. The social media communication regarding this case was characterized by a segregation of community members depending on their belief in the statement “sport/art is outside of politics”, and caused numerous arguments between communicators. At the time, this very situation made more and more people voice their tiredness of the war (which is subconsciously perceived as the reason for the argument). It leads to the gradual implantation of the idea that “the war is the case of the politicians, and the peoples of Ukraine and Russia are friendly”, and could strengthen the position of pro-Russian politicians in Ukraine. The implantation of this idea is beneficial for Russia, as it lowers the loyalty of Ukrainians to their own state and discredits the authorities.

The second case relates to public protests of the Ukrainian opposition in 2017-2018 which never caused a really strong reaction of the ordinary citizens. Discursive instruments used to involve more people into protests (the famous phrase “Kyiv, get up!” which was used during Euromaidan in 2014) did not work since the society was tired of regular protests in 2016-2017 on every slightest occasion, each of them labelled “a Third Maidan” by the organizers. The monotony “filled” the public discourse with unnecessary information, people became tired of protests and manipulations, and the protests became marginalized. Thus, the monotony effect could be used for the diversion of attention, the reduction of the protest potential or the formation of the social “fatigue” (sharp decline of the ability and motivation to perform the social roles and functions or stand for the position). Getting out of this state is possible if the rhythm of the information supply changes and its foci are shifted, which will lead to new reactions and roll the discourse out, making it topical once again.

Ambivalence

The ambivalence, or the duality of the attitude of the same person to the same object/phenomenon, instead of monotony, leads to the production of public anxiety and nervousness. It was identified on the case of “derusification”, when one prominent Ukrainian official labelled Soviet and pre-Soviet poets and writers (V. Vysotskiy, V. Tsoi, M. Bulgakov) as the “tentacles of the Russian World” (i.e. Pax Russia).

The discussions over this case not only intensified contradictions among participants, they also led to the expansion of civil confrontation. While in the previous case with the boxer, the incitement of the hostility on the everyday level failed as the issues are rather unimportant, in case of famous poets and singers the incitement affects deeply rooted notions and nostalgia of the communicators and is much more efficient. With the growing hostility between communicators of opposing sides, it leads to disorganization of thoughts of hesitant people (e.g. those who have warm feelings about the Soviet culture and sub-culture despite supporting Ukraine in its war with Russia). As a result, communicators tend to be more nervous when making decisions and taking actions (physical actions or discursive). Thus the ambivalence effect could be used to push people to commit impulsive actions and diminish their rational thinking. Reducing its negative effects is possible via engaging the society into a dialogue, promoting compromise proposals and sticking to the principles of mutual respect in the process of communication.

Desensitization

The effect of desensitization, or diminishing the emotional responsiveness of the society to violent actions, arises from the practices of discourse discreditation and determining the boundaries of what is permitted, and is connected primarily with the loss of sensuality by the communicators. It was identified in the case of attacks on Roma people in Ukraine which were widely criticized on the official level but considered quite normal by a large amount of “ordinary people” in social media. The justification of the violence and lack of mass condemnation of the aggressive actions raise the threshold of sensuality in the society which leads to tolerating violence against certain groups (in this case – ethnic groups).

The toleration of violence could be further extended to other groups (such as political opponents). If this effect is implemented gradually, the negative consequences may not be visible until it is too late. Minimization of the negative impact is possible via disclosure of information about such practices, drawing attention to them and articulating the importance of preserving the universal human values.

Alertness

The effect of alertness, or the state of being highly aware and ready to face confrontation, arises as a result of communicators’ reaction to actions of their opponents. It was traced in the cases of “Euro-plates” (massive importation into Ukraine of not-cleared cars with European license plates) and “Night on Bankova” [the street where the Presidential Office is located] (demands of civic activists for investigation of the allegedly political murder). The first case demonstrates a self-organized non-political platform of owners of such cars, which without the support of any recognizable politician managed to effectively protect their economic interests through communication of their idea to the masses. The second case suggests that due to the use of moderate and non-violent methods of communication and action by civil activists, as well as the high authority and recognizability of communicators, their ideas are attractive: the public accepts them and the authorities demonstrate readiness for the dialogue. It works much better than pushing people to radical actions, as in the case of monotony of street protests. In both cases described above in the context of alertness, a minority conversion takes place, where the discursive impact of the self-organized group is being spread to a broader public. Due to reassessment of the values this effect can potentially be used by interest groups to achieve their political goals and mobilize groups of supporters.

Conclusion

The above described effects can be used to distract public attention, to change (increase or decrease) the level of protest potential, to push people towards impulsive actions, to impose contradictory ideas or to stimulate the society to rethink values – both in a positive or negative way. These effects can be utilized by interest groups to draft the agenda and establish domination of their own discourse in the public sphere.

Thus, the actions to be taken by governmental decision makers who want to deal with negative consequences of such effects are: (1) engaging in the dialogue with the society, (2) responding to the mobilization of large groups of people with policy actions, (3) drawing attention to the importance of human rights (and actually pursuing this policy on the state level instead of only declaring it). One of the major activities here is monitoring aimed at a timely detection of dangerous trends and handling communication in a proper way.

Further research in this direction could be focused on assessing the impact of psychological effects on various target groups in the society in the short- and long-term perspective.

References

- Fairclough, Norman, 1992. “Discourse and social change”, Cambridge Polit Press, 272 p.

- Iarovyi Dmytro, 2019. Psychological practices of civil confrontation in social media. Dissertation, Institute for Social and Political Psychology, National Academy of Educational Sciences of Ukraine, Kyiv.

- Westcott, Nicholas, 2008. “Digital diplomacy: The impact of the Internet on International relations”, Research Report of Oxford Internet Institute, 16, 20 pages.

- Whiting, Anita; and David Lindsey Williams, 2013. “Why people use social media: a uses and gratifications approach”, Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 14(4), 362-36

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in policy briefs and other publications are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect those of the FREE Network and its research institutes.

Are Natural Resources Good or Bad for Development?

Natural resources development undoubtedly plays an important role in the economies of many countries. Whether their contribution to development is positive or negative is, however, a contested and difficult question. Arguably, countries like Australia, Botswana, and Norway have gained enormously over long periods from sustained natural resources development. Others, such as Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Russia, have achieved significant economic growth through natural resources development but perhaps at the expense of institutional progress. In contrast, in some countries—such as Angola and Sierra Leone—natural resources development has been at the heart of violent conflicts, with devastating consequences for society. With many developing countries being highly resource-dependent, a deeper understanding of the sources of success and the risks associated with natural resources development is highly relevant. This brief reviews the main issues and points to key policy challenges for transforming resource rents from natural resources development into a driver rather than a detriment to overall development.

Is it good for a country to be rich in natural resources? Superficially, the answer to this question would obviously seem to be “yes”. How could it ever be negative to have something in addition to labor and produced capital? How could it be negative to have something valuable “for free”? Yet, the answer is far from that simple and one can relatively quickly come up with counterarguments: “Having natural resources takes away incentives to develop other areas of the economy which are potentially more important for long-run growth”; “Natural resource-income can cause corruption or be a source of conflict”, etc.

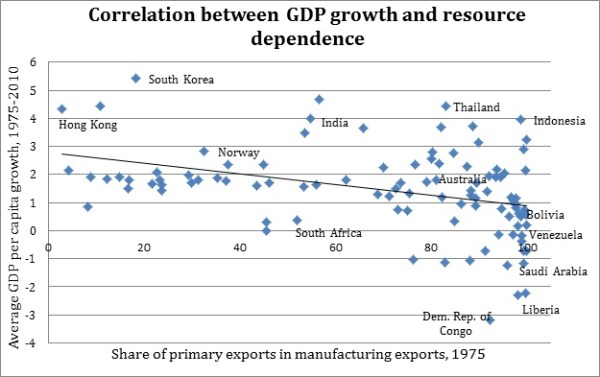

Looking at some of the starkest cases, the “benefits” of resources can indeed be questioned. Take the Democratic Republic of Congo for example. It is the world’s largest producer of cobalt (49% of the world’s production in 2009) and of industrial diamonds (30%). It is also a large producer of gemstone diamonds (6%), it has around 2/3 of the world’s deposits of coltan and significant deposits of copper and tin. At the same time, it has the world’s worst growth rate and the 8th lowest GDP per capita over the last 40 years.[1] The picture for Sierra Leone and Liberia is very similar – they possess immense natural wealth, yet they are found among the worst performers both in terms of economic growth and GDP per capita. While the experiences of countries such as Bolivia and Venezuela are not as extreme their resource wealth in terms of natural gas and oil, respectively, seems to have brought serious problems in terms of low growth, increased inequality and corruption. When one, on top of this, adds that some of the world’s fastest-growing economies over the past decades – such as Hong Kong, South Korea and Singapore – have no natural wealth the picture that emerges is that resources seem to be negative for development.

These are not isolated examples. By now, it is a well-established fact that there is a robust negative relationship between a country’s share of primary exports in GDP and its subsequent economic growth. This relationship, first established in the seminal paper by Sachs & Warner (1995) is the basis for what is often referred to as the resource curse, that is, the idea that resource dependence undermines long-run economic performance.[2]

Based on the World Development Indicators database (World Bank). Primary exports consist of agricultural raw materials exports, fuel exports, ores and metals, and food exports.

At the same time, there are numerous countries that provide counterexamples to this idea. Being the second largest exporter of natural gas and the fifth largest of oil, Norway is one of the richest world economies. Botswana produces 29% of the world’s gemstone diamonds and has been one of the fastest-growing countries over the last 40 years. Australia, Chile, and Malaysia are other examples of countries that have performed well, not just despite their resource wealth, but, to a large extent, due to it.

Given these examples the relevant question becomes not “Are resources good or bad for development?” but rather “Under what circumstances are resources good and when are they bad for development?. As Rick van der Ploeg (2011) puts it in a recent overview: “the interesting question is why some resource-rich economies [.] are successful while others [.] perform badly despite their immense natural wealth”. To begin to answer this question it is useful to first review some of the many theoretical explanations that have been suggested and to see what empirical support they have received. Clearly, our overview is far from complete but we think it gives a fair picture of how we have arrived at our current stage of knowledge.[3]

Theories and Evidence

The most well-known economic explanation of the resources curse suggests that a resource windfall generates additional wealth, which raises the prices of non-tradable goods, such as services. This, in turn, leads to real exchange rate appreciation and higher wages in the service sector. The resulting reallocation of capital and labor to the non-tradable sector and to the resource sector causes the manufacturing sector to contract (so-called “de-industrialization”). This mechanism is usually referred to as “Dutch disease” due to the real exchange rate appreciation and decrease in manufacturing exports observed in the Netherlands following the discovery of North Sea gas in the late 1950s. Of course, the contraction of the manufacturing sector is not necessarily harmful per se, but if manufacturing has a higher impact on human capital development, product quality improvements and on the development of new products, this development lowers long-run growth.[4] Other theories have focused on the problems related to the increased volatility that comes with high resource dependence. In particular, it has been suggested that irreversible and long-term investments such as education decrease as volatility goes up. If human capital accumulation is important for long-run growth this is yet another potential problem of resource wealth.

The empirical support for the Dutch disease and related mechanisms is mixed. Some authors find that a resource boom causes a decline in manufacturing exports and an expansion of the service sector (e.g. Harding and Venables (2010)), others do not (e.g. Sala-i-Martin and Subramanian (2003)). But even the studies that do find evidence of the Dutch disease mechanism, usually do not analyze its effect on the growth rates. In principle, Dutch disease could be at work without this hurting growth. Another problem is that the Dutch disease theory suggests that natural resources are equally bad for development across countries. This means that the theories cannot account for the great heterogeneity of observed outcomes, that is, they cannot explain why some countries fail and others succeed at a given level of resource dependence. The same goes for the possibility that natural resources create disincentives for education. Gylfason 2001, Stijns (2006) and Suslova and Volchkova (2007) find evidence of lower human capital investment in resource-rich countries but the theory cannot explain differences across (equally) resource-rich countries.

As a result, greater attention has been devoted to the political-economic explanations of the resource curse. The main idea in recent work is that the impact of resources on development is heavily dependent on the institutional environment. If the institutions provide good protection of property rights and are favourable to productive and entrepreneurial activities, natural resources are likely to benefit the economy by being a source of income, new investment opportunities, and of potential positive spillovers to the rest of the economy. However, if property rights are insecure and institutions are “grabber-friendly”, the resource windfall instead gives rise to rent-seeking, corruption and conflict, which have a negative effect on the country’s development and growth. In short, resources have different effects depending on the institutional environment. If institutions are good enough resources have a positive effect on economic outcomes, if institutions are bad, so are resources for development.

Mehlum, Moene and Torvik (2006) develop a theoretical model for this effect and also find empirical support for the idea. In resource-rich countries with bad institutions incentives become geared towards “grabbing resource rents” while in countries where institutions render such activities difficult resources contribute positively to growth. Boschini, Pettersson and Roine (2007) provide a similar explanation but also stress the importance of the type of resources that dominate. They show that if a country’s institutions are bad, “appropriable” resources (i.e., resources that are more valuable, more concentrated geographically, easier to transport etc. – such as gold or diamonds) are more “dangerous” for economic growth. The effect is reversed for good institutions – gold and diamonds do more good than less appropriable resources. In turn, better institutions are more important in avoiding the resource curse with precious metals and diamonds than with mineral production. The following graph illustrates their result by showing the marginal effects of different resources on growth for varying institutional quality. Distinguishing the growth contribution of mineral production in countries with good institutions with the effect in countries with bad institutions, the left panel shows a positive effect in the former and a negative one in the latter case. The right-hand panel illustrates the corresponding, steeper effects when isolating only precious metals and diamond production.

Even if these papers provide important insights and allow for the possibility of similar resource endowments having variable effects depending on the institutional setting, two major problems still remain. First, the measures of “institutional quality” are broad averages of institutional outcomes (rather than rules).[5] Even if Boschini et al. (2007), and in particular Boschini, Pettersson and Roine (2011) test the robustness of the interaction result using alternative institutional measures (including the Polity IV measure of the degree of democracy) it remains an important issue to understand more precisely which aspects of institutions that matter. An attempt at studying a particular aspect of this question is the paper by Andersen and Aslaksen (2008), which shows that presidential democracies are subject to the resource curse, while it is not present in parliamentary democracies. They argue that this result is due to higher accountability and better representation of the parliamentary regimes.

A second remaining issue is that even if one concludes that the impact of natural resources differs across institutional environments it is an obvious possibility that natural resources have an impact on the chosen policies and institutional arrangements. For example, access to resource rents may provide additional incentives for the current ruler to stay in power and to block institutional reforms that threaten his power, such as democratization. In a well-known paper with the catchy title “Does oil hinder democracy?” Ross (2001) uses pooled cross-country data to establish a negative correlation between resource dependence and democracy.

However, one needs to be careful in distinguishing such a correlation from a causal effect. There are at least two issues that can affect the interpretation: First, there could be an omitted variable bias, that is, the natural resource dependence and institutional environment can be influenced by an unobserved country-specific variable, such as historically given institutions (which in turn could be the result of unobserved effects of resources in previous periods), culture, etc. For the same reason, cross-country comparisons may also be misleading. One way of dealing with this problem is to use fixed-effect panel regressions to eliminate the effect of the country-specific unobserved characteristics. This approach produces mixed empirical results: in the analysis of Haber and Menaldo (2011) the effect of resources on democracy disappears, while Aslaksen (2010) and Andersen and Ross (2011) find support for a political resource curse.

Second, the measures of natural resource wealth may be endogenous to institutions and, in particular, its level of democracy. For example, the level of oil production and even the efforts put into oil discovery can be affected by the decisions of (and constraints on) those in power. Thereby one would need to find instrumental variables that influence the level of democracy only through the resource measures.[6] Tsui (2011) investigates the causal relationship between democracy and resources by looking at the impact of oil discovery event(s) on a cross-country sample. His identification strategy is based on using the exogenous variation in oil endowments (an estimate of the total amount of oil initially in place) to instrument for the amount of total discovered oil to date. The idea is that, while the amount of oil discovered could well be influenced by the institutional environment, the size of the oil endowment is determined only by nature. Tsui’s findings also support the political resource curse story.

There are also numerous studies about the effect of resources on particular institutional aspects and policies. For example, Beck and Laeven (2006) find that resource wealth delayed reform in Eastern Europe and the CIS, Desai, Olofsgård and Yousef (2009) point to natural resource income as central for the possibilities of autocratic governments to remain in power through buying support, Egorov et. al. (2009) show that there is fewer media freedom in oil-rich economies, with the effect being the strongest for the autocratic regimes. Andersen and Aslaksen (2011) find that natural resource wealth only affects leadership duration in non-democratic regimes. Moreover, in these countries, less appropriable resources extend the term in power (in line with the ruler incentive argument above), while more appropriable resources, such as diamonds, shorten political survival (perhaps, due to increased competition for power). Several papers show that in a bad institutional environment natural resources increase corruption (e.g., Bhattacharyya and Hodler (2010) or Vincente (2010)), and reduce corporate transparency (Durnev and Guriev (2011)).

Implications for Policy

Overall the literature points to potential economic as well as political problems connected to natural resources. Even if some issues remain contested it seems clear that many of the economic problems are solvable with appropriate policy measures and in general that natural resources can have positive effects on economic development given the right institutional setting. However, it seems equally clear that natural resource wealth, especially in initially weak institutional settings, tends to delay diversification and reforms, and also increases incentives to engage in various types of rent-seeking. In autocratic settings, resource incomes can also be used by the elite to strengthen their hold on power.

Successful examples of managing resource wealth, such as the establishment of sovereign wealth funds that can both reduce the volatility and create transparency and also smooth the use of resource incomes over time, are not always optimal or easily implementable. Using the money for large investments could be perfectly legitimate and consumption should be skewed toward the present in a capital-scarce developing setting (as shown by van der Ploeg and Venables, 2011). But no matter what we think we know about the optimal policy it still has to be implemented and if the institutional setting is weak the problems are very real. This is just because of potentially corrupt governments but also due to the difficulty to make credible commitments even for perfectly benevolent politicians (see e.g. Desai, Olofgård and Yousef, 2009).

Many political leaders in resource-rich countries have pointed to the hopelessness of their situation and have expressed a wish to rather be without their natural wealth. Such conclusions are unnecessarily pessimistic. Even if it is true that the policy implications from the literature more or less boil down to a catch-22 combination of 1) “Resources are bad (only) if you have poor institutions, so make sure you develop good institutions if you have resource wealth” and 2) “Natural resources have a tendency to impede good institutional development”, there are possibilities. Some countries have succeeded in using their resource wealth to develop and arguably strengthen their institutions. Even if it is often noted that Botswana had relatively good institutions already at the time of independence, it was still a poor country with no democratic history facing the challenge of developing a country more or less from scratch. And at the time of independence, they also discovered and started mining diamonds which have since been an important source both of growth and government revenue. This development has to a large part been due to good, prudent policy.

There is nothing inevitable about the adverse effects of natural resources but resource-rich developing countries must face the challenges that come with having such wealth and use it wisely. The first step is surely to understand the potential problems and to be explicit and transparent about how one intends to deal with them.

References

- Andersen, J. J. and Aslaksen, S., 2008. “Constitutions and the resource curse.” Journal of Development Economics, Volume 87, Issue 2.

- Andersen, J. J. and Aslaksen, S., 2011. “Oil and political survival.” mimeo.

- Andersen, J. J. and Ross, M., 2011, “Making the Resource Curse Disappear: A re-examination of Haber and Menaldo’s: “Do Natural Resources Fuel Authoritarianism?”.” mimeo.

- Aslaksen, S., 2010. “Oil and Democracy – More than a Cross-Country Correlation?,” Journal of Peace Research, vol. 47(4).

- Beck, T., and Laeven, L., 2006. “Institution Building and Growth in Transition Economies.” CEPR Discussion Paper 5718, Centre for Economic Policy Research:London.

- Bhattacharyya, S., and Hodler, R., 2010. “Natural resources, democracy and corruption” European Economic Review, Elsevier, vol. 54(4).

- Boschini, A.D., Pettersson, J. and Roine, J., 2007. “Resource curse or not: a question of appropriability” Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 109.

- Boschini, A.D., Pettersson, J. and Roine, J., 2011. “Unbundling the resource curse” mimeo.

- David, P. A., and Wright, G.. 1997. “The Genesis of American Resource Abundance” Industrial and Corporate Change 6.

- Desai, R. M., Olofsgård, A. and Yousef, T., 2009. “The Logic of Authoritarian Bargains” Economics & Politics, Vol. 21, Issue 1.

- Durnev, A. and Guriev, S. M., 2011. ”Expropriation Risk and Firm Growth: A Corporate Transparency Channel.”, mimeo

- Egorov, G., Guriev, S. M. and Sonin, K., 2009. “Why Resource-Poor Dictators Allow Freer Media: A Theory and Evidence from Panel Data.” American Political Science Review, Vol. 103, No. 4.

- Gylfason, T., 2001. “Nature, Power, and Growth” Scottish Journal of Political Economy, Scottish Economic Society, vol. 48(5).

- Gylfason, T., Herbertsson, T. T., and Zoega, G., 1999. “A mixed blessing” Macroeconomic Dynamics, 3.

- Findlay, R. and Lundahl M., 1999. “Resource-Led Growth: A Long-Term Perspective.” Helsinki: World Institute for Development Economics Research.

- Frankel, J. A., 2010 “The Natural Resource Curse: A Survey.” HKS Working Paper No. RWP10-005.

- Haber, S. H. and Menaldo, V. A., 2011. “Do Natural Resources Fuel Authoritarianism? A Reappraisal of the Resource Curse.” American Political Science Review, Vol. 105, No. 1.

- Harding, T. and Venables, A.J., 2011. “Exports, imports and foreign exchange windfalls.” mimeo.

- Hausmann R., Hwang J. and Rodrik, D., 2007. “What you export matters.” Journal of Economic Growth, Springer, vol. 12(1).

- Leite, C. A. and Weidmann, J., 1999. “Does Mother Nature Corrupt? Natural Resources, Corruption, and Economic Growth.” IMF Working Paper No. 99/85.

- Mehlum, H., Moene, K. and Torvik, R., 2006. ”Institutions and the resource curse.” Economic Journal, 116.

- Montague, D., 2002. “Stolen Goods: Coltan and Conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo.” SAISReview – Volume 22, Number 1, Winter-Spring, pp. 103-118

- van der Ploeg, F., 2011. “Natural Resources: Curse or Blessing?.” Journal of Economic Literature, American Economic Association, vol. 49(2).

- van der Ploeg, F. and Venables, A. J., 2011. “Harnessing Windfall Revenues: Optimal Policies for Resource-Rich Developing Economies.” Economic Journal, Royal Economic Society, vol. 121(551).

- Ross, M.L., 2001. “Does Oil Hinder Democracy?” World Politics, 53(3).

- Sachs, J. D. and Warner, A. M., 1995. “Natural Resource Abundance and Economic Growth.” NBER Working Papers 5398, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

- Sala-I-Martin, X., Doppelhofer, G. and Miller, R. I., 2004. “Determinants of Long-Term Growth: A Bayesian Averaging of Classical Estimates (BACE) Approach.” American Economic Review, American Economic Association, vol. 94(4).

- Sala-I-Martin, X., and Subramanian, A., 2003. “Addressing the Natural Resource Curse: An Illustration from Nigeria.” NBER Working Paper 9804.

- Stijns, J.-P., 2006. “Natural resource abundance and human capital accumulation.” World Development, Elsevier, vol. 34(6).

- Suslova, E. and Volchkova, N., 2007. “Human Capital, Industrial Growth and Resource Curse.” Working Papers WP13_2007_11, Laboratory for Macroeconomic Analysis, HSE.

- Torvik, R., 2009. “Why do some resource-abundant countries succeed while others do not?”, Oxford Review of Economic Policy, vol. 25(2).

- Tsui, K. K., 2011. “More Oil, Less Democracy: Evidence from Worldwide Crude Oil Discoveries.” The Economic Journal, 121.

- Vincente, P., 2010. “Does Oil Corrupt? Evidence from a Natural Experiment in West Africa,” Journal of Development Economics, 92(1).

- Wright, G., 1990. “The Origins of American Industrial Success, 1879-1940.” American Economic Review 80.

Footnotes

[1] Based on World Development Indicators database (World Bank).

[2] Its robustness has been confirmed in, for example, Gylfason, Herbertsson and Zoega (1999), Leite and Weidmann (1999), Sachs and Warner (2001) and Sala-i-Martin and Subramanian (2003). Doppelhoefer, Miller and Sala-i-Martin (2004) find that the negative relation between the fraction of primary exports in total exports and growth is one of 11 variables which is robust when estimates are constructed as weighted averages of basically every possible combination of included variables.

[3] The interested reader should consult more extensive overviews such as Torvik (2009), Frankel (2010) or van der Ploeg (2011).

[4] This assumption has been criticized by, for example, Wright (1990), David and Wright (1997), and Findlay and Lundahl (1999) who all point to historical examples where resource extraction has been a driver for the development of new technology. On the other hand others, e.g. Hausmann, Hwang and Rodrik (2007), provide evidence that export product sophistication predicts higher growth.

[5] The distinction between using institutional outcomes rather than institutional rules has been much debated in the literature on the importance of institutions in general. It is, for example, possible for a dictator to choose to enforce good property rights protection even if this is something typically associated with democracy.

[6] The studies by Boschini, Pettersson and Roine (2007) and (2011) also use instrumental variables to try to account for the potential endogeneity problems. The results are in line with the OLS results but instruments are weak in this setting.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in policy briefs and other publications are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect those of the FREE Network and its research institutes.