Tag: family benefits

“Active Parent”: Addressing Labor Market Disadvantages of Mothers in Poland

In 2023 only one out of four children aged 0-3 years was covered by the Polish system of formal childcare. Traditional social norms with regard to provision of childcare at home, together with high costs of existing formal and informal childcare arrangements constitute important constraints with regard to labor market participation among mothers with the youngest children. While labor market activity rate among women aged 25-49 years stands at 84 percent overall, it is more than 20 percentage points lower for mothers with children aged 1-3 years. In this policy brief we provide an overview and an evaluation of “Active parent”, a recently introduced policy aimed at supporting earlier return to work after birth among mothers in Poland. We argue that the success of the program will be strongly determined by the extent to which it manages to stimulate growth of high-quality formal childcare for those aged 0-3 in the next few years.

Gender Gaps in Employment and Childcare in Poland

The average labor market activity rate among women aged 25-49 in Poland stands at 84 percent, which is slightly above the EU average (by 2 p.p.; see Figure 1). The rate, however, differs substantially by age group, and even more by the number and age of children. For childless women just below 30 years, the activity rate almost exactly matches the rate for men (88 percent vs 90 percent). However, among women with children, and especially among those with the youngest child being between 1 and 3 years old, this number drops to 62 percent. For fathers with such children, the activity rate however stands at 98 percent. Women gradually return to work when the youngest child is growing up – 3 out of 4 of those with a child aged 4 to 6 years are active in the labor market, and this share grows to 84 percent for mothers of teenagers (aged 13-14 years). At the same time women in Poland are much less likely to work part-time than women in the EU on average (7 vs. 28 percent, respectively; Eurostat, 2021). Rates of part-time employment are higher if women have more and younger children, though not by much (11 percent for mothers of 3+ children, 10 percent when a child is up to 3 years old; PEI, 2022).

While in most Polish households with children both parents are working for pay, traditional gender norms still largely prevail with respect to providing childcare or handling household duties. According to a survey conducted by the Polish Economic Institute (PEI), in only 18 percent of double-earner families do both parents take care of a child to the same extent (Polish Economic Institute 2022). For 68 percent of such families, it is the mother who provides most care. In only 1 in 10 families the father is the main care provider.

Figure 1. Labor market activity rates in Poland in 2022

Source: Authors’ compilation based on: PEI, 2022; Eurostat.

Traditional attitudes towards childcare responsibility are clearly visible in the actual gender split of parental leave in Poland. Despite the introduction of a non-transferable 9-week long parental leave dedicated to fathers (out of the total of 41 weeks of parental leave) on top of a two-week paternity leave, the division of care duties for the youngest children has essentially remained unaffected. While 377 000 mothers claimed parental leave benefits in 2021, only 4 000 fathers decided to stay at home with their child (Social Insurance Institute, 2021). Besides, many fathers still do not exercise their right to the fortnight of the paternity leave. According to the PEI survey conducted among parents of children aged 1-9 years, 41 percent of fathers reported virtually no work gap after the birth of their child and further 43 percent acknowledged only a short break from work (up to 14 days). On the other hand, 85 percent of mothers took a work break after childbirth of more than 8 months. For 40 percent it lasted between 12-18 months and for 28 percent the separation from work exceeded one and a half years.

Evaluating the Consequences of the “Active Parent” Program

To address the resulting disadvantages for mothers on the labor market the current Polish government introduced a program called “Active parent” in October 2024. The program is targeted at parents of children aged 12 to 35 months and consists of 3 options. The highest benefits in the program amounting to 350 EUR per month, are granted within the “Active at work” option to households in which parents are active on the labor market. For couples, the minimum work requirement is half-time work for each parent, while lone parents are required to work full-time. The same monthly amount can be granted if the child is enrolled in institutionalized childcare (“Active in nursery” option), though in this case the benefit does not exceed the cost of the nursery. This option covers both formal public or private nursery as well as semi-formal care provided in “kids clubs”. Finally, in case the child stays at home with a non-working parent (“Active at home” option), the family receives 115 EUR per month.

The main objective of the program is to increase the number of women returning to work after the period of maternity and parental leave (which in Poland cover the first 12 months of a newborn), before the child becomes eligible for kindergarten (where a place for each child aged 3 to 6 years is to be guaranteed by the local government). It is worth noting that after exhausting the parental leave, Polish parents are entitled to up to 3 years of childcare leave. Though this is unpaid, many parents, once again almost entirely mothers, opt for staying at home, often due to the lack of alternative forms of childcare. For children under the age of 3, formal childcare is highly limited. In 2023, nursery places were available only to one out of four children aged 0-3 years (CSO Poland). Additionally, these places are unevenly accessible throughout the country – in 2023 formal childcare for the youngest kids (public or private) did not exist in as many as 45 percent of Polish municipalities (CSO Poland). At the same time, while family help with childcare in Poland is still provided on a massive scale, it is limited only to those who have parents or other family members living close by, already in retirement and without other caring obligations (e.g. for older generations).

Within the new program parents who receive the “Active at work” benefit have complete discretion of how to use these funds. Many may choose to send the child to a formal childcare institution, but the lawmakers also expect a surge in undertaking formal contracts with grandparents or other relatives – including those already in retirement. There’s an additional benefit embedded in this particular solution, namely social security contributions resulting from contracts concluded with “a carer” (regardless of if it is a third person or a family member) which are covered by the state. These contributions are added to the carer’s pension funds and translate into higher retirement benefits – with regular recalculations of pension funds among those already retired and higher expected pension benefits for those still below retirement age.

A recent policy report (Myck, Krol and Oczkowska, 2024), evaluated the impact of the “Active parent” program using the microsimulation model SIMPL. The analysis (based on the Polish Household Budget Survey from 2021) focused on the estimation of the expected costs of the program to the public budget and the distribution of financial gains among households. We find that families eligible to receive support, i.e. those with children aged 12-35 months, are concentrated in the upper half of the income distribution (12.6 percent among the richest households and only 5.4 percent living in the poorest households). Thus, taking the observed work and childcare use patterns from the data we find that the average net gains related to the entire “Active parent” program are also concentrated among the richer households (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Average net monthly gain from the “Active parent” program, assuming no change in parental behavior in reaction to the roll-out of the program

Source: Authors’ calculation with SIMPL microsimulation model based on the Polish Household Budget Survey 2021 data, indexed to 2024. Note: Introduction of the new program automatically withdrew the existing support targeted at families with children in the respective age range: “Family Childcare Fund” of 115 EUR/month for families with the second or next child aged 12-35 months and the co-payment for nursery up to 90 EUR/month. 1 EUR = 4.3 PLN.

Households from the highest income decile group on average gain 220 EUR per month, while those from the poorest income group receive 170 EUR per month. In relative terms, these gains correspond on average to as much as 17 percent of their income, while for the former group the gains do not exceed 4 percent of their income. When disaggregating by the three options of the program, eligible households from the bottom part of the distribution receive much higher gains from the “Active in nursery” or “Active at home” options, as these households are much less likely to have both parents working.

Clearly, some parents may adjust their work and childcare choices in reaction to the introduction of the program, which, in fact, is one of its key objectives. If a family decides to take up work or send their child to a nursery, they become eligible for higher support. Rather than receiving 115 EUR from the “Active at home” option, they become eligible for up to 350 EUR under the other alternative options. In almost 200 000 out of the overall 550 000 families with an age-eligible child, one of the parents (usually the mother) is observed to be out of work. Using this, we estimate the likelihood of taking up work among these non-working mothers and conditional on the expected probabilities of employment we assigned additional families to the two more generous options of the program – either to “Active at work” (those with highest work probability) or to “Active in nursery” (those with lowest work probability). This allows us to evaluate potential changes in the cost and distributional implications of the program under different scenarios. Table 1 presents a set of “gross” and “net” costs of selected combinations of parental reactions. The “gross” costs correspond to the total expenditure of the “Active parent” program, while the “net” costs account first for the withdrawal of previous policies (see note to Figure 2), and second for the budget gains related to taxes and social insurance contributions paid by the parents who are simulated to take up work.

Table 1. “Active parent”: aggregate costs to the public budget under different assumptions concerning work and childcare adjustments among parents

Source: see Figure 2.

Assuming no change in parental behavior (0 percent increase in work and 0 percent increase in enrollment in nursery), the total, “gross” cost of the program for the public finances amounts to 1.72 bn EUR, on average, annually. Savings related to the withdrawal of existing policies lower this cost by 0.5 bn EUR. Any modelled increase in nursery enrollment (with no concurrent reaction in the labor market) means an increase in both the “gross” and the “net” costs, while on the other hand an increase in labor market participation of the non-working parent (when nursery enrollment is held constant) expands the “gross” costs but reduces the “net” costs due to higher taxes and contributions paid in relation to simulated additional earnings.

The final distributional household effects of the program will depend on the actual reactions among parents. However, according to our simulations, the families who are most likely to either increase employment of the second parent or sign up their child for a nursery, and, thus, gain from the “Active at work” or “Active in nursery” options, are those currently located in the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th income decile group in the distribution (for more details see: Myck, Krol and Oczkowska, 2024).

Conclusion

The main objective behind the introduction of the new “Active parent” scheme is to increase the labor market participation among mothers with the youngest children. As the program aims to facilitate balancing professional careers with family life among parents, it can also be expected to contribute to increases in the fertility rate, which has recently fallen in Poland from 1.45 in 2017 to 1.16 in 2023 (CSO Poland).

The success of the “Active parent” program should be evaluated with respect to three important indicators:

- the resulting increase in the number of mothers who have taken up work,

- the increase in the number of children registered for nurseries,

- and, related to the latter – the increase in the availability of childcare places in different Polish municipalities.

It is worth noting that the “Active parent” program was introduced in parallel with the prior “Toddler +” program that aimed at creating new childcare institutions and more places in the existing ones in 2022-2029 in Poland. Central funding was distributed to reach these goals among local governments and private care providers. However, a 2024 midterm audit of the “Toddler +” program demonstrated the progress to be “insufficient and lagging” (Supreme Audit Office Poland, 2024). The “Active parent” program will play an important role in providing additional stimulus to the provision of new childcare places for the youngest kids in different Polish regions, which should help the “Toddler +” program to finally gather momentum. In the medium and long run, the development of high-quality formal childcare for children below 3 years will be a crucial determinant of an increase in early return to work among mothers.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to acknowledge the support of the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) under the FROGEE project. The views presented in the Policy Brief reflect the opinions of the Authors and do not necessarily overlap with the position of the FREE Network or Sida.

References

- CSO (Central Statistical Office) Poland. Local Data Bank: Formal childcare: rate of children, number of places; Fertility rates.

- Eurostat. Labour force participation and part-time work.

- Myck, M., Krol, A., Oczkowska, M., (2024). “Active at work, in a nursery, or at home: Financial consequences of the “Active parent” program”, CenEA Report (in Polish).

- PEI (Polish Economic Institute). (2022). “Work vs. home. Parental challenges and their consequences”, PEI Report (in Polish).

- Social Insurance Institute. (2021). Number of parental leave benefits.

- Supreme Audit Office Poland. (2024). “Development of childcare system, including administration of the program “Toddler+”, Post-control results report (in Polish).

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in policy briefs and other publications are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect those of the FREE Network and its research institutes.

From Partial to Full Universality: The Family 500+ Programme in Poland and Its Labour Supply Implications

The implementation of the ‘Family 500+’ programme in April 2016 represented a significant shift in public support for families with children in Poland. The programme guaranteed 500 PLN/month (approx. 120 euros) for each second and subsequent child in the family and the same amount for the first child in families with incomes below a specified threshold. As of July 2019, the benefit has been made fully universal for all children aged 0-17, an extension which nearly doubled its total cost and benefited primarily middle and higher income households. We examine the labour market implications of both the initial design and its recent fully universal version. Using the discrete choice labour supply model, we show that the initial Family 500+ benefits generated strong labour supply disincentives and were expected to result in the withdrawal of between 160-200 thousand women from the labour market. The recent removal of the means test is likely to nullify this negative effect, leading to an approximately neutral impact on labour supply. We argue that when spending over 4% of GDP on families with children, it should be possible to design a more comprehensive system of support, which would be more effective in reaching the joint objectives of low child poverty and high female employment combined with higher fertility rates.

Introduction

Following the 2015 parliamentary elections in Poland the ruling Law and Justice Party was quick to fulfill their campaign promise of implementing a generous quasi-universal family support programme. In April 2016, all families began receiving PLN 500 (approx. 120 euros) per month for each second and subsequent child, while households that passed an income means test were granted the same amount for their first or only child. At a cost of nearly PLN 22 billion (5.2 billion euros, approx. 1.1% of GDP) per year, the Family 500+ benefit became the flagship reform of the Law and Justice government’s first term.

With new elections approaching in October this year, the government announced a significant expansion of the programme in May, which made it fully universal. The extended programme is nearly twice as expensive with an additional cost of PLN 18.3 billion (4.3 billion euros) per year, valuing the whole package at over 2% of GDP. This takes the total value of financial support for families with children, including family benefits and child-related tax breaks, to 4% of GDP and it means that as far as family support is concerned, the ruling party has brought Poland from one of the lowest-spending countries in the EU to one of the highest over the course of 4 years.

The initial design of the benefit had a significant impact on childhood poverty in Poland, with an absolute and relative decrease from 9.0 to 4.7 percent and 20.6 to 15.3 percent respectively between 2015 and 2017 (GUS, 2017). While a more targeted design could have made a far greater impact, these changes still reflect a significant improvement in the material situation of families with children. The policy may have also had a modest upward effect on fertility rates in the first years following its implementation, although this is difficult to assess given the parallel roll out of several other fertility-oriented policies and other changes which could have played a role in family decisions. Simultaneously, as argued in the ex-ante analysis by Myck (2016) and ex-post analysis by Magda et al. (2018), these positive outcomes came at the cost of reduced female labour market participation. This reduction primarily affected women with both lower levels of education and living outside of large urban areas (Myck and Trzciński, 2019).

The Family 500+ Reform: Design and Distributional Implications

The initial Family 500+ programme directed funds to 2.7 million families in addition to any already existing financial support and has been excluded from other means-tested support instruments. Since families that had a net income of less than PLN 800 per month per person could receive the benefit for the first or only child, the policy had a distinct redistributive element and meant that the bottom half of the income distribution received nearly 60% of the funds. However, the design was characterised by clear labour market disincentive effects, which were particularly strong for second earners and single parents.

In a one-child household (53.3 percent of families with children, GUS, 2016) with the first earner bringing in an income equivalent to 125% of the national minimum wage, the second earner needed only to earn PLN 940 per month in order for the family to cross the means test threshold and stop receiving the Family 500+ benefits. The benefit design is presented in Figure 1 in the form of budget constraints for the first earner (Case A) and the second earner (Case B) in a couple with one child. In the latter case the first earner is assumed to receive earnings equivalent to 125% of the minimum wage. The disincentive effects of the means test are clear in both cases and we can see that for the second earner, the benefit withdrawal comes at a very low income level – far below the national minimum wage of PLN 2100 per month. The “point withdrawal” of the benefit implied that it was enough for the family to marginally exceed the means test threshold for it to completely lose eligibility for the Family 500+ support for the first child.

The expansion of the Family 500+ programme, which came into effect in July 2019, eliminated the means-tested threshold thus making the policy fully universal. It came, however, at the cost of the redistributive character of the programme. Over 32% of the additional expenditure resulting from the universal character of the policy has been passed on to the top quintile of the income distribution and in its new version, the bottom half of households only receive 45 percent of all spending. The expansion of the programme is thus unlikely to further reduce child poverty significantly and – since its beneficiaries are mainly families with middle and high incomes – it is not expected to bring noticeable changes in fertility levels.

Figure 1: Family budget constraints for the first and second earner

Source: Authors’ calculations using the SIMPL microsimulation model.

Partial and Full Universality of the Family 500+ Programme and the Implications on Female Labour Supply

With the use of modelling tools to simulate the labour market response to changes in financial incentives to work, we have updated the initial simulations of Myck (2016) using the latest pre-reform data and examined the simulated labour supply decisions to the expanded fully universal programme, as if it were implemented instead of the initial version of the benefit. The analysis was conducted with data from the 2015 Polish Household Budget Survey, a detailed incomes and expenditure survey conducted annually by the Polish Central Statistical Office.

Table 1: Effects of the initial and the expanded Family 500+ programme on female labour supply

Results of the simulations are presented in Table 1. Simulations were conducted separately for single women, and under two scenarios for women in couples assuming that both partners adjust their behaviour (Model A) and that the labour market position of the male partner is unchanged (Model B). The simulated labour supply response to the initial reform confirms the magnitude of earlier results and suggests an equilibrium effect of 160-200 thousand women leaving the labour force. This is also consistent with results presented by Magda et al. (2018), who found that female labour market participation decreased by approx. 100 thousand women after the policy had been in place for one year.

However, as we can see in the right-hand part of Table 1, the response to a fully universal design – modelled as if it was introduced in 2016 instead of the means-tested version – is essentially neutral. For single mothers the reduction is only about 3000, while for women in couples, the model suggests a small positive reaction under the Model A specification and a small negative one under Model B. In total, the universal design of Family 500+ benefits can be described as labour supply neutral. Since the reaction has been modelled on pre-reform data, and because some women have already withdrawn from the labour market after the introduction of the initial benefit design in 2016, the remaining uncertainty is whether the new set of incentives will motivate these mothers sufficiently to return to work.

Conclusion

The introduction and subsequent expansion, of the Family 500+ programme has substantially increased financial resources of families with children in Poland. The policy rollout of the initial, partially universal programme has seen substantial changes in the level of child poverty in Poland and may have contributed to a modest increase in fertility in the initial years following the introduction of the reform. The means-tested design of the benefit, however, incentivised a significant number of women to leave the labour market. One year after the introduction of the policy approximately 100,000 women were estimated to have left the labour market (Magda et al. 2018), while the equilibrium effect of the policy suggested long-run implications of over 200,000 (Myck, 2016). The updated simulation results using the latest available data suggest slightly lower, though still substantial equilibrium implications of the initial partially universal design of the Family 500+ programme in the range of between 160,000-200,000. However, as we show in our latest analysis, these labour market consequences could be reversed after the expansion of the programme to a fully universal set-up. The simulated effects of the universal design of the programme, which has been in place in Poland since July 2019, modelled as if it was implemented instead of the initial means-tested version, are broadly neutral for female labour supply. The only question is how likely the mothers who left employment in response to the initial policy will return to work given the new set of financial incentives. Considering these positive implications of the fully universal programme, one has to bear in mind that the extended programme, which will cost over PLN 40 bn per year (approx. 2% of GDP), is unlikely to contribute to the other key objectives set by the government, namely reducing child poverty and increasing fertility. Including the Family 500+ programme, the Polish government currently spends about 4% of GDP on direct financial support for families with children. Given the design of the policies which make up this family package, it seems that the joint objectives of higher fertility, reduced poverty and higher female employment could be achieved more effectively under a reformed structure of support that would be better targeted at poorer households, include specific employment incentives, and incorporate support for childcare, early education and long-term care.

Acknowledgements

This brief summarizes the results presented in Myck and Trzciński (2019). The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, Sida, through the FROGEE project. For the full list of acknowledgements see Myck and Trzciński (2019).

References

- Goraus, K. and G. Inchauste (2016), “The Distributional Impact of Taxes and Transfers in Poland”, Policy Research Working Paper 7787, World Bank.

- GUS (2016), “Działania Prorodzinne w Latach 2010-2015”, Główny Urząd Statystyczny – Polish Central Statistical Office, Warsaw.

- GUS (2017), “Zasięg ubóstwa ekonomicznego w Polsce w 2017r.”, Główny Urząd Statystyczny – Polish Central Statistical Office, Warsaw.

- Magda, I., A. Kiełczewska, and N. Brandt (2018), “The Effects of Large Universal Child Benefits on Female Labour Supply”, IZA Discussion Paper No. 11652, IZA-Bonn.

- Myck, M. (2016), “Estimating Labour Supply Response to the Introduction of the Family 500+ Programme”, Working Paper 1/2016, CenEA. Jacobson, L., LaLonde, R. and Sullivan, D. (1993). “Earnings losses of displaced workers”, American Economic Review, 83, pp. 685–709.

- Myck, M. and Trzciński, K. (2019) “From Partial to Full Universality: The Family 500+ Programme in Poland and its Labor Supply Implications”, Ifo DICE report 3 / 2019.

Financial Support for Families with Children and Its Trade-Offs: Balancing Redistribution and Parental Work Incentives

Authors: Michal Myck, Anna Kurowska and Michal Kundera, CenEA.

Reforms of tax-benefit system of financial support for families with children have a broad range of consequences. In particular, they often imply trade-offs between effects on income redistribution and work incentives for first and second earners in the family. Understanding the complexity of the consequences involved in reforming family policy is crucial if the aim is to “kill two birds with one stone” namely to reduce poverty and improve incentives to work. In this brief, we illustrate these complex trade-offs by analyzing several scenarios of reforming financial support for families with children in Poland. We show that it is possible to create incentives for second earners in the family to join the labor force without destroying the work incentives of the first earners. Moreover, the same reform would allocate resources to families with lower incomes, which could result in a direct reduction of child poverty.

Financial support for families with children is an important and integral part of the broad family policy package, the goals of which fall into two basic categories of reducing child poverty and increasing labour market activity of parents (Whiteford and Adema, 2007; Björklund, 2006; Immervoll, et al., 2001). However, the particular policy aimed at one of these objectives may be detrimental to the achievement of other goals. For example, family/child benefits may directly increase family income and thus reduce child poverty. These same benefits could have a negative effect on parental incentives to work, particularly for so-called second earners, usually mothers (see e.g. Kornstad and Thoresen, 2007). However, employment of both parents often turns out to be crucial for a long-term poverty reduction (Whiteford and Adema, 2007).

The trade-offs implied by the different family policy instruments are often poorly understood or treated superficially in the policy debate. The effect of this lack of understanding may result in badly designed policy reactions to identified problems, which in turn may imply that one of the objectives is achieved at the cost of the other, or even that policies work against all of them in a longer perspective.

Using the Polish microsimulation model SIMPL, we simulate modifications of several elements of the Polish tax and benefit system to demonstrate the complex nature of trade-offs between income and employment policy, and within employment policy itself. The underlying assumption of the analysis is that any effective policy that aims at lowering child poverty in the long run ought to realize and address issues of parental labour market activities. Governments should therefore aim at a design of financial support for families to provide assistance to poor households and at the same time strong work incentives for parents.

The Polish system of support for low-income families, Family Benefits, consists primarily of Family Allowance (FA) with supplements. These are means-tested and are available to families with net incomes below 504 PLN (€121) per month and per person. The value of the FA depends on the age of the child and ranges from 68 PLN to 98 PLN (€16.40 to €23.60) per month. For eligible parents this is supplemented by additional means-tested payments to such groups as lone parents, families with more than two children, and those with school-aged children. Eligibility for Family Benefits is assessed with reference to a threshold, which once exceeded makes the family ineligible to claim the benefits. This point withdrawal of benefits implies very high effective marginal tax rates and has significant implications for average effective rates of taxes (see Myck et al., 2013). In addition to Family Benefits, financial support for families is also channelled through the tax system. Tax-splitting (joint taxation) is available to married couples and lone parents, and since 2007 parents can set their tax liabilities against the Child Tax Credit, which is a non-refundable tax credit, the maximum value of which is 1,112.04 PLN (€268) per year for every dependent child.

The starting point for our analysis, and a reference in terms of potential costs of the reform, is the move to tapered withdrawal of Family Benefits (System 1). For this purpose we use the rate of withdrawal at 55%, which is the rate used in a broadly studied in-work support programme in the UK, the Working Families’ Tax Credit (WFTC) in the late 1990s and early 2000s (see, e.g.: Blundell et al., 2000; Brewer et al., 2006; Clark et al., 2002). Application of the taper implies that with an increase of net income of 1 PLN beyond the withdrawal threshold, the total value of benefits is reduced by 0.55 PLN. Such a change would imply greater certainty and predictability of benefit receipt, compared to the current point withdrawal system. However, as it extends the availability of benefits to families who currently no longer qualify for them, it would carry additional costs. We estimate this cost to be in the range of about 1.04 billion PLN (€250mln) per year, an increase in the total value of family benefits by about 14%.

Changes in Family Benefits under System 2 involve simple increases in the values of Family Allowance, which is raised by 20% given the above cost benchmark of 1.04 billion PLN. The final reform to Family Benefits (System 3) combines introduction of the withdrawal taper (at 55%) with a bonus system for two-earner families with the specific aim of providing stronger work incentives for second earners. The bonus consists of an increase in the level of the withdrawal threshold by 50% for families where both parents work compared to the baseline threshold value.

The first reform of Child Tax Credit (System 4) assumes an increase in the value of the CTC by 19.8% (calibrated to cost same 1.04 billion PLN), while the second uses this tax credit instrument to reward two-earner status. In the latter case, double-earner couples are granted an additional value of the credit (92.70 PLN per month). The cost of this reform is again calibrated to the level of other reforms by adjusting the earnings requirement set for both parents to qualify as double-earner couples. This calibrated requirement is 2,324.50 PLN per month and per person, which is equivalent to 176.5% of the minimum wage.

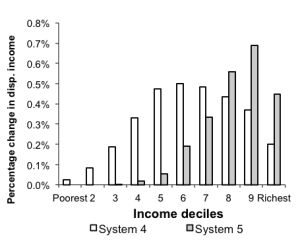

The assumptions underlying the modelled scenarios are very clearly reflected in the (static) distributional effects of the simulated changes. The proportional changes in incomes among families with children by population decile groups resulting from the simulated reforms are demonstrated in Figure 1A for Systems 1-3 and Figure1B for Systems 4-5.

Figure 1. Distributional consequences of modelled reforms: Proportional changes in incomes of families with children by income deciles.

Source: Authors’ calculations using the SIMPL microsimulation model on PHBS 2010 data.

Source: Authors’ calculations using the SIMPL microsimulation model on PHBS 2010 data.

Figures 2 and 3 show how the modelled reforms would affect incentives to work for first and second earners measured as average changes in replacement rates[1] (RRs) by centiles of the baseline distribution of replacement rates for modelled families. The RR for the first earner is the ratio of the family income when neither partners work and the family income when the first earners works full time. The RR for the second earner is the ratio of the family income when only first earners work and the family income when both partners work full time. Lowest values of RRs imply the strongest incentives and highest values reflect the weakest incentives to work. When the difference in RR between the Baseline and a particular System is greater than zero it implies that this System increases incentives to work for a particular earner compared to the Baseline. This approach provides evidence on the trade-off between improving work incentives for those facing strong and weak incentives in the baseline system. The pattern that emerges from Figures 2 and 3 reflects to some extent the distributional effects of the chosen reforms (Figure 1). This is because richer families are usually those with high labour market incomes and thus low RRs (high labour market incentives), while poorer families face weaker incentives given their low actual (or potential) earnings, and thus face higher replacement ratios.

Figure 2. Changes in RRs by baseline work incentives – first earners Source: Authors’ calculations using the SIMPL microsimulation model on PHBS 2010 data.

Notes: Based on a sample of couples with children. System 5 does not change first earner incentives.

Figure 3. Changes in RRs by baseline work incentives – second earners

Source: Authors’ calculations using the SIMPL microsimulation model on PHBS 2010 data.

Notes: Based on a sample of couples with children. System 5 does not change first earner incentives.

Figure 3. Changes in RRs by baseline work incentives – second earners

Source: Authors’ calculations using the SIMPL microsimulation model on PHBS 2010 data.

Notes: Based on a sample of couples with children.

Source: Authors’ calculations using the SIMPL microsimulation model on PHBS 2010 data.

Notes: Based on a sample of couples with children.

Apart from the well-established trade-off between equity and labour market concerns, our paper draws attention to the need to balance out first and second earner work incentives as well as incentives by the degree of existing financial motivation to work.

Reforms at the two extremes of the distributional spectrum, namely an increase in the level of Family Benefits (System 2) and a Child Tax Credit bonus for two-earner couples (System 5), result in very different incentive effects. The former significantly weakens incentives of both first and second earners in couples, while the second, which specifically directs resources at second earners, produces important improvements in incentives to work for second earners. However, these gains focus on the part of the spectrum of the baseline distribution of work incentives where these are already strong. This contrasts with a reform in which a two-earner “bonus” is created as part of Family Benefits (System 3). This system increases the generosity of in-work support for first earners in couples in a similar way to the benchmark reform. At the same time, however, it improves the attractiveness of work for second earners by raising the level of income from which benefits are withdrawn for couples in which both partners are working.

This arrangement balances out the negative influence on second earner incentives of the income effect of making work more financially attractive for first earners, which does not happen under our benchmark scenario (System 1). Moreover, we demonstrate that trying to increase work incentives through higher levels of Child Tax Credit available to families would have a positive effect on the work incentives of a large number of families, in particular on first earners in couples. The flip side of this effect would be some negative incentive effects on second earners, but generally both types of effect would be very low given the assumed cost restriction of the modelled reforms.

Naturally, there is an endless number of ways in which a billion PLN can be spent on families with children. As we argued above, each type of reform will have a complex set of consequences on household incomes and incentives to work for parents. The breakdown of employment pattern in Poland suggests that to increase labour market activity, the family support policy should focus on trying to make work pay for second earners in couples, most of whom are women. As we demonstrated this can be done in such a way as to balance out incentives for first earners and provide strong incentives to those second earners who currently face the weakest incentives to work. At the same time, resources would be directed to families in the lower half of income distribution that could result in direct reduction of child poverty.

▪

References

- Blundell R., A. Duncan, J. McCrae and C. Meghir (2000) The Labour Market Impact of the Working Families’ Tax Credit, Fiscal Studies, vol. 21(1), pp. 75-104.

- Brewer M., A. Duncan, A. Shephard and M.-J. Suarez (2006) “Did Working Families’ Tax Credit Work? The Impact of In-Work Support on Labour Supply in Great Britain”, Labour Economics, vol. 13, pp. 699-720.

- Björklund A. (2006) Does family policy affect fertility? Journal of Population Economics, vol. 19 (1), pp. 3-24.

- Clark T., A. Dilnot, A. Goodman, and M. Myck (2002) Taxes and Transfers, Oxford Review of Economic Policy, vol.18 (2), pp. 187-201.

- Immervoll H., H. Sutherland, K. de Vos (2001) Reducing child poverty in the European Union: the role of child benefits, in: Vleminckx K. and Smeeding T.M. (eds) Child well-being, Child poverty and Child Policy in Modern Nations. What do we know? Revised Edition; The Policy Press: Bristol.

- Kornstad T. and T. O. Thoresen (2007) A Discrete Choice Model for Labor Supply and Child Care, Journal of Population Economics, vol. 20 (4), pp. 781-803.

- Myck, M., A. Kurowska, and M. Kundera (2013) “Financial Support for Families with Children and its Trade-offs: Balancing Redistribution and Parental Work Incentives”, Baltic Journal of Economics, 13(2), 59-84.

- Whiteford P. and W. Adema (2007) What Works Best in Reducing Child Poverty: A Benefit of Work strategy? OECD Social, Employment and Migration Woking Papers, nr 51, OECD, Paris.

[1]For the couples in the subsample we compute three sets of family-level incomes, conditional on employment either of the first earner (who is the person with higher expected earnings in a couple) or of both partners; Y(1,1) for the scenario where both partners are employed (full-time); Y(1,0) for the scenario where the first earner is employed (full-time); Y(0,0) for the scenario where both partners are not employed. This allows us to compute replacement ratios for the first earner (RR1) and the second earner (RR2) for each of the analysed tax and benefit systems (S): RR1(s,j)=Y(s,j)(0,0)/Y(s,j)(1,0) and RR2(s,j)=Y(s,j)(1,0)/Y(s,j)(1,1).