Tag: Natural resources

Russia’s New Strategy in Africa: Big Ambitions, Limited Gains

Russia’s renewed engagement with Africa has expanded rapidly since 2022, as Moscow seeks to counterbalance its growing international isolation. Drawing on trade, diplomatic, and UN voting data, this brief finds that while Russia has intensified relations with a handful of African states, the overall involvement remains limited in scope and depth. Economic ties are concentrated in fragile and politically isolated countries, while indicators of political alignment, such as UN General Assembly voting, suggest declining rather than increasing support. Russia’s new strategy may yield short-term geopolitical leverage but shows little sign of delivering durable economic or political gains.

Since the introduction of Western sanctions in 2014, and especially following its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Russia has intensified its geopolitical and economic engagement across Africa. A previous brief (Berlin, 2024) outlined the main areas of Russian activity and the strategic objectives behind this renewed focus. As discussed there, Russia’s approach stands in sharp contrast to the longer-term strategies of both traditional Western partners and newer actors such as China. Rather than pursuing sustained investment or development-oriented cooperation, Moscow has adopted a realist and opportunistic stance, prioritizing short-term gains while paying little attention to potential side effects such as heightened instability and conflict. This brief examines whether this strategy is yielding tangible results for Russia; specifically, whether it has succeeded in strengthening ties with valuable new partners on the African continent and securing broader diplomatic legitimacy.

Uneven Economic Footprint

Trade statistics show a modest expansion of Russia–Africa trade since 2022, with growth concentrated among a few countries. Egypt shows the strongest increase in its share of Russia’s exports, while other countries with noticeable gains include Ethiopia, Tanzania, Uganda, and Madagascar. Many of these states are resource-rich, supplying Russia with minerals and agricultural goods, ranging from citrus, olives, and cocoa to gold, diamonds, and uranium. Some are former French colonies that harbor various degrees of anti-French or anti-colonial sentiment and, except for Egypt, maintain a degree of distance from Western trade and aid networks. This pattern suggests that Russia’s growing import links are concentrated among commodity-exporting and geopolitically flexible countries, reflecting a pragmatic effort to diversify supply sources rather than the emergence of deep economic partnerships.

Figure 1. Average change in export share to Russia, 2022-2024 vs 2019-2021.

Source: Mirrored trade data from CORISK.The countries showing the strongest increases in imports from Russia since 2022 include Libya in the north; Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, and the Republic of the Congo in the west; and Tanzania, Uganda, Kenya, and Zimbabwe in the east and south. Most of these economies are net-importers of fuel, fertiliser, and grain. In the immediate aftermath of the full-scale invasion, Russia appears to have sought to gain market advantage over Ukrainian exports (and did so in part by capitalising on the Ukrainian port blockade). Several countries have also entered into cooperation in nuclear technology. These are all sectors in which Russia has for a while actively sought to expand its market presence. Arms sales had also been among Russia’s most profitable exports to the continent, until the escalation of the war in Ukraine tied up most of its capacity. Nevertheless, the overall volume of trade with Russia remains modest compared with Africa’s exchanges with other major partners.

Figure 2. Average change in import share from Russia, 2022-2024 vs 2019-2021.

Source: Mirrored trade data from CORISK.

Few of Africa’s most dynamic economies, those experiencing sustained growth and deeper integration into global markets, feature prominently in this trend. Only Ethiopia, Tanzania, and, to some extent, Kenya stand out as moderately growing economies with notable trade expansion toward Russia. This pattern could indicate that Russia’s engagement is driven more by short-term political expediency than by prospects for durable economic cooperation. At the same time, it may also reflect a reactive strategy, with Russia focusing on partners that remain accessible, while wealthier and more stable countries have limited need or willingness to risk established ties with Western markets.

Politics Over Partnership

Diplomatic data reveal a similar pattern. Between 2022 and 2023, Moscow’s state visits to Africa focused heavily on slower-growing or politically isolated countries, including Mali and Sudan. Only Egypt and Ethiopia, both larger economies with diversified external relations, received higher-profile visits and strategic agreements. Participation in the 2023 Russia–Africa Summit in St Petersburg, although broad, with 49 of 54 African countries represented, was lower than at the inaugural summit in Sochi in 2019, with only 17 heads of state compared to 43 in Sochi. Further, these came predominantly from slower-growing or politically isolated countries, including Mali, Burkina Faso, the Central African Republic, the Republic of the Congo, Eritrea, Libya, and Zimbabwe. While larger economies such as Egypt, South Africa, and Senegal also participated at a high level, the overall pattern suggests once more that Russia’s recent outreach has concentrated on politically receptive or less globally integrated states, reflecting both the reluctance of more dynamic economies to risk established ties with Western partners and Moscow’s limited room for maneuver.

In turn, Russia’s military cooperation agreements with African states have increased markedly in recent years. Documented cases include, again, many of the countries already mentioned above, such as the Central African Republic, Mali, Libya, Sudan, Burkina Faso, and Niger.

The combination of arms deals, Wagner-linked security arrangements, and elite-level political support reflects a transactional approach, where immediate influence outweighs sustainable cooperation.

UNGA voting patterns

If Russia’s growing presence were translating into stronger political alignment, one way this would be visible would be in international voting patterns. Yet UN General Assembly data indicate the opposite trend. While several African countries abstained, rather than siding against Russia on the three major resolutions on Ukraine, which has concerned many observers, in general, the average agreement rate of African countries with Russia, historically around 75–80 percent, has fallen to its lowest level since the 1970s.

Figure 3. Average agreement with Russia/USSR in UN resolutions over time

Source: Bailey et al., 2017

Figure 4. Distribution of agreement with Russia/USSR in UN resolutions over time

Source: Bailey et al., 2017. Lighter shades from blue to red to yellow represent more recent voting distributions.

The distribution of votes has become increasingly polarized, with more countries distancing themselves or adopting neutral positions. These patterns suggest that Russia’s efforts to leverage security and diplomatic engagement into broader political loyalty have met limited success. Despite increased activity, Russia’s influence appears confined to a narrow set of partners rather than expanding across the continent.

The Battle Over Hearts and Minds

Foreign presence, whether in the form of military, economic, or diplomatic engagement, can shape public attitudes in complex ways. During the Cold War, for example, development cooperation to Africa was widely used as a tool to project ideological influence and promote alternative institutional models, values, and norms. As the foreign aid paradigm came under critical scrutiny from the 1980s onward, the question of how aid affects attitudes toward donors and development models has become increasingly salient (Andrabi and Das, 2005).

The impact of foreign actors on local perceptions has been explored across various settings. A substantial literature has examined the United States and, to some extent, the USSR as two of the most prominent power actors in the international arena, spanning foreign aid, economic and diplomatic relations, and military involvement (Allen et al., 2020; Vine, 2015). Similarly, Chinese investment and lending have gained popularity in many countries but have also been linked to increased corruption and weakened governance in some contexts (Isaksson & Kotsadam, 2018a, 2018b).

In fragile or politically unstable regions, especially those marked by weak state control, violent conflict, or active competition for power among domestic or international actors, public opinion is particularly vulnerable to external influence. In such contexts, and particularly where Russia is present, disinformation campaigns, anti-Western narratives, and appeals to historical grievances can play a significant role in shaping attitudes and perceptions. Russian propaganda efforts are often focused on delegitimizing Western actors by invoking anti-colonial rhetoric and promoting authoritarian, revisionist alternatives (Lindén, 2023; Akinola & Ogunnubi, 2021). Indeed, information influence remains one of the domains where Russia can achieve the greatest impact at minimal cost. While resource constraints are beginning to limit Moscow’s ability to “buy” influence through trade incentives, arms deals, and other forms of economic cooperation, manipulating audiences on platforms such as X or Facebook through coordinated networks of bots remains inexpensive and effective. A recent study by Cedar reports that RT France (formerly Russia Today) has expanded its following on X by 80 percent and on Facebook by 35 percent since 2022. Ukraine’s military intelligence (HUR) notes that in 2025 RT also began translating content into Portuguese to reach audiences in Mozambique and Angola, and plans to launch programming in Amharic to target viewers in Ethiopia by the end of the year.

Western organizations must do a better job at communicating the benefits of their engagement and the values behind it. In regions saturated with Russian media messaging, proactively engaging local narratives by highlighting successful projects, promoting transparency, and countering misinformation is key to maintaining public goodwill.

Figure 5. Share of African audiences increased as RT’s access in Europe was restricted

Source: Cedar.

Conclusion

Russia’s engagement in Africa is driven less by economic partnership and more by opportunistic, short-term goals: access to strategic resources, military presence, and symbolic legitimacy. While these ties may help Moscow navigate temporary diplomatic isolation, they do not appear to generate lasting political or economic gains for Russia, for the time being.

A pressing question is whether they impact development outcomes for African counterparts, and in what direction. Ongoing work within the FREE NETWORK is now using geolocated data to identify how Russian and Wagner-linked activity shapes donor engagement, local development, and public sentiment across affected regions (see preliminary results in Berlin and Lvovskyi, 2025). The analysis is expected to provide a clearer assessment of whether Russia’s outreach in Africa delivers tangible influence or remains largely symbolic.

References

- Akinola, Akinlolu E., och Olusola Ogunnubi. ”Russo-African Relations and Electoral Democracy: Assessing the Implications of Russia’s Renewed Interest for Africa”. African Security Review, 03 juli 2021. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10246029.2021.1956982

- Allen, Michael A., Michael E. Flynn, Carla Martinez Machain, och Andrew Stravers. ”Outside the Wire: U.S. Military Deployments and Public Opinion in Host States”. American Political Science Review 114, nr 2 (may 2020): 326–41. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055419000868.

- Andrabi, Tahir, Jishnu Das. “In aid we trust: Hearts and minds and the Pakistan earthquake of 2005″. Review of Economics and Statistics, 99 (3), (2017) pp. 371 – 386

- Bailey, Michael A., Anton Strezhnev, and Erik Voeten. “Estimating dynamic state preferences from United Nations voting data.”Journal of Conflict Resolution 61.2 (2017): 430-456.

- Berlin, Maria P., 2024. “Russia in Africa: What the Literature Reveals and Why It Matters”, FREE Policy Brief.

- Berlin, Maria P., and Lev Lvovskyi 2025. “Russia’s Involvement on the African Continent and its Consequences for Development: The Aid Channel”, SITE Working Paper No 64.

- Isaksson, Ann-Sofie, och Andreas Kotsadam. ”Chinese aid and local corruption”. Journal of Public Economics 159 (2018a): 146–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2018.01.002.

- Lindén, Karolina. ”Russia’s Relations with Africa: Small, Military-Oriented and with Destabilising Effects”, 2023.

- Vine, David. 2015. Base Nation: How U.S. Military Bases Abroad Harm America and the World. New York: Metropolitan Books/ Henry Holt.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in policy briefs and other publications are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect those of the FREE Network and its research institutes.

Investing, Producing and Paying Taxes Under Weak Property Rights

Oil majors often choose to operate in countries with weak property rights. This may appear surprising, since the lack of constraints on governments may create incentives to renege on initial promises with firms and renegotiate tax payments once investments have occurred and, in the worst case, expropriate the firm. In theory, backloading investments, production and tax payments may be used to create self-enforcing agreements which do not depend on legal enforcement. Using a new dataset covering the universe of oil majors’ assets that started production between 1974 and 1999, we indeed show in a recent CEPR Working Paper (Paltseva, Toews, and Troya-Martinez, 2022) that investments, production and tax payments are delayed by two years in countries with weak institutions relative to countries with strong institutions. Extending the dataset back to 1960 and exploiting the transition to a new world oil order where expropriation became easier, allows us to interpret our estimates as causal. In particular, prior to the transition expropriations were not feasible, due to the omnipresent and credible military threat imposed by the oil majors’ countries of origin. As the new order sat in, a new equilibrium emerged, in which expropriations became a feasible option. This transition incited an increase in expropriations and forced firms to adjust to the new reality by backloading contracts.

The Hold-up Problem

In December of 2006, when the oil price was climbing towards new heights, the Guardian reported that the Russian government was about to successfully force Shell into transferring their controlling stake in a huge liquified gas project back into the hands of the government. While officially this was motivated by environmental concerns surrounding the Sakhalin-II project, most observers agreed that this might be considered a textbook example of the hold-up problem faced by oil firms when investing in countries with limited constraints on the executive. At its core, the hold-up problem refers to the idea that the government may renege on the initial promise and appropriate a bigger share of the pie once investments have been made. Obviously, this is not an oil-specific issue and concerns any type of investment in countries with weak property rights. Academics, who worked on resolving these issues, suggest the use of self-enforcing agreements (Thomas and Worrall, 1994). These agreements use future gains from trade (as opposed to third-party enforcement) to incentivize the governments not to expropriate. And while the theoretical literature has prolifically developed over the last 30 years (Ray, 2002), to the best of our knowledge no empirical evidence has been provided on the use and dynamic patterns of self-enforcing backloaded contracts.

Data and Sample

In Paltseva, Toews and Troya-Martinez (2022), we rely on micro-level data on oil and gas projects provided by Rystad Energy, an energy consultancy based in Norway. Its database contains current and historical data on physical, geological and financial features for the universe of oil and gas assets. We focus on the assets owned by the oil majors (BP, Chevron, ConocoPhilips, Eni, ExxonMobile, Shell, and Total) using all assets that started production between 1960 and 1999, leaving us with a total of 3494 assets. An asset represents a production site with at least one well, operated by at least one firm, and with the initial property right being owned by at least one country. Being able to conduct the analysis on the asset level is particularly valuable since it allows us to control for a large number of confounding factors and rule out several alternative explanations of our main finding.

Moreover, there are three advantages of focusing our analysis on the oil and gas sector in general and the oil majors in particular. First, the sunk investments in the development of oil and gas wells are enormous, making the hold-up problem in the oil sector particularly severe. Second, oil majors have been around for many years since all of them were created before WWII. This provides us with a sufficiently long horizon to capture backloading over time. Third, the majors are simultaneously investing in many countries which provides us the necessary cross-sectional variation in institutional quality. To differentiate between countries with weak and strong institutions, we use a specific dimension from the Polity IV dataset measuring the constraints on the executive. The location of all the assets disaggregated by firm as well as a binary distinction in a country’s institutional quality is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Spatial distribution of assets and institutional quality

Note: Location and ownership of assets are provided by Rystad Energy. The executive constraint indicator is taken from Polity IV and we use the median from the period 1950 to 1975 to define whether the country is considered to have strong or weak institutions. The cut-off of 5 implies that roughly 1/3 of the countries are defined as having strong institutions and roughly 50% of all the assets which started operation between 1950 and 2000 are located in countries with weak institutions.

A Stylized Fact

For the empirical analysis, our variables of interest are investment, production and tax payments normalized by the respective asset-specific cumulative sum over a period of 35 years. The resulting cumulative shares are depicted in Figure 2. We focus on physical production which, in addition to being considered the most reliable measure of an asset’s activity, does not require discounting. Real values of investment and tax payment depict a very similar picture. Most importantly, the dashed lines illustrate that 2/3 of cumulative production shares are reached approximately two years earlier in countries with strong institutions, in comparison to countries with weak institutions. The average asset size does not differ significantly between these groups. Such delays are costly for countries with weak institutions. Our back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests that the average country loses around 120 million US$ per year due to the delayed production and the respective tax payments. We confirm that the two-year delay cannot be explained by geographical, geological or financial confounders such as the location of the well, fuel type or contract features.

Figure 2. Years to reach 66% of cumulative flows in 35 years

Note: We use the Epanechnikov kernel with an optimally chosen bandwidth to plot the cumulative production over the 35-year life span of the asset. We group countries into two groups with weak and strong institutions according to Polity IV. This figure contains assets that started producing between 1975 and 1999.

The Transition to a New World Order

To push towards a causal interpretation of the results, we exploit the global transition to a new world oil order. This change affected the probability of expropriations in countries with weak institutions while leaving countries with strong institutions unaffected. In particular, the post-WWII weakening of the OECD members as political and military actors provides a natural experiment of global proportions. Expropriations are first viewed as impossible due to the military threat of British, French and US armies, and then become possible due to a global movement aiming at returning sovereignty over natural resources to the resource-rich economies. In the words of Daniel Yergin (1993): “The postwar petroleum order in the Middle East had been developed and sustained under American-British ascendancy. By the latter half of the 1960s, the power of both nations was in political recession, and that meant the political basis for the petroleum order was also weakening. […] For some in the developing world […] the lessons of Vietnam were […] that the dangers and costs of challenging the United States were less than they had been in the past, certainly nowhere near as high as they had been for Mossadegh, [the Iranian politician challenging UK and US before the coup d’etat in 1953], while the gains could be considerable.” Consequently, the number of expropriations has grown substantially since 1968, marking the transition to a new world order (Figure 3). However, Kobrin (1980) finds that even during the peak of expropriations in 1960-1976, only less than 5 % of all foreign-owned firms in the developing countries were expropriated. We suggest that this is, at least partly, thanks to the use of backloaded self-enforcing contracts.

Figure 3. Transition to a new world order

Note: Data on firm expropriations across all industries from Kobrin (1984).

Indeed, focusing on the years around the transition to the new world oil order, we show that there have not been any differences in investment, production or tax payments dynamics between countries with weak and strong institutions in the early years of the 1960s. But investment, production and the payments of taxes started experiencing significant delays after 1968 in the countries with weak institutions, using countries with strong institutions as a control. Intuitively, the omnipresence of a credible military threat in response to an expropriation served as an effective substitute for strong local formal institutions and eliminated the need for contracts to be self-enforced and backloaded in countries with weak institutions. Once this threat disappeared, contracts had to be self-enforcing and investment, production and tax payments had to be backloaded to decrease the risk of being expropriated by the governments of resource-rich economies. Theoretically, these initial differences in contract backloading between countries with strong and weak institutions should disappear in the long run, because the future gains from trade need to materialize eventually. We confirm empirically that this point is reached on average 20 years after firms start a contractual relationship with a country.

Conclusion

We provide evidence that oil firms seem to backload contracts in countries with weak institutions. We show that such backloading appears in the data during the transition to a new world order since 1968, when firms were in need of a new mechanism to deal with weak property rights and the risk of expropriations. We estimate the cost of such delays to be around 120 US$ per country and year. While this cost is high, it is important to emphasize that in the absence of such backloading, forward-looking CEOs of oil majors would often choose not to invest in the first place, since they would anticipate the severe commitment problems (Cust and Harding, 2020). Thus, as a second-best, the cost of the backloading may be marginal compared to the value added from trade when oil majors are willing to invest in countries with weak institutions and questionable property rights.

References

- Cust, J. & Harding, T. (2020). “Institutions and the location of oil exploration”. Journal of the European Economic Association, 18(3): 1321–1350.

- Kobrin, S. J. (1980). “Foreign enterprise and forced divestment in LDCs”. International Organization, 65–88.

- Kobrin, S. J. (1984). “Expropriation as an attempt to control foreign firms in LDCs: trends from 1960 to 1979.” International Studies Quarterly, 28(3): 329–348.

- Paltseva, E, Toews, G & Troya Martinez, M. (2022). ‘I’ll pay you later: Relational Contracts in the Oil Industry‘. London, Centre for Economic Policy Research.

- Debraj, R. (2002). “The time structure of self-enforcing agreements.” Econometrica, 70(2): 547–582.

- Jonathan, T. & Worrall, T. (1994). “Foreign direct investment and the risk of expropriation.” The Review of Economic Studies, 61(1): 81–108

- Yergin, D. (2011). The prize: The epic quest for oil, money & power. Simon and Schuster.

The Expectation Boom: Evidence from the Kazakh Oil Sector

This policy brief shows that an oil price boom may trigger dissatisfaction with one’s income and that this dissatisfaction is independent of the effect of the boom on real economic conditions. Unique data from Kazakhstan allows us to quantify the impact of the recent oil price boom on satisfaction with income. Compared to other households in the country, households related to the oil sector suffer a marked drop in their satisfaction with their income during the period of high oil prices. Based on our results, we argue that an oil price boom creates a gap between people’s expectations of the benefits from the boom and the observed economic conditions. Our results call for researchers, policy makers and companies to devote more attention to the dynamics of satisfaction, not only during resource busts but also during resource booms.

Local Impact of Natural Resources

Often, resource wealth is associated with a curse, slowing economic growth in resource-rich developing countries (Venables, 2016). While traditionally, this relationship has been explored across countries, more recently, the literature started exploiting plausibly exogenous spatial variation in resource wealth within countries (Cust and Polhekke, 2015). We now know that resources can generate local economic wealth (Aragon and Rud, 2013), while also attracting corrupted individuals to power (Asher and Novosad, 2018) and triggering local conflicts (Berman et al. 2017; Rigterink, 2018). But, up to now, we know very little about the impact of resource booms on individuals’ perceptions. Since perceptions and behavioral biases may also drive actions, understanding whether and how resources affect perceptions is key in understanding the local impact of natural resources (Collier, 2017).

In a new working paper (Girard, Kudebayeva and Toews, 2020) we use Kazakhstan as a case study to shed more light on the importance of such perceptions. We document the conditions that preceded and presumably contributed to the violent conflicts in the oil rich districts of Kazakhstan in 2011. We show that periods of high oil prices can actually lead to a drop in reported satisfaction with income. This implies that due to mere changes in perceptions, which are not reflected in economic conditions, a large number of people may experience a significant drop in satisfaction with income, creating a fertile ground for conflicts.

The Zhanaozen Conflict

Our attention to the case of Kazakhstan is driven by the extreme events that took place in 2011 in the city of Zhanaozen, a booming oil town in the west of the country’s desert. In May 2011, after several years of high oil prices, private sector workers in Zhanaozen demanded amendments to the pre-existing collective bargaining agreement asking in particular for a raise in wages. Difficulties in negotiating an agreement resulted in local oil companies dismissing more than 2000 employees in the summer of 2011 and oil production dropping by 7% in the first three quarters of 2011 relative to the same period in the previous year. At the conflict climax, the police tried to clear the central square of Zhanaozen for the upcoming preparations of the Independence Day, resulting in the killing of 17 and the injuring of over 100 people (Satpayev and Umbetaliyeva, 2015).

Oil Price Boom in Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan offers an ideal case study for our research question for two reasons. First, the government of Kazakhstan closely monitored citizens’ satisfaction with income throughout most of the 2000s using a representative household panel survey. Using this data allows us to link variation in the price of oil to within household variations in satisfaction with income – conditional on household income, thus, capturing the changing perceptions of household heads regarding their income. Secondly, Kazakhstan is a small open resource rich economy, with sparsely populated and remote districts, whose economic activity nearly exclusively depends on the extraction of oil and gas. The fact that Kazakhstan is a small open economy implies that changes in the oil price may be treated as exogenous to households located in Kazakhstan. The spatial isolation of the oil rich districts allows us to consider the group of household heads employed in the private sector in the oil rich districts as either directly or indirectly involved in the extraction of oil and gas.

Figure 1. Kazakhstan

Source: Resource rich districts are indicated as treated. The information on the spatial identification of oil and gas rich district is taken from the Petroleum Encyclopedia of Kazakhstan and captures more than 90% of total oil and gas production in Kazakhstan (Munayshy Public Foundation, 2005).

Satisfaction With Income

To identify the effect of oil price fluctuations on satisfaction with income, we exploit three sources of variation: location of the household, sectoral employment and time. The group affected by the price of oil is the group of oil-related households. Oil-related households consist of households whose head is employed in the private sector of the oil rich districts of Kazakhstan, and who are thus the closest to the oil sector (by nature of their activity and place of residence). The differential evolutions in satisfaction of household heads employed in other sectors and households located in other districts – in other words, households which are more remote from oil and gas extraction than the oil-related households provide a plausible counterfactual.

The main results are depicted in Figure 2 which represents the relationship between income and satisfaction for 8 groups based on the three sources of variation: oil price (which was low between the years 2001 and 2004, and high between 2005 and 2009), place of residence as indicated in Figure 1, and sector of activity.

First, we note that the relationship between income and satisfaction is upward sloping: reported satisfaction with household income increases with income. This is intuitive. Focusing on oil poor districts that appear in the bottom panel, we observe that the relation between satisfaction and income is virtually the same across sectors and time periods of low and high prices of oil. This is, however, not true for oil-rich districts, which are depicted in the top panel. Here, the relationship between income and satisfaction only remains unaffected across time for household heads who are not employed in the private sector. The picture changes if we turn to household heads employed in the private sector, who are the oil-related household heads. The satisfaction with the income of oil-related household heads shifts downwards, compared to other households, in the period of high oil prices (years 2005-2009). This downward shift is even more striking since oil-related household heads valued their income relatively higher than other households during the period of low oil prices (2001-2004).

Figure 2. Satisfaction with Income

Source: Authors’ calculations based on satisfaction with income and household income as reported in the Household Survey of Kazakhstan. The figures above depict the relationship between logged household income per family member and reported satisfaction with income by the head of the household on a scale from 1 to 5. The relationship is depicted conditional on household fixed effects and year fixed effects. The former account for time-invariant household specific characteristics such as individual biases. The latter account for Kazakhstan specific shocks affecting households in oil poor and oil rich districts simultaneously due to political and economic business cycles. As a result, the relationship between logged income per family member and satisfaction is normalized to zero in both dimensions.

Lastly, we document that the negative variation in satisfaction is related to the contemporaneous change in the price of oil. The satisfaction with income is not persistent, it is unrelated to past and future levels of the oil price.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that oil prices fluctuations can be linked to the individual’s perception of income. The fact that oil-related household heads express a strong dissatisfaction compared to other household heads may help to understand what made December 2011 possible, when 17 people were killed and over 100 people were wounded in Zhanaozen. If generalizable, such dynamics of perceived satisfaction with income should be kept in mind by both policy makers and extractive companies not only during resource busts but also during resource booms.

References

- Aragon, Fernando M. and Juan Pablo Rud (2013). “Natural resources and local communities: evidence from a Peruvian gold mine.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 5(2):1–25.

- Asher, Sam and Paul Novosad (2018). Rent-seeking and criminal politicians: Evidence from mining booms. Working Paper.

- Berman, Nicolas, Mathieu Couttenier, Dominic Rohner and Mathias Thoenig (2017). “This Mine Is Mine! How Minerals Fuel Conflicts in Africa.” American Economic Review 107(6):1564–1610.

- Collier, Paul (2017). “The institutional and psychological foundations of natural resource policies.” The Journal of Development Studies 53(2):217–228.

- Cust, James and Steven Poelhekke (2015). “The local economic impacts of natural resource extraction.” Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ., 7(1):251–268.

- Girard, Victoire, Alma Kudebayeva and Gerhard Toews (2020). “Inflated Expectations and Commodity Prices: Evidence from Kazakhstan.“ GLO Discussion Paper Series 469.

- Rigterink, Anouk S. (2020). “Diamonds, rebel’s and farmer’s best friend: Impact of variation in the price of a lootable, labour-intensive natural resource on the intensity of violent conflict.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 64(1):90–126.

- Munayshy Public Foundation (2005). “Petroleum Encyclopedia of Kazakhstan.”

- Girard, Victoire, Alma Kudebayeva and Gerhard Toews (2020). “Inflated Expectations and Commodity Prices: Evidence from Kazakhstan” Working Paper.

- Satpayev, Dossym and Umbetaliyeva, Òolganay (2015). “The protests in Zhanaozen and the Kazakh oil sector: Conflicting interests in a rentier state.” Journal of Eurasian Studies 6(2):122–129.

- Venables, Anthony J. (2016): “Using Natural Resources for Development: Why Has It Proven So Difficult?” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 30, 161 – 84.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in policy briefs and other publications are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect those of the FREE Network and its research institutes.

Resource Discoveries, FDI Bonanzas and Local Multipliers: Evidence from Mozambique

Giant oil and gas discoveries in developing countries trigger FDI bonanzas. Across countries, it is shown that in the 2 years following a discovery, the creation of FDI jobs increases by 54% through the establishment of new projects in non-resource sectors such as manufacturing, retail, business services and construction. Using Mozambique’s gas driven FDI bonanza as a case study we show that the local job multiplier of FDI projects in Mozambique is large and results in 4.4 to 6.5 additional jobs, half of which are informal.

Natural Resources, FDI Job Multiplier and Economic Development

Large resource wealth has for several decades been associated with a curse, slowing economic growth in resource-rich developing countries (Venables, 2016). More recently, this wisdom has been questioned by several studies. Arezki et al. (2017) point out that giant discoveries trigger short-run economic booms before windfalls from resources start pouring in. And Smith (2017) provides evidence for a positive relationship between resource discoveries and GDP per capita across countries, which persists in the long term.

In a new paper (Toews and Vézina, 2018) we contribute to this research by showing that giant oil and gas discoveries in developing countries trigger foreign direct investment (FDI) bonanzas in non-extraction sectors. FDI has long been considered a key part of economic development since it is associated with transfers of technology, skills, higher wages, and with backward and forward linkages with local firms (Hirschman, 1957; Javorcik, 2015). Using Mozambique, where a giant offshore gas discovery has been made in 2009, as a case study, we estimate the local multiplier of FDI projects. We find that the FDI job multiplier in Mozambique is large, highlighting the job creation potential of FDI in developing countries.

Resource Discoveries and FDI Bonanzas

In our study we focus on jobs created by FDI bonanzas triggered by resource discoveries. Multinationals might invest in countries being blessed by giant discoveries for a variety of reasons before production starts. First, they might expect to benefit from the decisions of oil and gas companies to increase investment in local infrastructure and to increase demand for local services provided by law firms and environmental consultancies. Second, multinationals may also expect governments and consumers to bring forward expenditure and investment by borrowing. Finally, multinationals might invest since particularly large discoveries have the potential to operate as a signal leading to a coordinated investment by a large number of multinationals from a variety of industries and countries.

Using data from fDi Markets we show that, indeed, FDI flows into non-extraction sectors following a discovery. FDI increases across sectors and by doing so creates jobs in industries such as manufacturing, retail, business services and construction. Using Mozambique as a case study we show that following the gas discovery, multinationals decided to invest in Mozambique triggering job creation in non-extraction FDI to skyrocket (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. FDI Bonanza in Mozambique

Source: Author’s calculations using fDiMarkets data.

FDI Job Multiplier

Using the FDI bonanza in Mozambique as a natural experiment, we proceed by estimating the FDI job multiplier for Mozambique. The concept of the local job multiplier boils down to the idea that every time a job is created by attracting a new business, additional jobs are created in the same locality. In our case, FDI jobs are expected to have a multiplier effect due to two distinct channels. Newly created and well paid FDI jobs are likely to increase local income and in turn the demand for local goods and services (Moretti, 2010). Additionally, backward and forward linkages between multinationals and local firms increase the demand for local goods and services (Javorcik, 2004).

Using concurrent waves of household surveys and firm censuses we estimate the local FDI multiplier for Mozambique to be large. In particular, we find that every additional FDI job results in 4.4 to 6.5 additional local jobs. Due to the combined use of household survey and the firm census we are also able to conclude that only half of these jobs are created in the formal sector, while the other half of the jobs are created informally.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that giant oil and gas discoveries in developing countries lead to simultaneous foreign direct investment in various sectors including manufacturing. Our results also highlight the job creation potential of FDI projects in developing countries. Jointly, our results imply that giant discoveries do have the potential to trigger extraordinary employment booms and, thus, provide a window of opportunity for a growth takeoff in developing countries.

References

- Arezki, R., V. A. Ramey, and L. Sheng (2017): “News Shocks in Open Economies: Evidence from Giant Oil Discoveries,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 132, 103.

- Hirschman, A. O. (1957): “Investment Policies and “Dualism” in Underdeveloped Countries,” The American Economic Review, 47, 550 – 570.

- Javorcik, B. S. (2004): “Does Foreign Direct Investment Increase the Productivity of Domestic Firms? In Search of Spillovers Through Backward Linkages,” American Economic Review, 94, 605 – 627.

- Javorcik, B. S. (2015): “Does FDI Bring Good Jobs to Host Countries?” World Bank Research Observer, 30, 74 – 94.

- Moretti, E. (2010): “Local Multipliers,” American Economic Review, 100, 373 – 377.

- Smith, Brock. “The resource curse exorcised: Evidence from a panel of countries.” Journal of Development Economics: 116 (2015): 57-73.

- Toews and Vézina, (2018): “Resource discoveries, FDI bonanzas and local multipliers: An illustration from Mozambique” Working Paper.

- Venables, A. J. (2016): “Using Natural Resources for Development: Why Has It Proven So Difficult?” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 30, 161 – 84.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in policy briefs and other publications are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect those of the FREE Network and its research institutes.

Empirical Evidence on Natural Resources and Corruption

This policy brief addresses the relationship between resource wealth and a particular institutional outcome – corruption. We overview some recent empirical evidence on this relationship and outline results of an on-going research project addressing a particular aspect of resource-related political corruption: transformation of resource rents into personal wealth hidden at off-shore deposits. The preliminary results from this project suggest that at least 8 percent of oil and gas rents are converted into personal political rents in countries with poor political institutions.

Are Natural Resources Good or Bad for Development?

Natural resources development undoubtedly plays an important role in the economies of many countries. Whether their contribution to development is positive or negative is, however, a contested and difficult question. Arguably, countries like Australia, Botswana, and Norway have gained enormously over long periods from sustained natural resources development. Others, such as Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Russia, have achieved significant economic growth through natural resources development but perhaps at the expense of institutional progress. In contrast, in some countries—such as Angola and Sierra Leone—natural resources development has been at the heart of violent conflicts, with devastating consequences for society. With many developing countries being highly resource-dependent, a deeper understanding of the sources of success and the risks associated with natural resources development is highly relevant. This brief reviews the main issues and points to key policy challenges for transforming resource rents from natural resources development into a driver rather than a detriment to overall development.

Is it good for a country to be rich in natural resources? Superficially, the answer to this question would obviously seem to be “yes”. How could it ever be negative to have something in addition to labor and produced capital? How could it be negative to have something valuable “for free”? Yet, the answer is far from that simple and one can relatively quickly come up with counterarguments: “Having natural resources takes away incentives to develop other areas of the economy which are potentially more important for long-run growth”; “Natural resource-income can cause corruption or be a source of conflict”, etc.

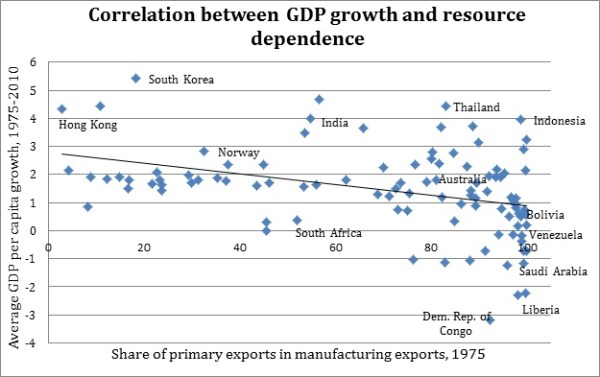

Looking at some of the starkest cases, the “benefits” of resources can indeed be questioned. Take the Democratic Republic of Congo for example. It is the world’s largest producer of cobalt (49% of the world’s production in 2009) and of industrial diamonds (30%). It is also a large producer of gemstone diamonds (6%), it has around 2/3 of the world’s deposits of coltan and significant deposits of copper and tin. At the same time, it has the world’s worst growth rate and the 8th lowest GDP per capita over the last 40 years.[1] The picture for Sierra Leone and Liberia is very similar – they possess immense natural wealth, yet they are found among the worst performers both in terms of economic growth and GDP per capita. While the experiences of countries such as Bolivia and Venezuela are not as extreme their resource wealth in terms of natural gas and oil, respectively, seems to have brought serious problems in terms of low growth, increased inequality and corruption. When one, on top of this, adds that some of the world’s fastest-growing economies over the past decades – such as Hong Kong, South Korea and Singapore – have no natural wealth the picture that emerges is that resources seem to be negative for development.

These are not isolated examples. By now, it is a well-established fact that there is a robust negative relationship between a country’s share of primary exports in GDP and its subsequent economic growth. This relationship, first established in the seminal paper by Sachs & Warner (1995) is the basis for what is often referred to as the resource curse, that is, the idea that resource dependence undermines long-run economic performance.[2]

Based on the World Development Indicators database (World Bank). Primary exports consist of agricultural raw materials exports, fuel exports, ores and metals, and food exports.

At the same time, there are numerous countries that provide counterexamples to this idea. Being the second largest exporter of natural gas and the fifth largest of oil, Norway is one of the richest world economies. Botswana produces 29% of the world’s gemstone diamonds and has been one of the fastest-growing countries over the last 40 years. Australia, Chile, and Malaysia are other examples of countries that have performed well, not just despite their resource wealth, but, to a large extent, due to it.

Given these examples the relevant question becomes not “Are resources good or bad for development?” but rather “Under what circumstances are resources good and when are they bad for development?. As Rick van der Ploeg (2011) puts it in a recent overview: “the interesting question is why some resource-rich economies [.] are successful while others [.] perform badly despite their immense natural wealth”. To begin to answer this question it is useful to first review some of the many theoretical explanations that have been suggested and to see what empirical support they have received. Clearly, our overview is far from complete but we think it gives a fair picture of how we have arrived at our current stage of knowledge.[3]

Theories and Evidence

The most well-known economic explanation of the resources curse suggests that a resource windfall generates additional wealth, which raises the prices of non-tradable goods, such as services. This, in turn, leads to real exchange rate appreciation and higher wages in the service sector. The resulting reallocation of capital and labor to the non-tradable sector and to the resource sector causes the manufacturing sector to contract (so-called “de-industrialization”). This mechanism is usually referred to as “Dutch disease” due to the real exchange rate appreciation and decrease in manufacturing exports observed in the Netherlands following the discovery of North Sea gas in the late 1950s. Of course, the contraction of the manufacturing sector is not necessarily harmful per se, but if manufacturing has a higher impact on human capital development, product quality improvements and on the development of new products, this development lowers long-run growth.[4] Other theories have focused on the problems related to the increased volatility that comes with high resource dependence. In particular, it has been suggested that irreversible and long-term investments such as education decrease as volatility goes up. If human capital accumulation is important for long-run growth this is yet another potential problem of resource wealth.

The empirical support for the Dutch disease and related mechanisms is mixed. Some authors find that a resource boom causes a decline in manufacturing exports and an expansion of the service sector (e.g. Harding and Venables (2010)), others do not (e.g. Sala-i-Martin and Subramanian (2003)). But even the studies that do find evidence of the Dutch disease mechanism, usually do not analyze its effect on the growth rates. In principle, Dutch disease could be at work without this hurting growth. Another problem is that the Dutch disease theory suggests that natural resources are equally bad for development across countries. This means that the theories cannot account for the great heterogeneity of observed outcomes, that is, they cannot explain why some countries fail and others succeed at a given level of resource dependence. The same goes for the possibility that natural resources create disincentives for education. Gylfason 2001, Stijns (2006) and Suslova and Volchkova (2007) find evidence of lower human capital investment in resource-rich countries but the theory cannot explain differences across (equally) resource-rich countries.

As a result, greater attention has been devoted to the political-economic explanations of the resource curse. The main idea in recent work is that the impact of resources on development is heavily dependent on the institutional environment. If the institutions provide good protection of property rights and are favourable to productive and entrepreneurial activities, natural resources are likely to benefit the economy by being a source of income, new investment opportunities, and of potential positive spillovers to the rest of the economy. However, if property rights are insecure and institutions are “grabber-friendly”, the resource windfall instead gives rise to rent-seeking, corruption and conflict, which have a negative effect on the country’s development and growth. In short, resources have different effects depending on the institutional environment. If institutions are good enough resources have a positive effect on economic outcomes, if institutions are bad, so are resources for development.

Mehlum, Moene and Torvik (2006) develop a theoretical model for this effect and also find empirical support for the idea. In resource-rich countries with bad institutions incentives become geared towards “grabbing resource rents” while in countries where institutions render such activities difficult resources contribute positively to growth. Boschini, Pettersson and Roine (2007) provide a similar explanation but also stress the importance of the type of resources that dominate. They show that if a country’s institutions are bad, “appropriable” resources (i.e., resources that are more valuable, more concentrated geographically, easier to transport etc. – such as gold or diamonds) are more “dangerous” for economic growth. The effect is reversed for good institutions – gold and diamonds do more good than less appropriable resources. In turn, better institutions are more important in avoiding the resource curse with precious metals and diamonds than with mineral production. The following graph illustrates their result by showing the marginal effects of different resources on growth for varying institutional quality. Distinguishing the growth contribution of mineral production in countries with good institutions with the effect in countries with bad institutions, the left panel shows a positive effect in the former and a negative one in the latter case. The right-hand panel illustrates the corresponding, steeper effects when isolating only precious metals and diamond production.

Even if these papers provide important insights and allow for the possibility of similar resource endowments having variable effects depending on the institutional setting, two major problems still remain. First, the measures of “institutional quality” are broad averages of institutional outcomes (rather than rules).[5] Even if Boschini et al. (2007), and in particular Boschini, Pettersson and Roine (2011) test the robustness of the interaction result using alternative institutional measures (including the Polity IV measure of the degree of democracy) it remains an important issue to understand more precisely which aspects of institutions that matter. An attempt at studying a particular aspect of this question is the paper by Andersen and Aslaksen (2008), which shows that presidential democracies are subject to the resource curse, while it is not present in parliamentary democracies. They argue that this result is due to higher accountability and better representation of the parliamentary regimes.

A second remaining issue is that even if one concludes that the impact of natural resources differs across institutional environments it is an obvious possibility that natural resources have an impact on the chosen policies and institutional arrangements. For example, access to resource rents may provide additional incentives for the current ruler to stay in power and to block institutional reforms that threaten his power, such as democratization. In a well-known paper with the catchy title “Does oil hinder democracy?” Ross (2001) uses pooled cross-country data to establish a negative correlation between resource dependence and democracy.

However, one needs to be careful in distinguishing such a correlation from a causal effect. There are at least two issues that can affect the interpretation: First, there could be an omitted variable bias, that is, the natural resource dependence and institutional environment can be influenced by an unobserved country-specific variable, such as historically given institutions (which in turn could be the result of unobserved effects of resources in previous periods), culture, etc. For the same reason, cross-country comparisons may also be misleading. One way of dealing with this problem is to use fixed-effect panel regressions to eliminate the effect of the country-specific unobserved characteristics. This approach produces mixed empirical results: in the analysis of Haber and Menaldo (2011) the effect of resources on democracy disappears, while Aslaksen (2010) and Andersen and Ross (2011) find support for a political resource curse.

Second, the measures of natural resource wealth may be endogenous to institutions and, in particular, its level of democracy. For example, the level of oil production and even the efforts put into oil discovery can be affected by the decisions of (and constraints on) those in power. Thereby one would need to find instrumental variables that influence the level of democracy only through the resource measures.[6] Tsui (2011) investigates the causal relationship between democracy and resources by looking at the impact of oil discovery event(s) on a cross-country sample. His identification strategy is based on using the exogenous variation in oil endowments (an estimate of the total amount of oil initially in place) to instrument for the amount of total discovered oil to date. The idea is that, while the amount of oil discovered could well be influenced by the institutional environment, the size of the oil endowment is determined only by nature. Tsui’s findings also support the political resource curse story.

There are also numerous studies about the effect of resources on particular institutional aspects and policies. For example, Beck and Laeven (2006) find that resource wealth delayed reform in Eastern Europe and the CIS, Desai, Olofsgård and Yousef (2009) point to natural resource income as central for the possibilities of autocratic governments to remain in power through buying support, Egorov et. al. (2009) show that there is fewer media freedom in oil-rich economies, with the effect being the strongest for the autocratic regimes. Andersen and Aslaksen (2011) find that natural resource wealth only affects leadership duration in non-democratic regimes. Moreover, in these countries, less appropriable resources extend the term in power (in line with the ruler incentive argument above), while more appropriable resources, such as diamonds, shorten political survival (perhaps, due to increased competition for power). Several papers show that in a bad institutional environment natural resources increase corruption (e.g., Bhattacharyya and Hodler (2010) or Vincente (2010)), and reduce corporate transparency (Durnev and Guriev (2011)).

Implications for Policy

Overall the literature points to potential economic as well as political problems connected to natural resources. Even if some issues remain contested it seems clear that many of the economic problems are solvable with appropriate policy measures and in general that natural resources can have positive effects on economic development given the right institutional setting. However, it seems equally clear that natural resource wealth, especially in initially weak institutional settings, tends to delay diversification and reforms, and also increases incentives to engage in various types of rent-seeking. In autocratic settings, resource incomes can also be used by the elite to strengthen their hold on power.

Successful examples of managing resource wealth, such as the establishment of sovereign wealth funds that can both reduce the volatility and create transparency and also smooth the use of resource incomes over time, are not always optimal or easily implementable. Using the money for large investments could be perfectly legitimate and consumption should be skewed toward the present in a capital-scarce developing setting (as shown by van der Ploeg and Venables, 2011). But no matter what we think we know about the optimal policy it still has to be implemented and if the institutional setting is weak the problems are very real. This is just because of potentially corrupt governments but also due to the difficulty to make credible commitments even for perfectly benevolent politicians (see e.g. Desai, Olofgård and Yousef, 2009).

Many political leaders in resource-rich countries have pointed to the hopelessness of their situation and have expressed a wish to rather be without their natural wealth. Such conclusions are unnecessarily pessimistic. Even if it is true that the policy implications from the literature more or less boil down to a catch-22 combination of 1) “Resources are bad (only) if you have poor institutions, so make sure you develop good institutions if you have resource wealth” and 2) “Natural resources have a tendency to impede good institutional development”, there are possibilities. Some countries have succeeded in using their resource wealth to develop and arguably strengthen their institutions. Even if it is often noted that Botswana had relatively good institutions already at the time of independence, it was still a poor country with no democratic history facing the challenge of developing a country more or less from scratch. And at the time of independence, they also discovered and started mining diamonds which have since been an important source both of growth and government revenue. This development has to a large part been due to good, prudent policy.

There is nothing inevitable about the adverse effects of natural resources but resource-rich developing countries must face the challenges that come with having such wealth and use it wisely. The first step is surely to understand the potential problems and to be explicit and transparent about how one intends to deal with them.

References

- Andersen, J. J. and Aslaksen, S., 2008. “Constitutions and the resource curse.” Journal of Development Economics, Volume 87, Issue 2.

- Andersen, J. J. and Aslaksen, S., 2011. “Oil and political survival.” mimeo.

- Andersen, J. J. and Ross, M., 2011, “Making the Resource Curse Disappear: A re-examination of Haber and Menaldo’s: “Do Natural Resources Fuel Authoritarianism?”.” mimeo.

- Aslaksen, S., 2010. “Oil and Democracy – More than a Cross-Country Correlation?,” Journal of Peace Research, vol. 47(4).

- Beck, T., and Laeven, L., 2006. “Institution Building and Growth in Transition Economies.” CEPR Discussion Paper 5718, Centre for Economic Policy Research:London.

- Bhattacharyya, S., and Hodler, R., 2010. “Natural resources, democracy and corruption” European Economic Review, Elsevier, vol. 54(4).

- Boschini, A.D., Pettersson, J. and Roine, J., 2007. “Resource curse or not: a question of appropriability” Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 109.

- Boschini, A.D., Pettersson, J. and Roine, J., 2011. “Unbundling the resource curse” mimeo.

- David, P. A., and Wright, G.. 1997. “The Genesis of American Resource Abundance” Industrial and Corporate Change 6.

- Desai, R. M., Olofsgård, A. and Yousef, T., 2009. “The Logic of Authoritarian Bargains” Economics & Politics, Vol. 21, Issue 1.

- Durnev, A. and Guriev, S. M., 2011. ”Expropriation Risk and Firm Growth: A Corporate Transparency Channel.”, mimeo

- Egorov, G., Guriev, S. M. and Sonin, K., 2009. “Why Resource-Poor Dictators Allow Freer Media: A Theory and Evidence from Panel Data.” American Political Science Review, Vol. 103, No. 4.

- Gylfason, T., 2001. “Nature, Power, and Growth” Scottish Journal of Political Economy, Scottish Economic Society, vol. 48(5).

- Gylfason, T., Herbertsson, T. T., and Zoega, G., 1999. “A mixed blessing” Macroeconomic Dynamics, 3.

- Findlay, R. and Lundahl M., 1999. “Resource-Led Growth: A Long-Term Perspective.” Helsinki: World Institute for Development Economics Research.

- Frankel, J. A., 2010 “The Natural Resource Curse: A Survey.” HKS Working Paper No. RWP10-005.

- Haber, S. H. and Menaldo, V. A., 2011. “Do Natural Resources Fuel Authoritarianism? A Reappraisal of the Resource Curse.” American Political Science Review, Vol. 105, No. 1.

- Harding, T. and Venables, A.J., 2011. “Exports, imports and foreign exchange windfalls.” mimeo.

- Hausmann R., Hwang J. and Rodrik, D., 2007. “What you export matters.” Journal of Economic Growth, Springer, vol. 12(1).

- Leite, C. A. and Weidmann, J., 1999. “Does Mother Nature Corrupt? Natural Resources, Corruption, and Economic Growth.” IMF Working Paper No. 99/85.

- Mehlum, H., Moene, K. and Torvik, R., 2006. ”Institutions and the resource curse.” Economic Journal, 116.

- Montague, D., 2002. “Stolen Goods: Coltan and Conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo.” SAISReview – Volume 22, Number 1, Winter-Spring, pp. 103-118

- van der Ploeg, F., 2011. “Natural Resources: Curse or Blessing?.” Journal of Economic Literature, American Economic Association, vol. 49(2).

- van der Ploeg, F. and Venables, A. J., 2011. “Harnessing Windfall Revenues: Optimal Policies for Resource-Rich Developing Economies.” Economic Journal, Royal Economic Society, vol. 121(551).

- Ross, M.L., 2001. “Does Oil Hinder Democracy?” World Politics, 53(3).

- Sachs, J. D. and Warner, A. M., 1995. “Natural Resource Abundance and Economic Growth.” NBER Working Papers 5398, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

- Sala-I-Martin, X., Doppelhofer, G. and Miller, R. I., 2004. “Determinants of Long-Term Growth: A Bayesian Averaging of Classical Estimates (BACE) Approach.” American Economic Review, American Economic Association, vol. 94(4).

- Sala-I-Martin, X., and Subramanian, A., 2003. “Addressing the Natural Resource Curse: An Illustration from Nigeria.” NBER Working Paper 9804.

- Stijns, J.-P., 2006. “Natural resource abundance and human capital accumulation.” World Development, Elsevier, vol. 34(6).

- Suslova, E. and Volchkova, N., 2007. “Human Capital, Industrial Growth and Resource Curse.” Working Papers WP13_2007_11, Laboratory for Macroeconomic Analysis, HSE.

- Torvik, R., 2009. “Why do some resource-abundant countries succeed while others do not?”, Oxford Review of Economic Policy, vol. 25(2).

- Tsui, K. K., 2011. “More Oil, Less Democracy: Evidence from Worldwide Crude Oil Discoveries.” The Economic Journal, 121.

- Vincente, P., 2010. “Does Oil Corrupt? Evidence from a Natural Experiment in West Africa,” Journal of Development Economics, 92(1).

- Wright, G., 1990. “The Origins of American Industrial Success, 1879-1940.” American Economic Review 80.

Footnotes

[1] Based on World Development Indicators database (World Bank).

[2] Its robustness has been confirmed in, for example, Gylfason, Herbertsson and Zoega (1999), Leite and Weidmann (1999), Sachs and Warner (2001) and Sala-i-Martin and Subramanian (2003). Doppelhoefer, Miller and Sala-i-Martin (2004) find that the negative relation between the fraction of primary exports in total exports and growth is one of 11 variables which is robust when estimates are constructed as weighted averages of basically every possible combination of included variables.

[3] The interested reader should consult more extensive overviews such as Torvik (2009), Frankel (2010) or van der Ploeg (2011).

[4] This assumption has been criticized by, for example, Wright (1990), David and Wright (1997), and Findlay and Lundahl (1999) who all point to historical examples where resource extraction has been a driver for the development of new technology. On the other hand others, e.g. Hausmann, Hwang and Rodrik (2007), provide evidence that export product sophistication predicts higher growth.

[5] The distinction between using institutional outcomes rather than institutional rules has been much debated in the literature on the importance of institutions in general. It is, for example, possible for a dictator to choose to enforce good property rights protection even if this is something typically associated with democracy.

[6] The studies by Boschini, Pettersson and Roine (2007) and (2011) also use instrumental variables to try to account for the potential endogeneity problems. The results are in line with the OLS results but instruments are weak in this setting.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in policy briefs and other publications are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect those of the FREE Network and its research institutes.