Author: Admin

More Commitment is Needed to Improve Efficiency in EU Fiscal Spending

The member states of the European Union coordinate on many policy areas. The joint implementation of public good type projects, however, has stalled. Centralized fiscal spending in the European Union remains small and there exists an overwhelming perception that the available funds are inefficiently allocated. Too little commitment, frequent rounds of renegotiation and unanimous decision rules can explain this pattern.

Currently, the EU allocates only about 0.4% of its aggregate GDP to centralized public goods spending (European Commission (2014)). This is surprising given the fiscal federalism literature’s classic predictions of efficiency gains from coordinated public goods provision (see for example Oates (1972) and the more recent contributions of Lockwood (2002) and Besley and Coate (2003) for a discussion). Yet, recent proposals to expand centralized fiscal spending in the EU have been met with skepticism if not outright rejection. The most frequently cited argument claims existing funds are already being allocated inefficiently and any expansion of centralized spending would turn the EU into a mere transfer union (Dellmuth and Stoffel (2012) provide a review).

Centralized fiscal spending in the EU is provided through the “Structural and Cohesion Funds”, which are part of the EU’s so called “Regional Policy” and were initially instituted in 1957 by the Treaty of Rome for the union to “develop and pursue its actions leading to the strengthening of its economic, social and territorial cohesion” (TFEU (1957), Article 174). At that point, the six founding members agreed it was important to “strengthen the unity of their economies and to ensure their harmonious development by reducing the difference existing between the various regions and the backwardness of the less favoured regions” (stated in the preamble of the same treaty). A reform in 1988 has further emphasized this goal by explicitly naming cohesion and convergence as the main objectives of regional policy in the EU.

Today, actual fiscal spending in the EU is far from achieving this goal. The initially agreed upon contribution schemes are often reduced by nation specific discounts and special provisions as the most recent budget negotiations for the 2014-2020 spending cycle showed yet again. Moreover, the perception is that available funds are being spent inefficiently (see for example Sala-i-Martin (1996) and Boldrin and Canova (2001)).

Figure 1. 2011 EU Structural and Cohesion Funds

Figure 1 shows the national contributions to the structural funds as well as EU spending from that same budget in each member nation in per capita terms (data published by the European Commission). If fiscal spending was efficiently structured to achieve the above mentioned goal of convergence, one would observe a strong negative correlation between contributions and spending. The data shows, however, that while some redistribution is clearly implemented, rich nations still receive large amounts of the funds meant to alleviate inequality in the union (see Swidlicki et al. (2012) for a detailed analysis of this pattern for the contributions to and spending of structural funds in the UK).

What prevents a group of sovereign nations from effectively conducting the basic fiscal task of raising and allocating a budget to achieve an agreed upon common goal? In a recent paper, we theoretically examine the structure of the bargaining and allocation process employed by the EU (Simon and Valasek (2013)). Our analysis suggests that efficiency both in terms of raising contributions and allocating fiscal spending cannot be expected under the current institutional setting. While poorly performing local governments, low human capital in recipient regions, and corruption might all play a role in creating inefficiency (see for example Pisani-Ferry et al. (2011) for a discussion of the Greek case), improving upon those will only solve part of the problem.

We demonstrate that the inefficiency of EU spending in promoting the goal of convergence can be explained by the underlying institutional structure of the EU, where sovereign nations bargain over outcomes in the shadow of veto. Specifically, we model the outcome of the frequent negotiation rounds employed by the EU as the so-called Nash bargaining solution, explicitly taking into account the possibility for each member nation to veto and to withdraw its contribution (as the UK threatened in the most recent budget negotiations). It turns out that it is precisely the combination of voluntary participation, unanimity decision rule and the lack of a binding commitment to contribute to the joint budget that generally prevents efficient fiscal spending. In such a supranational setting, the distribution of relative bargaining power arises endogenously from countries’ contributions and their preferences over different joint projects. This creates a link between contributions to and allocation of the budget that is absent in federations, where contributions to the federal budget cannot simply be withdrawn and spending vetoed. Since the EU members lack such commitment, this link will necessarily lead to an inefficient outcome.

Why Does the EU Have These Institutions?

If the currently employed bargaining process cannot lead to an efficient outcome, why then did the EU member nations not institute a different allocation process right from the start? Of course, agreeing on a binding contract without the possibility for individual veto is politically difficult. More complicated bargaining processes may also be much more costly in terms of administration than is relying on informal negotiations and mutual agreement. Our analysis suggests another alternative: If the potential members of the union are homogeneous with respect to their income and the social usefulness (or spillovers) of the projects they propose to be implemented in the union, then Nash bargaining will actually lead to the budget being raised and allocated efficiently. The intuition behind this result is simple: If all countries have the same endowment, their opportunity costs of contributing to the joint budget are the same. Moreover, symmetric spillovers do not give one country a higher incentive to participate in the union than the other. Consequently, all countries have the exact same bargaining position. Thus, equilibrium in the bargaining game must produce equal surpluses for all nations. At the same time, with incomes and spillovers perfectly symmetric, the efficient allocation also produces the same surplus for each nation, so that it coincides with the Nash bargaining solution. It is important to notice, though, that symmetric income and spillovers do not imply homogeneous preferences: Each nation can still prefer its “own” project to the others. Instead, symmetry leads to a perfectly uniform distribution of bargaining power in equilibrium. Moreover, our analysis shows that efficiency is achieved if the union budget is small relative to domestic consumption and member countries have similar incomes.

This resonates well with the history of the European Union. In fact, the disparities between the founding members were not large, so that the current bargaining institutions could reasonably have been expected to yield efficiency. Only the inclusion of Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Spain created a more economically diverse community (European Movement (2010)). Our model shows that as the asymmetries between member countries or the importance of the union relative to domestic consumption grow, Nash bargaining leads to increasingly inefficient outcomes. Figure 2 shows this effect for a union of two nations. Keeping aggregate income constant and assuming symmetric spillovers between the two nations’ preferred projects, we vary asymmetry in their domestic incomes. The graphs show the Nash bargaining outcome (marked with superscript NB) compared to the generally efficient solution. As country A’s income increases, so does its outside option (i.e. all else equal, the higher the income, the less a country would lose if the joint projects were not implemented). Thus, country A’s bargaining position relative to country B increases in equilibrium, leading to an inefficient outcome. The allocation of funds to the union projects (upper right panel) depicts this channel very clearly: While the efficient allocation is independent from the distribution of national incomes, the Nash bargaining solution reflects the changing distribution of power. Nation A is able to tilt the allocation more toward its own preferred project the higher its income. Moreover, it is able to negotiate a “discount” for its contribution. While its contribution (labeled xa) does increase with its income (labeled ya), country A still pays less than would be budgetary efficient given its higher income (upper left panel). As a result of the inefficiencies introduced by the bargaining process, aggregate welfare in the union declines as asymmetry grows. Again, it is worth noting, that the loss in aggregate welfare is relatively small when asymmetry is small, but grows more than proportionally as the countries become more and more unequal (lower right panel).

Figure 2. The Effect of a Union of Two CountriesThis has troubling implications for the EU, as income asymmetry has increased with every subsequent round of expansion while the bargaining procedure for the fiscal funds has essentially stayed the same. It is not surprising then that a larger and more asymmetric EU has resulted in supranational spending that is increasingly inefficient.

The EU as a “Transfer Union”

We go on to show that the level of redistribution inherent in the Nash bargaining solution depends crucially on the overall size of the budget the union intends to raise. Increasing the EU’s budget for centralized fiscal spending would indeed lead to more “transfers” to low income members (in terms of net contributions), bringing the EU closer to the original goal of convergence. In fact, the EU could pick a budget such that inequality in terms of total welfare between member nations is completely alleviated. Such an outcome necessarily implies that the net gain from being part of the union for high-income nations is lower (albeit still positive) than for low-income members. However, this in turn has consequences for the endogenous distribution of bargaining power: Richer nations would be able to assert even more power and push even further for their own preferred projects, rendering the allocation of funds across projects less efficient. This trade-off between equality and efficiency implies that complete convergence is not necessarily socially desirable.

Arguably, this trade-off might be more important for a transition period than in the long run. If fiscal spending does not only lead to convergence in instantaneous welfare, but also has a positive effect on long-run performance and GDP growth, income asymmetries across countries will decrease even if the allocation of spending across projects is not entirely efficient. Less inequality in turn will lead to a more efficient allocation process in the future and endogenously reduce the level of necessary transfers. However, whether the growth effect of the EU’s structural funds is indeed positive remains a much-debated empirical question (see for example Becker et al. (2012)).

Institutions Fit for a Diverse Union

As the EU has expanded from the original six nations to the current 27, there has been a concurrent evolution of decision-making rules. A qualified majority rule is now used in many areas of competency. We show that the allocation of fiscal spending could also benefit from the implementation of a majority rule. Efficiency would be improved as long as the low-income member nations endogenously select into the majority coalition while their contributions to the budget remain relatively low. In connection to this, the EU might benefit from enforcing rules specifying contributions as a function of national income (such rules exist, but are easily and often circumvented), forcing wealthier member nations to pay more. An exogenous tax rule without the possibility to negotiate a discount, for example, may indeed improve overall efficiency.

It is important to note, however, that a unanimous approval of such a change is unlikely. The institutional mechanism of Nash bargaining is an “absorbing state” after the constitution stage, in the sense that not all member nations can be made better off by switching to an alternative institution. Therefore, the discussion of alternative institutions and decision making processes is particularly relevant when considering new mechanisms that increase fiscal spending at the union level, such as the proposed EU growth pact. If the same bargaining process remains to be employed even for new initiatives, even though a majority rule is preferable and implementable relative to the status quo, the opportunity for the EU to achieve efficiency in its fiscal spending is lost.

▪

References

- Becker, S. O., Egger, P and von Ehrlich, M (2012) “Too Much of a Good Thing? On the Growth Effects of the EU’s Regional Policy”, European Economic Review 56: 648 – 668

- Besley, T. and Coate, S. (2003) “Centralized versus Decentralized Provision of Local Public Goods: A Political Economy Approach” Journal of Public Economics 87: 2611 – 2637

- Boldrin, M and Canova, F (2001) ”Europé’s Regions – Income DIsparities and Regional Policies” Economic Policy 32: 207 – 253

- Delmuth, L.M. and Stoffel, M.F. (2012) “Distributive Politics and Intergovernmental Transfers: The Local Allocation of European Structural Funds” European Union Politics 13: 413 – 433

- European Commission (2014) Data available at http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/what/future/index_en.cfm

- European Movement (2010) “The EU’s Structural and Cohesion Funds” Expert Briefing, available at http://www.euromove.org.uk/index.php?id=13933

- Lockwood, B. (2002) “Distributive Politics and the Cost of Centralization” The Review of Economic Studies 69: 313 – 337

- Oates, W.E. (1972) “Fiscal Federalism” Harcourt-Brace, New York

- Pisani-Ferry, J., Marzinotto, B. and Wolff, G. B. (2011) “How European Funds can Help Greece Grow” Financial Times, 28 July 2011.

- Sala-i-Martin, X (1996) ”Regional Cohesion: Evidence and Theories of Regional Growth and Convergence”, European Economic Review 40: 1325 – 1352

- Simon, J. and Valasek, J.M. (2013) “Centralized Fiscal Spending by Supranational Unions” CESifo Working Paper No. 4321.

- Swidlicki, P., Ruparel, R., Persson, M. and Howarth, C. (2012) “Off Target: The Case for Bringing Regional Policy Back Home” Open Europe, London.

- TFEU (1957) “Treaty Establishing the European Community (Consolidated Version)”, Rome Treaty, 25 March 1957, available at: http://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b39c0.html

Trust and Economic Reforms

This brief discusses the importance of trust in economic development. In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, many countries experienced a decline in the level of both general trust and trust and confidence in the government and market institutions. Trust is important for economic growth as it facilitates economic transactions by reducing uncertainty and risk. A lack of trust in the government hinders implementation of structural reforms needed for economic development. Hence, policies aimed at rebuilding trust in the government and institutions become especially important for countries like Ukraine.

Recent events in Ukraine have highlighted an acute crisis of trust in the Ukrainian society (such as trust in the government, politicians, institutions, etc.). Over the past two decades, in the absence of a fair and transparent legal and court system, Ukrainians have become accustomed to relying on informal and often corrupt ways of living and doing business. According to a poll conducted in December 2013, less than 20 percent of the Ukrainian population said that they trust the government, police and courts.

A low level of trust in society is not, however, limited to Ukraine; this problem is also pronounced in many other parts of the world. According to the 2012 Edelman Trust Barometer survey, the general level of trust in most countries surveyed decreased compared to 2011. The most notable decline was in Brazil (36.3%), Japan (33.3%) and Spain (27.5%). These countries also experienced large drops in the level of confidence in the government: Brazil went down by 62.4%, Japan by 51% and Spain by 53.5%. According to the OECD report, generally, less than half (40%) of the citizens trust their government (OECD, 2013).

General trust is important for economic life as it reduces uncertainty and costs associated with economic transactions. Trust affects the functioning of businesses, financial markets, and government intuitions. The level of general trust varies significantly across countries (see Figure 1). While only 3.8 percent of people in Trinidad and Tobago fully trust most people, the Scandinavian countries’ share of trusting people exceeds 60 percent (Algan and Cahuc, 2013).

Economists have in their studies repeatedly appealed to the problem of trust because there are several channels through which trust may influence economic development. First, trust creates favorable conditions for long-term investment and financial market development (Algan and Cahuc, 2013). Second, a higher level of trust in various regulatory authorities increases the level of compliance with the rules and regulations if citizens believe in the fairness of such rules and regulations (Murthy, 2004). In Tabellini (2010), the level of economic development (measured by GDP per capita) of different regions of the EU member countries is compared to their level of trust (defined as in the Figure 1) and respect (defined as the proportion of people who mentioned the quality “tolerance and respect for other people” as being important). Using data from the World Value Survey rounds conducted in the 1990s, he shows that regions with a high level of trust and respect are also the regions that are the most economically developed.

In his Master thesis, the graduate of the Kyiv School of Economics Oleksii Khodenko (Khodenko 2013) analyzed the relationship between the level of trust in the government and the attitude towards market economy (in particular, the attitude towards competition and private property). For this purpose, he used data from the World Values Survey and the European Values Survey. His results have different implications for developed and less developed countries. While a lack of trust in the government in developed countries is transformed into a desire to see more market mechanisms in the economy, this mistrust of the government in developing countries (including Ukraine) undermines the faith in the entire market economy.

Khodenko’s results highlight important policy implications for transition countries: people who grew up in a centrally planned economy tend to underestimate the benefits of the free market and, therefore, only puts confidence in the government and the state as a whole to achieve the development of market mechanisms. Thus a lack of trust hinders, or even prevents implementation of structural economic reforms, which are often “painful” for some groups or for society as a whole. In countries with a low level of trust, the long-term promise of the implemented reforms to improve the lives of people is not perceived as credible. Instead of being viewed by the general public as a today’s sacrifice in the name of future prosperity, they are rather viewed as a deadweight loss (Györffy, 2013).

Figure 1. The Level of Trust in the World Source: Yann and Cahuc (2013), Figure 1.

Note: Trust is computed as the country average from responses to the trust question in the five waves of the World Values Survey (1981-2008), the four waves of the European Values Survey (1981-2008) and the third wave of the Afrobarometer (2005). The question regarding trust asks: “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that you need to be very careful in dealing with people?” Trust is equal to 1 if the respondent answers ”Most people can be trusted” and 0 otherwise.

Source: Yann and Cahuc (2013), Figure 1.

Note: Trust is computed as the country average from responses to the trust question in the five waves of the World Values Survey (1981-2008), the four waves of the European Values Survey (1981-2008) and the third wave of the Afrobarometer (2005). The question regarding trust asks: “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that you need to be very careful in dealing with people?” Trust is equal to 1 if the respondent answers ”Most people can be trusted” and 0 otherwise.

Moreover, low levels of trust affect all types of structural reforms. Elgin and Garcia (2012) show that the effect of the tax reform on the economy can significantly differ depending on the level of trust in the government; under low levels of trust the announced tax cuts do not lead to exit from the informal sector.

The question is then how to revive or rebuild trust? Knack and Zak (2003) argue that the most efficient policies for building general trust are policies that (1) reduce income inequality since people in countries with more equal income distribution tend to have higher levels of interpersonal trust, and (2) strengthen civil society to increase government accountability. Income inequality often resulting from unequal opportunities can be reduced via increases in educational attainment and income redistribution programs. The presence of a strong civil society with free press ensures that the government is accountable and responsive to its citizens. A government needs to be reliable, open and transparent to effectively address citizens’ demands (OECD, 2013). All these policies cannot be implemented without a fair legal system that guarantees equal treatment of all citizens.

▪

References

- Algan, Y. and P. Cahuc (2013) “Trust, Growth and Well-being: New Evidence and Policy Implications”, IZA Discussion Paper No. 7464

- Elgin, C. and M. Solis-Garcia (2012), “Public Trust, Taxes and the Informal Sector”, Journal Review of Social, Economic and Administrative Studies, 26(1), pp. 27-44

- Györffy, D. (2013), Institutional Trust and Economic Policy: Lessons from the History of the Euro, Central European University Press

- Knack, S. and P.J. Zak (2003), “Building Trust: Public Policy, Interpersonal Trust, and Economic Development”, Supreme Court Economic Review, 10, pp.91-107

- Khodenko, Oleksii (2013). How Does Confidence in the State Authorities Shape Pro-market Attitudes?

- Murthy, K. (2004), “The Role of Trust in Nurturing Compliance: A Study of Accused Tax Avoiders”, Centre for Tax System Integrity, Working paper No49

- OECD (2013), Government at a Glance 2013, OECD Publishing.

- Tabellini, G. (2010), “Culture and Institutions: Economic Development in the Regions of

- Europe”, Journal of the European Economic Association, 8(4), pp. 677–71

Whither Russia’s History Thought? Trends in Historical Research, Teaching and Policy-Making

The next Russian generation’s understanding of their country’s past may turn out to be more refined and complex than at present whether or not the current project of a single history-textbook and accompanying pedagogical materials are successful. Rather than imposing a new version of Stalin’s infamous ‘Short course’, as certain Western mass media predicts, the new history books will probably reflect even the most debated parts of Russia’s history from the 800s to the present, and in particular the turbulent 20th century.

Western mass media have a tendency to focus on Russian historical debates only when ‘spectacular’ and/or ‘scandalous’ events appear. For example, few news agencies paid any attention as to how the school textbooks on Russia’s contemporary history had changed through the 1990s. A whole year history classes were cancelled in the late glasnost period! This was because the Soviet-era teaching was recognized as totally outmoded in light of all the revelations on Stalinism. Starting in the mid-1990s, several groups of renowned historians produced new textbooks, history maps, and CD-ROM-materials for Russian general schools. In these pedagogical devices for children up to the final 11th class, few if any of the formerly ‘taboo questions’ remained unmentioned. By the early 2000s, a new historical landscape of Russia’s past – especially from the 1860s to the present – had appeared. Every history teacher had a number of handbooks to choose among. However, with time, it was obvious that not only did the basic ideological and political attitudes of the textbook writers influence how they presented a historical narrative. There was also a wide divergence in how even the basic facts on historical events were described.

History teaching in Russian schools has thus been highlighted in Western mass media only when a certain author has been criticized or a specific textbook lost its recommendation from the Russian Ministry of Education. Therefore, the understanding in the West, even in academic circles, of how the Russians in general have changed their perception of their country’s past is likely superficial. The obvious language barrier is only a first hindrance that explains this ignorance. The lack of knowledge of, and even an interest in, i) Russian professional historians, ii) popularizes and publicists in mass media, and iii) the general public as shown in social media describing epochs and events in the past, may also be related to a certain degree of Russophobia, traditionally present in the West.

Instead, the Western average reader tends to get his views on Russia’s Vergangenheitsbewältigung, that is its ‘coming to terms with the past’, from highly restricted analyses like Sherlock’s book (Sherlock 2007) or polemical surveys like Satter’s (Satter 2011). Sherlock investigates the glasnost debates, but ignores the changes in the 1990s and draws farfetched conclusions on the present Putin-period, based on statements by politicians. Satter concentrates on how certain leftist, pro-Stalinist opinions remain in the public sphere concerning history writing or history-memorialization with respect to the victims of state terror and repression. These two authors emphasize how politicians, rather than professional historians, have made statements, or sometimes suppressed commemorative actions on Russian history, thus creating a skewed image of how the past is analyzed in the historians’ community. In reality, there are few subjects, especially concerning the Stalinist period, that have not been investigated because of lack of sources and of non-access to archives. The remaining ‘white spots’ on the historical map concern matters that are likewise often state secrets in other states, such as military intelligence. Given how much was until 1991 classified in the archives, it is worthwhile pondering how much historians and archivists in Russia have already achieved.

The Russian professional historians’ achievements in the post-Soviet period can now be grasped easily in the solid 1,500 pages long volume, edited by one of Russia’s foremost historiographers Gennadii Bordiugov (Bordiugov 2013). Bordiugov and his colleagues have held numerous conferences since the mid-1990s where practically every new research project on all aspects of Russia’s 20th century history has been analyzed. These have been updated and collected into a massive volume. Another conference was devoted to the changing character of the historical community in general, to the research and teaching conditions in Russian universities, as well as to the interaction between historians and politicians (Bordiugov 2012). To a large extent, the economic history of Russia was until the late 1980s hampered by its rigid attachment to the Marxist and Leninist schemes of ’historical materialism’. Thus, starting during the glasnost era, Russian economic historians have made serious revisions, widespread re-interpretations and new research on practically all important stages of the evolution of the Tsarist economy, in particular concerning the early industrialization, the banking system and the entrepreneurial efforts in the 19th century. These achievements are well reflected in the two-volume encyclopedia on Russia’s economic history from oldest times till 1917, under the scientific guidance of academician and head of the Institute of Russian History of the Academy of Sciences, Iurii Petrov (Petrov 2008).

A new trend in the field is the outright proclaimed and implemented ‘history policy’ (in line with a state’s economic, social and foreign policy). Politicians strive to use their country’s past, its military feats or civilian achievements for their present purposes. This has been apparent in Russia as well as in Eastern and Western Europe, first in the wake of the collapse of the communist regimes, and then as a matter of geopolitical and socio-economic confrontation. The resolutions on 20th century history by the PACE, OSCE and other forums are examples of such history policy. Without doubt Russian publicists have also been involved in dreadful ‘wars of memory’ in particular vis-à-vis the Baltic states and Ukraine (see Borgiugov 2011b). However, among both Russian historians and certain politicians there exists a better grasp of the risks involved in history policy campaigns than seems to be the case in some East European countries. This is easily explicable, given the Russian state’s complicated thousand-year legacy of multi-cultural encounters, complex forms of conquest and expansion, social conflicts and revolutions, as well as religious and ideological controversies.

Thus, a striving towards a unified version of Russian history was reflected in the proposals by a commission set up in 2013 to formulate the ‘concept for a new, single textbook for schools on Russian history’. The initiative to substitute a multitude of textbook by a single one was set out in early 2013 in a directive from president Vladimir Putin. The original idea in Putin’s directive was to eliminate internal contradictions concerning historical events, and create a solid handbook in history with presumably straightforward, undisputable ‘facts’, just like the natural sciences can be said to have ‘a single knowledge framework’. Academicians Aleksandr Chubarian, Iurii Petrov, other historians as well as scholars from other disciplines plus politicians, led the commission. This initiative from Putin has been widely interpreted as a new stage in ‘history policy’ of the Russian government with the purpose of enforcing a new kind of patriotism or even legitimizing the allegedly ever more authoritarian present regime. However, when the concept for a single textbook was published in late autumn 2013, it became apparent that the commission had formulated a new academic, rather than a politicized framework for presenting Russia’s whole history, from the 800s to the present, with merely sketched outlines for each epoch, century of crucial decade. In over thirty appendices to the concept, leading experts describe major historical controversial questions, such as Ivan IV (‘The Terrible’), Vladimir Lenin and the 1917 Revolutions. Suffice it to mention that the appendix on the Great Terror 1937-1938 is written by Russia’s leading expert on Stalinism, professor Oleg Khlevniuk (see e.g. Khlevniuk 2008).

In early summer 2014, we can expect that the official announcement on the conditions for participation in the writing of the new textbook on Russia’s history will be announced. Just as for architectural contests, the mere presentation of a master-copy of the ‘pedagogical package’, i.e. not only the textbook but also guidelines for teachers, historical atlases, working notebooks with tasks for pupils, as well as audio and video materials will demand substantial investments from the participants’ side. Although the remuneration, in case of winning the contest, may be great, it is not expected that more than a few institutions or groups of historians will find the financial resources at hand. These proposed new textbooks will then be circulated and judged in a manner that remains to be determined.

The initial reactions in 2013 by Russian politicians and Western journalists at the appearance of the concept were skeptical. Concerns, however, were often somewhat biased. For example, in an article in ‘The Moscow Times’ the opposition politician Vladimir Ryzhkov had no objections on the first one thousand years of Russia’s history outlined in the concept. Instead, Ryzhkov lamented that the last paragraphs in the concept on Putin’s presidency had not mentioned certain oligarchs and recent dissenters. (Ryzhkov 2013). The American historian and specialist on Ukrainian history Mark van Hagen expressed his fears that Putin’s textbook would try to indoctrinate the Russian masses in a manner similar to how Stalin’s infamous ‘Short Course of the Bolshevik Party’s history’, but, of course, with a presumably new authoritarian, Orthodox Christian and multicultural Russian idea (quoted in Reuters. 2013).

It remains to be seen how much of such fears turn out to be prescient, or on the contrary, wide of the mark. Already at the official presentation in January 2014 of the commission’s result to president Putin, a number of changes in the original proposal for a single textbook were apparent. A careful reading of Putin’s speeches as well as those of Sergei Naryshkin, chairman of the Russian Historical Society and speaker of the Duma, and Academician Chubarian, scientific leader of the commission, indicate that the pedagogical package (i.e. the teacher’s handbook, textbook, map and task booklets, as well as CD-ROM and video) are likely to be much more pluralistic, as to interpreting history, than what either the initiators intended originally or what their critics presumed eventually.

Although the original idea formulated by the president himself included a phrase on giving the school children just ‘one single textbook’ (Russian: edinyi uchebnik) with new narrative, free of contradictions and contested interpretations, we can already see that even the announced concept for such a ‘single history textbook’ may well turn out to be as dynamic and thought-provoking as the real historical events were. Another alternative outcome that cannot be excluded, will be that not one single, but a few new textbooks – with different pedagogical and other highlights – will be declared as winners, provided that they reflect the new, more nuanced version of Russia’s history from oldest times to the present. In either case, these new pedagogical instruments are bound to reflect, given dozens of special surveys by experts on the debates among historians added to the concept, the achievements of archivists, professional historians and teachers in the past quarter-century. Thus, in conclusion, while substantial arguments may be raised against the political request of a single textbook on Russia’s history, the presentation of this new concept and the forthcoming contest may turn out to produce a number of excellent history teaching materials that in a wider sense will reflect both the professional historians’ achievements in recent decades, the publicists’ opinions and the expectations of the broad public.

▪

References

- Bordiugov, Gennadii, editor (2011a), Nauchnoe soobshchestvo istorikov Rossii: 20 let peremen, (Russia’s scientific community of historians: 20 years of changes), Moscow: AIRO-XXI.

- Bordiugov, Gennadii (2011b), ‘Voiny pamjati’ na postsovetskom prostranstve (‘Memory wars’ in the post-Soviet spheres), Moscow: AIRO-XXI.

- Bordiugov, Gennadii, editor (2013) Mezhdu kanunami: Isotricheskie issledovaniia v Rossii za poslednie 25 let (Between tomorrows: Historical research in Russia in the last 25 years), Moscow: AIRO-XXI.

- Khlevniuk, Oleg (2008), Master of the House, Stalin and His Inner Circle, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- President of Russia, Meeting with designers of a new concept for a school textbook on Russian history http://eng.news.kremlin.ru/news/6536accessed 2014-05-07

- Petrov, Iurii, chief editor (2008), Ekonomicheskaia istoriia Rossii s drevneishikh vremen to 1917. Entsiklopediia, Moscow: Rosspen).

- Reuters. US edition Gaabriela Baczynska ‘Putin accused of Soviet tactics in drafting new history book’ 18 November 2013, http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/11/18/us-russia-history-idUSBRE9AH0JK20131118, accessed 20140507Ryzhkov, Vladimir (2013), ‘Putin’s Distorted History’, The Moscow Times, 18 November 2013.

- Satter, David (2011) It Was a Long Time Ago, and It Never Happened Anyway: Russia and the Communist Past, New Haven. CT: Yale University Press.

- Sherlock, Thomas (2007) Historical Narratives in the Soviet Union and Post-Soviet Russia: Destroying the Settled Past, Creating an Uncertain Future, London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Skill Structure of Demand for Migrants in Russia: Evidence from Administrative Data

Authors: Simon Commander (IE Business School, EBRD and Altura Partners) and Irina Denisova (CEFIR, NES).

Using Russian Ministry of Labor administrative data for all legal migrant applications in 2010 and matching the migrant to the sponsoring firm, we find that there is some – albeit limited – evidence of firms using migrants to address high skill shortages. However, the overwhelming majority of migrants are skilled or unskilled workers rather than qualified professionals; a reflection of the low underlying rates of innovation and associated demand for high skill jobs.

Migration policy continues to be a priority in Russian economic policy. This is driven both by a demand for labor – given the unfavorable demographic trends of the last decades – and the easily available supply from the CIS countries. It is still not clear, however, what is the skills structure of the demand for migrants. Relatively new administrative data on demanded permissions to employ migrants sheds however some light on the issue.

In particular, we use the 2010 nationwide dataset ‘Job positions filled by migrants’ published by the Russia Federal Employment Service. The dataset gives detailed information on the applications for permits for migrants, including the 4-digit occupation, firm ID and the offered wage. The Federal Employment Service’s role is to approve or reject an application. In almost all cases documented in this dataset, approval was granted. Moreover, in 99% of the cases, the duration of the permitted contract was one year.

The data allow us to study the skill composition of demand for migrants from the legal sector, with the sizeable illegal labor migration staying beyond the scope of the study. The total number of applications for all of Russia in 2010 was just over 890,000, of which nearly 250,000 or 28% originated from firms in Moscow. The analysis below uses the permission data for the 21 most developed Russian regions (a full version of the paper is available as Commander and Denisova, 2012).

A breakdown of the number of requests in 2010 by skill type using the one-digit ISCO-88 classification (Managers, High-level professionals, Mid-level professionals, Service worker, Skilled agricultural workers, Craft and trades workers, Plant and machine operators, Unskilled workers) shows that over 70% of the requests were for skilled and unskilled workers. At the same time, about 17% of the total migration requests were for higher-level professionals (7%) and managers (10%). Among managers, nearly nine out of ten requests were for production or department managers with no more than 12% of managerial migration requests being for top-level executives. Among the category of high-level professionals, architects and engineers accounted for over two-fifths of requests.

Is the situation any different in the main urban labor markets? In Moscow a lower proportion – around two thirds of the migrant applications – were for skilled and unskilled workers. The starkest difference was that professionals working in IT accounted for a minute share of total high-level skill applications in Russia, but nearly 9% in Moscow. Thus, while there are some differences in the migration profile between Moscow and the rest of the country, the broad picture that emerges is one where migration policy and practice seem to be responding mainly to the apparent bottlenecks at the lower-skill end of the labor market.

Legal requests for migrants are massively dominated by requests concerning low-skill groups; and illegal migrants, as shown by anecdotal evidence, are mainly low skilled. At the same time, there is a sizeable demand for qualified migrants, managers and professionals. There are two potential motives to issuing a request for a qualified migrant: to economize on the costs of labor by substituting a local laborer with a migrant; or to fill in the gap of the scarce qualification/skills hardly available domestically. The two motives could be distinguished by looking at the wage offers associated with the posted positions and comparing them with wages paid in comparable occupations in the same region. The aim of the exercise is to see – particularly within the categories of higher-skilled applicants – whether they command any wage premium that might reflect their scarcity value.

Figures 1-2 plot the reported (relative) wage offers for two migrant skill categories: Department Managers (ISCO code=122) and Computing Professionals (ISCO code=213). The figures depict distributions of relative (to the region average) wage in logs, thus implying that the points around 0 are the wage offers at the level of regional average, above 0 means positive wage premium, and below 0 means negative wage premiums (economizing on the costs). Each figure also gives the mean search wage from the EBRD survey of recruiting agencies in 2010 (relative to the regional average).

Figure 1. Relative Wage Distribution, Production and Operation Department Managers (ISCO-88 Code: 122) Source: Authors’ calculations based on Rostrud 2010

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Rostrud 2010

It is clear from Figure 1 that the wage offers for migrants do not identify any clear positive selection effect, in that migrants’ wages mostly fall below the survey search mean comparators. In the majority of cases, the offered wages also fall below the regional average wage thus implying that the motive is to substitute for cheaper labor.

The demand for migrants with skills of IT professionals is more complicated: there are those who offer wages below regional average, but there is also a large group of those ready to pay a wage premium to attract migrants (with log wage above zero). The search through recruiting agencies (the survey wage) would still require offering higher wages.

Figure 2. Relative Wage Distribution, IT Professionals (ISCO-88 Code: 213) Source: Authors’ calculations based on Rostrud 2010

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Rostrud 2010

For further analysis, the migration dataset was mapped to the ORBIS (a dataset assembled by Bureau van Dijk) firm observations using the unique national tax identification code (so called INN). The ORBIS data includes information on firms’ balance sheets and simple performance data such as output per employee.

When looking only at demand from firms that lie in the top 10-20% of the productivity distribution (productivity is calculated as output per worker in the narrowly defined industry), the picture looks somewhat different: wage offers tend to lie above the average (Figure 3). It is likely that the most productive firms tend to offer wages higher than both regional average for the occupation and the survey-based search wages. This implies that the scarcity of skills on the domestic labor market is one of the more important motives behind the demand for migrants from high-productivity firms.

Figure 3. Relative Wage Distribution, Production and Operation Department Managers (ISCO-88 Code: 122), 10% Most Productive Firms Source: Authors’ calculations based on Rostrud 2010 and Orbis-Roslana

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Rostrud 2010 and Orbis-Roslana

To control for other firm characteristics, we run regressions relating the relative wage of a migrant to a set of firm and region characteristics, including measures of size and ownership, a measure of recent growth in the region, as well as the level and change in foreign direct investment in a given region since 2007. We also control for the tightness of the local labor market, using a measure of search wages raised in the EBRD survey compared to average wages in a region. The estimates are run with and without region, industry and occupation controls. The results show that relatively high wages tend to be associated with large and/or foreign-owned firms. Growth in a region or the level of FDI per capita are not systematically associated with the relative wage once controls enter the regression, suggesting that the relative wage is largely determined by firm-level features. The measure of labor market tightness enters positively but is insignificant whencontrolling for industry, region and occupation.

Overall, the data from the Russian Ministry of Labor that documents all applications for migrants to Russia in 2010 and allows matching the migrant to the sponsoring firm, show that there is very limited evidence of firms using migrants to fill high-skill jobs. In fact, the overwhelming majority of migrants, skilled or unskilled workers, were mostly originating from other states of the CIS. Furthermore, most were hired at relatively low wages in comparison to the occupation/region averages or the wages reported in the EBRD survey of recruiting firms. At the same time, there is a sizeable portion of demand for skilled migrants, which are offered wage premiums. The demand originates mostly from highly productive firms. Migration policy should acknowledge these different motives behind the demand for migrants.

▪

References

- Simon Commander and Irina Denisova “Are Skills a Constraint on Firms? New Evidence from Russia”, IZA Discussion Paper No. 7041, November 2012

Financial Support for Families with Children and Its Trade-Offs: Balancing Redistribution and Parental Work Incentives

Authors: Michal Myck, Anna Kurowska and Michal Kundera, CenEA.

Reforms of tax-benefit system of financial support for families with children have a broad range of consequences. In particular, they often imply trade-offs between effects on income redistribution and work incentives for first and second earners in the family. Understanding the complexity of the consequences involved in reforming family policy is crucial if the aim is to “kill two birds with one stone” namely to reduce poverty and improve incentives to work. In this brief, we illustrate these complex trade-offs by analyzing several scenarios of reforming financial support for families with children in Poland. We show that it is possible to create incentives for second earners in the family to join the labor force without destroying the work incentives of the first earners. Moreover, the same reform would allocate resources to families with lower incomes, which could result in a direct reduction of child poverty.

Financial support for families with children is an important and integral part of the broad family policy package, the goals of which fall into two basic categories of reducing child poverty and increasing labour market activity of parents (Whiteford and Adema, 2007; Björklund, 2006; Immervoll, et al., 2001). However, the particular policy aimed at one of these objectives may be detrimental to the achievement of other goals. For example, family/child benefits may directly increase family income and thus reduce child poverty. These same benefits could have a negative effect on parental incentives to work, particularly for so-called second earners, usually mothers (see e.g. Kornstad and Thoresen, 2007). However, employment of both parents often turns out to be crucial for a long-term poverty reduction (Whiteford and Adema, 2007).

The trade-offs implied by the different family policy instruments are often poorly understood or treated superficially in the policy debate. The effect of this lack of understanding may result in badly designed policy reactions to identified problems, which in turn may imply that one of the objectives is achieved at the cost of the other, or even that policies work against all of them in a longer perspective.

Using the Polish microsimulation model SIMPL, we simulate modifications of several elements of the Polish tax and benefit system to demonstrate the complex nature of trade-offs between income and employment policy, and within employment policy itself. The underlying assumption of the analysis is that any effective policy that aims at lowering child poverty in the long run ought to realize and address issues of parental labour market activities. Governments should therefore aim at a design of financial support for families to provide assistance to poor households and at the same time strong work incentives for parents.

The Polish system of support for low-income families, Family Benefits, consists primarily of Family Allowance (FA) with supplements. These are means-tested and are available to families with net incomes below 504 PLN (€121) per month and per person. The value of the FA depends on the age of the child and ranges from 68 PLN to 98 PLN (€16.40 to €23.60) per month. For eligible parents this is supplemented by additional means-tested payments to such groups as lone parents, families with more than two children, and those with school-aged children. Eligibility for Family Benefits is assessed with reference to a threshold, which once exceeded makes the family ineligible to claim the benefits. This point withdrawal of benefits implies very high effective marginal tax rates and has significant implications for average effective rates of taxes (see Myck et al., 2013). In addition to Family Benefits, financial support for families is also channelled through the tax system. Tax-splitting (joint taxation) is available to married couples and lone parents, and since 2007 parents can set their tax liabilities against the Child Tax Credit, which is a non-refundable tax credit, the maximum value of which is 1,112.04 PLN (€268) per year for every dependent child.

The starting point for our analysis, and a reference in terms of potential costs of the reform, is the move to tapered withdrawal of Family Benefits (System 1). For this purpose we use the rate of withdrawal at 55%, which is the rate used in a broadly studied in-work support programme in the UK, the Working Families’ Tax Credit (WFTC) in the late 1990s and early 2000s (see, e.g.: Blundell et al., 2000; Brewer et al., 2006; Clark et al., 2002). Application of the taper implies that with an increase of net income of 1 PLN beyond the withdrawal threshold, the total value of benefits is reduced by 0.55 PLN. Such a change would imply greater certainty and predictability of benefit receipt, compared to the current point withdrawal system. However, as it extends the availability of benefits to families who currently no longer qualify for them, it would carry additional costs. We estimate this cost to be in the range of about 1.04 billion PLN (€250mln) per year, an increase in the total value of family benefits by about 14%.

Changes in Family Benefits under System 2 involve simple increases in the values of Family Allowance, which is raised by 20% given the above cost benchmark of 1.04 billion PLN. The final reform to Family Benefits (System 3) combines introduction of the withdrawal taper (at 55%) with a bonus system for two-earner families with the specific aim of providing stronger work incentives for second earners. The bonus consists of an increase in the level of the withdrawal threshold by 50% for families where both parents work compared to the baseline threshold value.

The first reform of Child Tax Credit (System 4) assumes an increase in the value of the CTC by 19.8% (calibrated to cost same 1.04 billion PLN), while the second uses this tax credit instrument to reward two-earner status. In the latter case, double-earner couples are granted an additional value of the credit (92.70 PLN per month). The cost of this reform is again calibrated to the level of other reforms by adjusting the earnings requirement set for both parents to qualify as double-earner couples. This calibrated requirement is 2,324.50 PLN per month and per person, which is equivalent to 176.5% of the minimum wage.

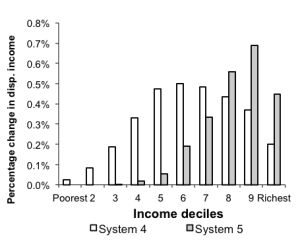

The assumptions underlying the modelled scenarios are very clearly reflected in the (static) distributional effects of the simulated changes. The proportional changes in incomes among families with children by population decile groups resulting from the simulated reforms are demonstrated in Figure 1A for Systems 1-3 and Figure1B for Systems 4-5.

Figure 1. Distributional consequences of modelled reforms: Proportional changes in incomes of families with children by income deciles.

Source: Authors’ calculations using the SIMPL microsimulation model on PHBS 2010 data.

Source: Authors’ calculations using the SIMPL microsimulation model on PHBS 2010 data.

Figures 2 and 3 show how the modelled reforms would affect incentives to work for first and second earners measured as average changes in replacement rates[1] (RRs) by centiles of the baseline distribution of replacement rates for modelled families. The RR for the first earner is the ratio of the family income when neither partners work and the family income when the first earners works full time. The RR for the second earner is the ratio of the family income when only first earners work and the family income when both partners work full time. Lowest values of RRs imply the strongest incentives and highest values reflect the weakest incentives to work. When the difference in RR between the Baseline and a particular System is greater than zero it implies that this System increases incentives to work for a particular earner compared to the Baseline. This approach provides evidence on the trade-off between improving work incentives for those facing strong and weak incentives in the baseline system. The pattern that emerges from Figures 2 and 3 reflects to some extent the distributional effects of the chosen reforms (Figure 1). This is because richer families are usually those with high labour market incomes and thus low RRs (high labour market incentives), while poorer families face weaker incentives given their low actual (or potential) earnings, and thus face higher replacement ratios.

Figure 2. Changes in RRs by baseline work incentives – first earners Source: Authors’ calculations using the SIMPL microsimulation model on PHBS 2010 data.

Notes: Based on a sample of couples with children. System 5 does not change first earner incentives.

Figure 3. Changes in RRs by baseline work incentives – second earners

Source: Authors’ calculations using the SIMPL microsimulation model on PHBS 2010 data.

Notes: Based on a sample of couples with children. System 5 does not change first earner incentives.

Figure 3. Changes in RRs by baseline work incentives – second earners

Source: Authors’ calculations using the SIMPL microsimulation model on PHBS 2010 data.

Notes: Based on a sample of couples with children.

Source: Authors’ calculations using the SIMPL microsimulation model on PHBS 2010 data.

Notes: Based on a sample of couples with children.

Apart from the well-established trade-off between equity and labour market concerns, our paper draws attention to the need to balance out first and second earner work incentives as well as incentives by the degree of existing financial motivation to work.

Reforms at the two extremes of the distributional spectrum, namely an increase in the level of Family Benefits (System 2) and a Child Tax Credit bonus for two-earner couples (System 5), result in very different incentive effects. The former significantly weakens incentives of both first and second earners in couples, while the second, which specifically directs resources at second earners, produces important improvements in incentives to work for second earners. However, these gains focus on the part of the spectrum of the baseline distribution of work incentives where these are already strong. This contrasts with a reform in which a two-earner “bonus” is created as part of Family Benefits (System 3). This system increases the generosity of in-work support for first earners in couples in a similar way to the benchmark reform. At the same time, however, it improves the attractiveness of work for second earners by raising the level of income from which benefits are withdrawn for couples in which both partners are working.

This arrangement balances out the negative influence on second earner incentives of the income effect of making work more financially attractive for first earners, which does not happen under our benchmark scenario (System 1). Moreover, we demonstrate that trying to increase work incentives through higher levels of Child Tax Credit available to families would have a positive effect on the work incentives of a large number of families, in particular on first earners in couples. The flip side of this effect would be some negative incentive effects on second earners, but generally both types of effect would be very low given the assumed cost restriction of the modelled reforms.

Naturally, there is an endless number of ways in which a billion PLN can be spent on families with children. As we argued above, each type of reform will have a complex set of consequences on household incomes and incentives to work for parents. The breakdown of employment pattern in Poland suggests that to increase labour market activity, the family support policy should focus on trying to make work pay for second earners in couples, most of whom are women. As we demonstrated this can be done in such a way as to balance out incentives for first earners and provide strong incentives to those second earners who currently face the weakest incentives to work. At the same time, resources would be directed to families in the lower half of income distribution that could result in direct reduction of child poverty.

▪

References

- Blundell R., A. Duncan, J. McCrae and C. Meghir (2000) The Labour Market Impact of the Working Families’ Tax Credit, Fiscal Studies, vol. 21(1), pp. 75-104.

- Brewer M., A. Duncan, A. Shephard and M.-J. Suarez (2006) “Did Working Families’ Tax Credit Work? The Impact of In-Work Support on Labour Supply in Great Britain”, Labour Economics, vol. 13, pp. 699-720.

- Björklund A. (2006) Does family policy affect fertility? Journal of Population Economics, vol. 19 (1), pp. 3-24.

- Clark T., A. Dilnot, A. Goodman, and M. Myck (2002) Taxes and Transfers, Oxford Review of Economic Policy, vol.18 (2), pp. 187-201.

- Immervoll H., H. Sutherland, K. de Vos (2001) Reducing child poverty in the European Union: the role of child benefits, in: Vleminckx K. and Smeeding T.M. (eds) Child well-being, Child poverty and Child Policy in Modern Nations. What do we know? Revised Edition; The Policy Press: Bristol.

- Kornstad T. and T. O. Thoresen (2007) A Discrete Choice Model for Labor Supply and Child Care, Journal of Population Economics, vol. 20 (4), pp. 781-803.

- Myck, M., A. Kurowska, and M. Kundera (2013) “Financial Support for Families with Children and its Trade-offs: Balancing Redistribution and Parental Work Incentives”, Baltic Journal of Economics, 13(2), 59-84.

- Whiteford P. and W. Adema (2007) What Works Best in Reducing Child Poverty: A Benefit of Work strategy? OECD Social, Employment and Migration Woking Papers, nr 51, OECD, Paris.

[1]For the couples in the subsample we compute three sets of family-level incomes, conditional on employment either of the first earner (who is the person with higher expected earnings in a couple) or of both partners; Y(1,1) for the scenario where both partners are employed (full-time); Y(1,0) for the scenario where the first earner is employed (full-time); Y(0,0) for the scenario where both partners are not employed. This allows us to compute replacement ratios for the first earner (RR1) and the second earner (RR2) for each of the analysed tax and benefit systems (S): RR1(s,j)=Y(s,j)(0,0)/Y(s,j)(1,0) and RR2(s,j)=Y(s,j)(1,0)/Y(s,j)(1,1).

What Expansion of Mandatory Schooling Can and Cannot Do in Conservative Muslim Societies

New research shows expanding mandatory schooling in conservative Muslim societies have broad positive effects on female empowerment but is not enough to overcome the significant barriers to female entry in the labor force.

Does expansion of public education empower women? A large literature documents the positive effects of education on women’s economic and social outcomes in developed countries, but we know less about its causal effects on women’s empowerment in Muslim societies where women’s participation in the labor market is limited and they often do not have control over their earnings or their own bodies (Doepke et al 2012). In fact, even though female education has been successfully expanding in many majority-Muslim countries, the number of legal rights enjoyed by women is few relative to men, and female labor-force participation remains low (UNDP 2005). The lack of a corresponding labor-force participation effect raises concerns over the efficacy of expanding education as a means of improving women’s rights in Muslim societies. On the other hand, education has been shown to have many important non-pecuniary effects outside the labor market, such as in health, marriage, and parenting style (Oreopolous and Salvanes 2011) and to the extent that these effects help empower women, they may constitute alternative mechanisms through which education may lead to women’s empowerment (even in the absence of large labor market returns). However, most of this research comes from countries and societies that are not majority-Muslim and where women do work to a larger degree. As such, disentangling non-pecuniary returns to education from its labor market (and thus pecuniary) returns is particularly challenging in most settings and whether education may empower women in the Muslim world remains an open question.

Even though scholars debate the fundamental causes for the severe degrees of gender inequality in Muslim societies, most posit a nexus of patriarchal culture, strong religious values, and restricting social norms as proximate explanatory factors. Historically, Lewis (1961) claims women’s status was “probably the most profound single difference” between Muslim and Christian civilizations. In more contemporary cross-country studies, Fish (2002) documents a negative cross-country correlation between having an “Islamic religious tradition” and female empowerment, while Barro and McCleary (2006) also show that Muslim countries tend to exhibit higher degrees of religious participation and beliefs. Comparing the effects of a business training program on female entrepreneurship among Hindu and Muslim women in India, Field et al (2010) find evidence in line with significantly stricter constraints to female labor-force participation among Muslim women. To the extent that barriers to entry due to religious values restrain women’s rights, an integral outcome of empowerment is therefore a woman’s ability to independently assert her own beliefs.

In a recent paper, Selim Gulesci and I exploit an extension of compulsory schooling in Turkey to estimate the causal effect of schooling on female empowerment (Gulesci and Meyersson 2014). Compulsory schooling laws have been extensively used to estimate returns to education in Western countries on labor market outcomes (Angrist and Krueger, 1991, Oreopoulos 2006), health and fertility (McCrary and Royer 2011, Lleras-Muney 2005, Black et al 2008) among others. We follow a similar strategy to provide meaningful causal parameters for the effect of a year of schooling on outcomes related to social status of women in Turkey, a majority-Muslim country.

In 1997, Turkey’s parliament passed a new law to increase compulsory schooling from 5 to 8 years. By this law, individuals born on or after September 1986 were bound to complete 8 years of schooling, whereas those born earlier could drop out after 5 years. Using the sample of ever-married women from the 2008 Turkish Demographic Health Survey (TDHS) we are able to observe outcomes 10 years after the law change was implemented.

We adopt a regression discontinuity (RD) design assigning treatment based on whether an individual’s month-and-year of birth was before or after the September 1986 threshold. As such, our identification strategy entails comparing cohorts born one month apart and relies on the assumption that these two groups should exhibit no systematic differences other than being subject to different compulsory schooling laws. We can thus calculate an RD treatment effect, illustrative of the causal effect of education for individuals born around the threshold.

Analysis of the sample of ever-married women focuses the RD treatment effects on a subset of the population that tends to be demonstratively poorer and more socially conservative, i.e. the very subpopulation that the reform was aimed at. In a comparison of ever- and never-married women, the reform only affected education among the former, and as a result, the exclusion of non-married women effectively means exclusion of non-compliers with the reform. This is a likely consequence of ex post single women being more likely to have attended school longer regardless of expanding reforms. We also show that the probability of selection into the married sample is not affected by the law.

Our results are as follow. First, we show the effect of the reform on women’s years of schooling. As a result of the reform, women’s average years of schooling increased by one year, and completion rates for junior-high (secondary) and high school completion increased by 24 and 8 percentage points (ppt) respectively. There is no significant impact of the reform on men’s schooling on average (mainly because the average man’s schooling in Turkey around the age threshold was already at a relatively high level). Thus, the reform effectively served to reduce the education gender gap by half.

Second, our RD estimates reveal that this additional year of schooling had significant secularizing effects. Ten years after the reform was implemented, and relative to sample means, women were 10 percent (8 ppt) less likely to wear a headscarf, 22 percent (10 ppt) less likely to have attended a Qur’anic study center and 18 percent (7 ppt) less likely to pray regularly.

Third, we find no evidence of schooling on the timing of either marriage or birth, nor on the number of children. We do however find significant effects on women’s decision rights with regards to both marriage and fertility decisions; a reform-induced year of schooling results in a 10 ppt (20 percent relative to the sample mean) increase in the likelihood of having a say in the marriage decision, and a 10 ppt (12 percent) increase in the likelihood of having a say in the type of contraceptive method adopted. We further find a reducing effect of schooling on the likelihood that a bride price was received by the women’s parents from their husband’s family upon their wedding.

Fourth, we document less pronounced and largely imprecise impacts on women’s labor market outcomes. Although our estimates indicate positive effects on non-agricultural employment in general, and self-employment in particular, these estimates are sensitive to the specification used. At the same time, we show significant positive effects of schooling on household wealth, largely driven by appliances related to women’s role as housewives. We are unable to explain this by observable increases in spousal quality, measured as husband’s years of schooling.

Altogether, our results indicate significant empowering effects of education, but whereas we document precise effects on decision rights, household wealth, and measures of social and religious conservatism, we fail to find equally concise effects on spousal and labor force outcomes. This prevents an interpretation relying exclusively on either labor market or assortative matching in the marriage market as the main channel of empowerment. In fact, an examination of heterogeneous effects reveal diverging effects depending on how socially conservative women’s backgrounds are; in rural areas, education pre-dominantly allows increased freedom to be more secular, greater decision rights over marriage, and less traditional marriages. In urban areas, education has similar effects, but also leads to increased labor force participation. We interpret this as increased education, and its associated bargaining power in the household, leading to different allocations depending on the preexisting level of women’s rights. Education may thus have only a partial effect on employment, as religious or cultural barriers to entry prevent women from realizing larger gains of education through the labor market.

Our paper adds to the research literature by providing meaningful causal parameters for the effect of a year of schooling on both social and religious outcomes for women in a majority-Muslim country. The findings point to a set of returns to schooling that take into context the socially conservative nature of the Turkish society where policies to increase schooling ultimately seem to improve women’s status (as captured by higher decision-making power and household wealth) but are unable to meaningfully break down the barriers that women face in entering the labor market, particularly in more conservative rural communities. While still having important empowerment consequences for women’s empowerment in Muslim societies, education may not be a magic bullet toward full emancipation. Policies hoping to achieve female empowerment will thus require complementary reforms in health and the labor market to address barriers to entry more directly.

References

- Denisova, I., and S.Commander, S.Commander and I. Denisova (2012), ‘Are skills a constraint on firms? New evidence from Russia’, EBRD and CEFIR/NES, mimeo

- Hausmann, R., and Klinger, B., (2007), “The Structure of the Product Space and the Evolution of Comparative Advantage”, CID Working Paper No. 146

- Volchkova, N., Output and Export Diversification: evidence from Russia, CEFIR Working Paper, 2011

- Angrist, Joshua D. and Alan. B. Krueger, 1991, “Does Compulsory Schooling Attendance Affect Schooling and Earnings?” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106(1): 979-1014.

- Barro, Robert and Rachel McCleary, 2006, “Religion and Economy”, Journal of Economic Per- spectives, 20(2): 49-74.

- Black, Sandra, Paul Devereux, and Kjell G. Salvanes, 2008, “Staying in the Classroom and out of the Maternity Ward? The Effect of Compulsory Schooling Laws on Teenage Births”. Economic Journal, 118(530): 1025-54.

- Doepke, Matthias, and Michelle Tertilt, 2009, “Women’s Liberation: What’s in it for Men?”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124: 1541-91.

- Field, Erika, Seema Jayachandran and Rohini Pande, 2010, “Do Traditional Institutions Constrain Female Entrepreneurial Investment? A Field Experiment on Business Training in India”, American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings, 100: 125-29.

- Gulesci, Selim, and Erik Meyersson, 2014, “For the Love of the Republic – Education, Secularism, and Empowerment”, working paper.

- Lewis, Bernard, 1961, “The Emergence of Modern Turkey”, Oxford University Press: London.

- McCrary, Justin, 2008, “Manipulation of the Running Variable in the Regression Discontinuity

- Design: A Density Test,” Journal of Econometrics, 142(2): 698-714.

- Lleras-Muney, Adriana, 2005, “The Relationship between Education and Adult Mortality in the United States,” Review of Economic Studies, 21(1): 189-221.

- Oreopolous, Phillip, 2006, “Estimating Average and Local Average Treatment Effects of Education when Compulsory Schooling Laws Really Matter ”, American Economic Review, 96(1): 152-175.

- Oreopolous, Philip and K. G. Salvanes, 2011, “Priceless: The Nonpecuniary Benefits of Schooling”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 25(1): 159-184.

- UNDP, 2005, “Arab Human Development Report 2005 – Towards the Rise of Women in the Arab World”.

Macroeconomic Performance and Preferences for Democracy

This policy brief summarizes the results of our research on factors influencing preferences for democracy in transition countries. The aim of this work was to detect which macroeconomic and individual factors impact the choice of supporting democracy. The results showed that the performance of the country, described by level of GDP, unemployment, level of corruption and economic growth, has a serious impact on an individual’s perception of democracy. At the same time, individual factors like education and age also influence people’s choice of support of democratic authorities.

Individual perception of democracy is a question that attracts the attention of policymakers. The macroeconomic instability that has been observed worldwide lately is likely to impact individual attitude toward democratic values and political institutions. The recent economic crisis brought a deterioration of the economic situation around the world and provided new challenges to cope with. It is likely that macroeconomic indicators have an impact on how a person perceives democracy. Literature studying similar questions has shown that GDP growth, unemployment and inflation all affect personal attitude to democratic institutions (Clarke et. al., 1994; Barro, 1999; Papaioannou and Siourounis, 2008). As for individual characteristics, the level of education is revealed by the literature as a very important factor in the context of the individual’s propensity of democracy approval.

The literature on the determinants of political support and attitudes to democracy was mostly focusing on exploring stable world economies with long-formed and steady-functioning democracies. We tried to look at a similar question in the context of transition economies, where democratic institutions are still under development.

We intend to estimate individuals’ propensity to favor democratic values. The specification of our econometric model was based on the literature addressing the same topic. The estimation procedure used probit econometric techniques, which allows for the calculation of the propensities of interest while taking into account the influence of both macroeconomic factors and individual characteristics. The paper used two sources of data: macroeconomic information was collected from the World Development Indicators of the World Bank, and individual-level cross-sectional data was obtained from Life in Transition Survey (LITS) 2010, which initially covered 38864 individuals from 35 countries. However, as the paper focuses on countries in transition, the final set only included individuals from 30 countries, most from Eastern Europe, Baltics and CIS, and excluded representatives of Western Europe. This data allowed for substantial data variation in the context of economic development vs. perception of democratic values (Graph 1).

Figure 1. Support of Democracy and GDP Per Capita Source: WDI and LITS 2010

Source: WDI and LITS 2010

Inclusion of different macroeconomic variables together with individual factors allowed for an evaluation of their importance and level of impact on the perception of democratic values (Table 1). The results show that GDP per capita has a positive and significant effect on individuals’ perception of democratic values, which is in line with the literature claiming that standard of living in countries with not so high level of GDP is positively correlated with satisfaction with their life and the political system (Easterlin, 1995; Clark et al., 2008; Stevenson and Wolfers, 2008). Inflation rates are not significant and do not influence individuals’ attitude to democracy. On the other hand, economic growth is strictly positive and significant, and an increase of the economic growth rate raises propensity of democratic support by around 1.6 percentage points. The possible explanation here is that the growth rate of GDP works as a proxy of expectations for improvements of the standard of living in the future.

Table 1. Influence of Macroeconomic and Individual Factors on Perception of Democracy

Unemployment works as an indicator of a country‘s economic performance and has an expected negative sign in terms of individuals’ satisfaction with life and political institutions, which is also in line with the results in the literature (Di Tella et al., 2001; Wagner and Schneider, 2006). Impact of unemployment was tested using a cross product of unemployment and the Freedom House Index (this latter indicator shows the level of political and civil rights from 1 (most free) to 7 (least free)). The sign on this cross product is positive, which captures their mutual positive impact on the support for democracy. Thus, the higher the unemployment in a country with a low level of democratization is, the larger the probability of democratic support by individuals in these countries is. The indicator for the level of corruption in a country was also taken into account, via the Corruption Perception Index. This index ranks countries on a scale from 0 (highly corrupt) to 10 (effectively, corruption-free). The results show that the less corrupt a country is, the higher the propensity that an individual in that country will support democracy is. In fact, one additional point in the index increases the propensity of support by almost 4 percentage points. Military expenditures negatively affect the support of democratic values, and so does the existence of oil in the country. Here, military expenditures may be seen as a proxy for a less democratic regime, so that the leaders there have higher incentives to rule using suppressive measures with a support of military force in the country (Mulligan, Gil and Sala-i-Martin, 2004).