Tag: financial support

Ukraine’s Fight Is Our Fight: The Need for Sustained International Commitment

We are at a critical juncture in the defense of Ukraine and the liberal world order. The war against Ukraine is not only a test of Europe’s resilience but also a critical moment for democratic nations to reaffirm their values through concrete action. This brief examines Western support to Ukraine in the broader context of international efforts, putting the order of magnitudes in perspective, and emphasizing the west’s superior capacity if the political will is there. Supporting Ukraine to victory is not just the morally right thing to do, but economically rational from a European perspective.

As the U.S. support to the long-term survival of Ukraine is becoming increasingly uncertain, European countries need to step up. This is a moral obligation, to help save lives in a democratic neighbor under attack from an autocratic regime. But it is also in the self-interest of European countries as the Russian regime is threatening the whole European security order. A Russian victory will embolden the Russian regime to push further, forcing European countries to dramatically increase defense spending, cause disruptions to global trade flows, and generate another wave of mass-migration. This brief builds on a recent report (Becker et al., 2025) in which we analyze current spending to support Ukraine, put that support in perspective to other recent political initiatives, and discuss alternative scenarios for the war outcome and their fiscal consequences. We argue that making sure that Ukraine wins the war is not only the morally right thing to do, but also the economically rational alternative.

The International Support to Ukraine

The total support provided to Ukraine by its coalition of Western democratic allies since the start of the full-scale invasion exceeded by October 2024 €200 billion. This assistance, which includes both financial, humanitarian, and military support, can be categorized in various ways, and its development over time can be analyzed using data compiled by the Kiel Institute for the World Economy. A summary table of their estimates of aggregate support is provided below.

A particularly relevant aspect in light of recent news is that approximately one-third of total disbursed aid has come from the United States. The U.S. has primarily contributed military assistance, accounting for roughly half of all military aid provided to Ukraine. In contrast, the European Union—comprising both EU institutions and bilateral contributions from member states—stands as the largest provider of financial support. This financial assistance is crucial for sustaining Ukraine’s societal functions and maintaining the state budget.

Table 1. International support to Ukraine, Feb 2022 – Oct 2024

Source: Trebesch et al. (2024).

Moreover, the EU has signaled a long-term commitment to provide, in the coming years, an amount comparable to what has already been given. This EU strategy ensures greater long-term stability and predictability, guaranteeing that Ukraine has reliable financial resources to sustain state operations in the years ahead. Consequently, while a potential shift in U.S. policy regarding future support could pose challenges, it would not necessarily be insurmountable.

What is crucial is that Ukraine’s allies remain adaptable, and that the broader coalition demonstrates the ability to adjust its commitments, as this will be essential for sustaining the necessary level of assistance moving forward.

Putting the Support in Perspective

To assess whether the support provided to Ukraine is truly substantial, it is essential to place it in context through meaningful comparisons. One approach is to examine it in historical terms, particularly in relation to past instances of large-scale military and financial assistance. A key historical benchmark is the Second World War, when military aid among the Allied powers played a decisive role in shaping the outcome of the conflict. Extensive resources were allocated to major military operations spanning multiple continents, with the United States and the United Kingdom, in particular, dedicating a significant share of their GDP to support their allies, including the Soviet Union, France, and other nations. As seen in Figure 1, by comparison, the current level of aid to Ukraine, while substantial and essential to its defense, remains considerably smaller in relation to GDP.

Figure 1. Historical comparisons

Source: Trebesch et al. (2024).

Another way to assess the scale of support to Ukraine is by comparing it to other major financial commitments made by governments in response to crises. While the aid allocated to Ukraine is significant in absolute terms, it remains relatively modest when measured against the scale of other programs, see Figure 2.

A recent example is the extensive subsidies provided to households and businesses to mitigate the impact of surging energy prices since 2022. Sgaravatti et al. (2021) concludes that most European countries implemented energy support measures amounting to between 3 and 6 percent of GDP. Specifically, Germany allocated €157 billion, France and Italy each committed €92 billion, the UK spent approximately €103 billion. These figures represent 5 to 10 times the amount of aid given to Ukraine so far, with some countries, such as Italy, allocating even greater relative sums. On average, EU countries have spent about five times more on energy subsidies than on Ukraine aid. Only the Nordic countries and Estonia have directed more resources toward Ukraine than toward energy-related support. Although not all allocated funds have been fully disbursed, the scale of these commitments underscores a clear political and financial willingness to address crises perceived as directly impacting domestic economies.

Figure 2. EU response to other shocks (billions of €)

Source: Trebesch et al. (2024).

Another relevant comparison is the Pandemic Recovery Fund, also known as Next Generation EU. With a commitment of over €800 billion, this fund represents the EU’s comprehensive response to the economic consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic. Again, the support to Ukraine appears comparatively small, about one seventh of the Pandemic Recovery Fund.

The support to Ukraine is also much smaller in comparison to the so-called “Eurozone bailout”, the financial assistance programs provided to several Eurozone member states (Greece, Ireland, Spain and Portugal) during the sovereign debt crisis between 2010 and 2012. The programs were designed to stabilize the economies hit hard by the crisis and to prevent the potential spread of instability throughout the Eurozone.

Overall, the scale of these commitments underscores a clear political and financial willingness and ability to address crises perceived as directly impacting domestic citizens. This raises the question of whether the relatively modest support for Ukraine reflects a lack of concern among European voters. However, this does not appear to be the case. In survey data from six countries – Belgium, Germany, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, and Poland – fielded in June 2024, most respondents express satisfaction with current aid levels, and a narrow majority in most countries even supports increasing aid (Eck and Michel, 2024).

A further illustration comes from the Eurobarometer survey conducted in the spring of 2024 which asked: “Which of the following [crises] has had the greatest influence on how you see the future?”. Respondents could choose between different crises, including those mentioned above, and the full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Figure 3 illustrates the total commitments made by EU countries for Ukraine up until October 31, 2024, compared to other previously discussed support measures, represented by the blue bars. The yellow bars, on the other hand, show a counterfactual allocation of these funds, based on public priorities as indicated in the Eurobarometer survey. Longer yellow bars indicate that a higher proportion of respondents perceived this crisis as having a greater negative impact on their outlook for the future. By comparing the actual commitments (blue bars) with this hypothetical allocation (yellow bars)—which reflects how resources might have been distributed if they aligned with the population’s stated priorities—it becomes evident that there is substantial public backing for maintaining a high level of support for Ukraine. The results show that the population prioritizes the situation in Ukraine above several other economic issues, including those that directly affect their own personal finances.

Figure 3. Support to Ukraine compared to other EU initiatives – what do voters think?

Source: Trebesch et al. (2024); Niinistö (2024); authors’ calculations.

The Costs of Not Supporting Ukraine

When discussing the costs of support to Ukraine it is important to understand what the correct counterfactual is. The Russian aggression causes costs for Europe irrespective of what actions we take. Those costs are most immediately felt in Ukraine, with devastating human suffering, the loss of lives, and a dramatic deterioration in all areas of human wellbeing. Also in the rest of Europe, though, the aggression has immediate costs, in the economic sphere primarily in the form of dramatically increased needs for defense spending, migration flows, and disruptions to global trade relationships. These costs are difficult to determine exactly, but they are likely to be substantially higher in the case of a Russian victory. Binder and Schularik (2024) estimate increased costs for defense, increased refugee reception and lost investment opportunities for the German industry at between 1-2 percent of GDP in the coming years. As they put it, the costs of ending aid to Ukraine are 10-20 times greater than continuing aid at Germany’s current level.

Any scenario involving continued Russian aggression would demand substantial and sustained economic investments in defense and deterrence across Europe. Clear historical parallels can be drawn looking at the difference in countries’ military spending during different periods of threat intensity. Average military spending in a number of Western countries during the Cold War (1949-1990) was about 4.1 percent of GDP, much higher in the U.S. but also in Germany, France and the UK. In the period after 1989-1991 (the fall of the Berlin Wall, the dissolution of the Soviet Union), the amounts fell significantly. The average for the same group of countries in this period is about 2 percent of GDP and only 1.75 percent if the U.S. is excluded.

Also after 1991 there is evidence of how perceived threats affect military spending. Figure 4 plots the change in military spending over GDP between 2014-2024 against the distance between capital cities and Moscow. The change varies between 0 (Cyprus) and around 2.25 (Poland) and shows a very clear positive correlation between increases in spending and proximity to Moscow. There has also in general been a substantial increase in military spending after 2022 in several European countries, but in a scenario where Russia wins the war, these will certainly have to be increased further and maintained at a high level for longer. An increase in annual military expenditure in relation to GDP in the order of one to two percentage points would mean EUR 200-400 billion per year for the EU, while the total EU support to Ukraine from 2022 to today is just over €100 billion.

Figure 4. Increase in military expenditures in relation to distance to Moscow

Source: SIPRI data, authors’ calculations.

A Russian victory would also have profound consequences for migration flows, with the most severe effects likely in the event of Ukraine’s surrender. The Kiel Institute estimates the cost of hosting Ukrainian refugees at €26.5 billion (4.2 percent of GDP) for Poland, one of the countries that received the largest flows. Beyond migration, a Russian victory would also reshape the global geopolitical order. Putin has framed the war as a broader conflict with the U.S. and its democratic allies, while an emerging alliance of Russia, Iran, North Korea, and China is positioning itself as an alternative to the Western-led system. A Ukrainian defeat would weaken the authority of the U.S., NATO, and the rules-based international order, potentially driving more nations in the Global South toward authoritarian powers for military and economic support. This shift could disrupt global trade, affect access to food, metals, and energy. Estimating the full economic impact of such a shift is difficult, but comparisons can be drawn with other global shocks. The European Union’s GDP experienced a significant contraction due to the Covid-19 pandemic, 5.9 percent contraction in real GDP according to Eurostat, 6.6 percent according to the European Central Bank. While the economy rebounded relatively quickly from the pandemic, a permanent geopolitical realignment caused by a Russian victory would likely have far more severe and lasting economic consequences.

Given that Ukraine is at the forefront of Russia’s aggression, its resilience serves as a critical test of Europe’s ability to withstand potential future threats. Thus, strengthening our own security and economic stability in the long term is inseparable from strengthening Ukraine’s resilience now. The fundamental difference lies in the long-term trajectory of these investments. In a scenario where Ukraine is victorious, military and financial aid during the war would eventually transition into reconstruction efforts and preparations for the country’s integration into the EU. This outcome is undeniably more favorable—both economically and in humanitarian terms—not only for Ukraine but for Europe as a whole. Therefore, an even more relevant question is whether the level of support is enough for Ukraine to win the war.

Is Sufficient Support Feasible?

Is it even reasonable to think that we in the West could be able to support Ukraine in such a way that they can militarily defeat Russia? Russia is spending more on its war industry than it has since the Cold War. In 2023, it spent about $110 billion (about 6 percent of GDP). By 2024, this figure is expected to have increased to about $140 billion (about 7 percent of GDP). These amounts are huge and represent a significant part of Russia’s state budget, but they are not sustainable as long as sanctions against Russia remain in place (SITE, 2024). For the EU, on the other hand, the sacrifices needed to match this expenditure would not be as great. The EU’s GDP is about ten times larger than Russia’s, which means that in absolute terms the equivalent amount is only 0.6-0.7 percent of the EU’s GDP. If the U.S. continues to contribute, the share falls to below 0.3 percent of GDP.

Despite the economic advantage of Ukraine’s allies over Russia, several factors could still shift the balance of power in Russia’s favor. One key issue is military production capacity—Russia has consistently outproduced Ukraine’s allies in ammunition and equipment. While Western economies have the resources to manufacture superior weaponry, actual production remains insufficient, requiring both increased capacity and political will. Another challenge is cost efficiency. Military purchasing power parity estimates suggest that Russia can produce approximately 2.5 times more military equipment per dollar than the EU, giving it a cost advantage in volume production. However, this does not fully compensate for its overall economic disadvantage, particularly when factoring in quality differences.

Manpower is also a critical factor. Russia’s larger population allows for sustained mobilization, but at a steep financial cost. Soldiers are recruited at a minimum monthly salary of $2,500, with additional bonuses bringing the first-year cost per recruit to three times the average Russian annual salary. Compensation for injured and fallen soldiers further strains state finances, with estimated payouts reaching 1.5 percent of Russia’s GDP between mid-2023 and mid-2024. Over time, these costs limit Russia’s ability to fund its war effort, making mass mobilization financially unsustainable.

Overall, advanced Western weaponry and superior economic capacity can match Russia’s advantage in manpower if the political will is there. Additionally, Russia’s already fragile demographic situation is deteriorating due to battlefield losses and wartime emigration. Any measure that weakens Russia’s economic capacity—particularly through sanctions and embargoes—diminishes the strategic advantage of its larger population and serves as a crucial complement to military and financial support for Ukraine.

Conclusion

Ukraine’s western allies have provided the country with substantial military and financial support since the onset of the full-scale invasion. Yet, relative to the gravity of the risks involved, previous responses to economic shocks, and citizens’ concerns about the situation, the support is insufficient. The costs of a Russian victory will be higher for Europe, even disregarding the human suffering involved. With U.S. support potentially waning, EU needs to pick up leadership.

References

- Becker, Torbjörn; and Anders Olofsgård; and Maria Perrotta Berlin; and Jesper Roine. (2025). “Svenskt Ukrainastöd i en internationell kontext: Offentligfinansiella effekter och framtidsscenarier”, Commissioned by the Swedish Fiscal Policy Council.

- Binder, J. & Schularick, M. (2024). “Was kostet es, die Ukraine nicht zu unterstützen?” Kiel Policy Brief No. 179.

- Eck, B & Michel, E. (2024). “Breaking the Stalemate: Europeans’ Preferences to Expand, Cut, or Sustain Support to Ukraine”, OSF Preprints, Center for Open Science.

- Niinistö, S. (2024) .“Safer Together – Strengthening Europe’s Civilian and Military Preparedness and Readiness” European Commission Report.

- Sgaravatti, G., S. Tagliapietra, C. Trasi and Zachmann, G. (2021). “National policies to shield consumers from rising energy prices”, Bruegel Datasets, first published 4 November 2021.

- SITE. (2024). “The Russian Economy in the Fog of War”. Commissioned by the Swedish Government.

- Trebesch, C., Antezza, A., Bushnell, K., Bomprezzi, P., Dyussimbinov, Y., Chambino, C., Ferrari, C., Frank, A., Frank, P., Franz, L., Gerland, C., Irto, G., Kharitonov, I., Kumar, B., Nishikawa, T., Rebinskaya, E., Schade, C., Schramm, S., & Weiser, L. (2024). “The Ukraine Support Tracker: Which countries help Ukraine and how?” Kiel Working Paper No. 2218. Kiel Institute for the World Economy.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in policy briefs and other publications are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect those of the FREE Network and its research institutes.

Can Farmland Market Liberalization Help Ukraine in its Reconstruction and Recovery?

The Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine has inflicted massive damage and losses on Ukraine, already amounting to more than 2.5 times Ukraine’s 2023 GDP. Despite substantial and continuing international political and financial support to help Ukraine in its recovery and reconstruction, it is becoming increasingly clear that it will need to mobilize its own resources and private financing as well – not just for the country’s reconstruction but also for its long-term development. From a government perspective, it is important for Ukraine to leverage scarce public and donor resources and to undertake necessary reforms to facilitate and crowd in private financing. Farmland market liberalization is one of the key reforms in this respect. Its scale, with farmland accounting for more than 70 percent of Ukraine’s territory, and capacity for private financing generation for agriculture and rural areas, is, however, often underestimated.

An Unbearable War Toll and the Need for Private Financing

The raging Russian war on Ukraine enters its third year, imposing an immense toll in terms of human life, economic stability, and regional security. About 20 percent of Ukraine’s territory has been occupied. More than 10 million Ukrainians have left their homes, including 6.45 million refugees that have resettled across Europe (UNHCR, 2024). Ukraine’s military casualties are reported to be approaching 200,000 (The New York Times, 2023) and at least 10,000 civilians have been killed (United Nations, 2023). Ukraine’s GDP plunged by 30 percent in 2022, and the documented total damages to Ukraine’s economy have reached US$ 155 billion, as of January 2024 (KSE, 2024). Similarly, economic losses amount to around US$ 500 billion (as of December 2023). At the same time Ukraine’s reconstruction and recovery needs are estimated at about US$ 486 billion (World Bank, 2024). This immense number make up more than 2.5 times Ukraine’s 2023 GDP.

While there is a substantial and continuing international political and financial support for Ukraine’s defense, recovery, and reconstruction, this will not be enough (World Bank, 2023). Ukraine needs to mobilize its own resources and private financing, not just for its reconstruction but also for its long-term development. The Ukrainian government must leverage scarce public and donor resources and undertake necessary reforms to facilitate and crowd in private investments. One of the crucial reforms in this regard is the ongoing liberalization of the farmland market. The scale of its impact and capacity to generate private financing for agriculture and rural areas is frequently undervalued.

Ukraine’s Farmland Market and Reform

Almost 71 percent of Ukraine’s territory (or 42.7 million ha, including occupied territories) is farmland and 33 million ha is arable. This is far more than in the largest countries in the EU. Ukraine also has one-third of the world’s most fertile black soils. This resource has however been heavily underutilized for agricultural and overall economic development (KSE, 2021). Over the last two decades, Ukraine has turned into an increasingly important global supplier of staple foods (von Cramon-Taubadel and Nivievskyi, 2023), but this has largely happened without a full-fledged farmland market in Ukraine capable of facilitating even further agricultural productivity growth.

The farmland sales market was virtually non-existent for over three decades, instead rental transactions dominated. The farmland sales market began operating only in July 2021, and in a very limited format. Only individuals could purchase farmland plots and with a 100-ha cap per person. The minimum price was set at the normative monetary land value, and tenants had pre-emptive purchase rights while foreigners and legal entities were excluded; state and communal farmland remained under the 2001 sales ban. The farmland sales market opening was part of a large-scale land reform to support an efficient and transparent farmland market. This included a legislation package aimed at preventing land raiding, decentralizing land management, introducing electronic land auctions, establishing tools for land planning and use, creating a national infrastructure for geospatial data, establishing institutions for supporting small scale farmers, and empowering small scale farmers capacity to compete for land (KSE, 2021).

In general, there are two broad benefits of sales and lease transactions. First, the farmland market, via transactions, sorts out more efficient farms from less efficient ones, thus increasing the overall sector value added. Another important benefit, specifically linked to the farmland sales market, is that a functioning farmland sales market makes farmland a collateral which can generate productive investments in increased agricultural and non-agricultural productivity growth (Deininger and Nivievskyi, 2019).

Early Reform Outcomes

Almost two out of the first two and a half years of the reform phase unfolded amidst the profound shock from Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Following this, nearly 20 percent of Ukraine’s farmland has been occupied (Mkrtchian and Mueller, 2024), almost a third of the agricultural sector has been ruined – the total damages and losses to the agricultural sector amount to US$ 80 billion (Neyter at al., 2024). As a result, a very restrictive first-phase format of the market, on top of the war challenges, effectively limited the expected benefits of the market liberalization.

The war has put a sizable drag on the farm-land sales market development, effectively slashing the transacted volume almost by half (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Cumulative market transactions and the effect of the war.

Source: Nivievskyi and Neyter, 2024.

Overall, about 1.1 percent of total farmland area, or about 1.3 percent of Ukraine’s total controlled farmland (equivalent of 200,000 sales transactions or 444,300 ha) has been traded since the opening of the market. Regionally, the outcome is quite diverse (see Figure 2).

This is nonetheless an encouraging outcome as it is quite comparable to developed countries benchmarks where, on average, roughly 1 percent (and up to 5 percent) of the total agricultural land area is transacted annually (Nivievskyi et al., 2016). Another important outcome is that the transacted farmland has remained in agricultural production.

Farmland price development is also positive, especially for commercial farmland (see Figure 3). Since the commencement of the farmland sales market in Ukraine, the capitalization has increased by US$ 5.5 billion (KSE Agrocenter, 2024).

In fact, farmland market capitalization might be even greater. There are indications that the actual market price should be much higher, on average, than the officially registered one, as transacting parties may try and evade fees and taxes (Nivievskyi and Neyter, 2024).

Figure 2. Transacted area as share of total oblast (administrative region) area.

Source: The Center for Food and Land Use Research at Kyiv School of Economics (KSE Agrocenter), 2024.

Continued Farmland Market Liberalization and Associated Expectations

As of January 1, 2024, legal entities gained the right to acquire farmland that had, from 2001, been under sales ban. Also, in this second stage, the farmland accumulation cap per beneficiary increased to 10,000 hectares. Other restrictions remain, including that legal entities with a foreign beneficiary still cannot purchase farmland.

The first results of the second stage are premature, and firm conclusions cannot be drawn, yet the preliminary results are quite encouraging. The new market participants have already increased the volume of transactions and corresponding price by 13 percent, on average (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Average farmland prices, in thousands UAH.

Source: KSE Agrocenter (2024). Note: Demonstration and estimations are based on the State GeoCadaster Data.

Another encouraging result highlights that legal entities bring further transparency into the market. For half of the transactions involving individuals, the sales price did not exceed the minimum price by more than 1.5 percent, while in half of the farmland transactions with legal entities, the price exceeded the minimum one by more than 44 percent.

These early results provide insight into the market’s direction and the associated benefits. The expected economic benefits from liberalizing the farmland market for legal entities could amount to an annual increase of 1-2.7 percent of GDP over the next three years. The scale depends on many factors, including the availability of financing and financial support for small farmers (KSE Agrocenter, 2023).

Rural and agricultural financing is of particular interest as land is generally considered a high-quality collateral which could be utilized to attract loans and investments. This is particularly important during the current wartime period, as agricultural producers are facing significant collateral damage and severe financial difficulties for the third consecutive year. Currently, despite its potential, only a meager share of all farming loans is secured by farmland – far below global benchmarks.

Under current registered farmland prices, the total farmland market capitalization is equivalent to roughly US$ 35.5 billion. This could potentially generate an additional US$ 12.4 billion of loans (under the current low liquidity risk ratio of 0.35), already much greater than the current agricultural debt of about US$ 3.5 billion. Adding legal entities to the pool of farmland buyers (as of January 2024), is expected to increase farmland prices by an additional 40 percent. Thus, the farmland market will grow to almost US$ 50 billion, and the volume of land-secured financing could amount to US$ 17.5 billion. Further liberalization of the farmland market, such as a strengthening of its transparency, boosting the market liquidity, and accumulating necessary market statistics, may allow the National Bank of Ukraine to reconsider the liquidity risk ratio for farmland – potentially considering it as collateral similar to other types of real-estate (see the National Bank of Ukraine Resolution #351, June 30, 2016). A liquidity risk ratio at the level of developed countries (0.6-0.8) could further increase the volume of potential land-secured financing available to agriculture and rural areas/landowners to at least US$ 35 billion. This would, in turn, close the more than US$ 20 billion current financing gap for agricultural reconstruction, recovery and development. It would also contribute to Ukraine’s nearly US$ 500 billion reconstruction and recovery needs.

Further significant strides toward liberalizing Ukraine’s farmland sales market are anticipated as part of the country’s journey towards EU membership (European Commission, 2024), aligning with Chapter 4 ‘Free Movement of Capital’. Specifically, this pertains to allowing foreigners (EU citizens and legal entities) the right to purchase Ukrainian farmland (Nivievskyi and Neyter, 2024).

Conclusion

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has inflicted massive damage and losses to Ukraine, already amounting to more than 2.5 times Ukraine’s 2023 GDP. The recently estimated reconstruction and recovery needs measure at nearly US$ 500 billion. This is an unbearable burden for Ukraine alone. Despite substantial and continuing support from international partners and donors, Ukraine will need to heavily draw on its own resources and capacity to generate private financing, not just for the country’s reconstruction, but also for its long-term development. It is therefore essential, from the Ukrainian government’s perspective, to focus on necessary reforms and optimize policy decisions to leverage the scarce public and donor resources and facilitate and crowd in private investments. Continued farmland market liberalization is one such critical reform, providing hope to generate substantial private investment in the agricultural sector and rural areas.

The size of the farmland market is immense (with farmland accounting for more than 70 percent of Ukraine’s territory). The first two years following the opening of the farmland sales market demonstrate a substantial potential for private financing generation for agriculture and rural areas. The results from regular market monitoring and the early findings, as discussed above, suggest that further farmland market liberalization and increased transparency could generate about US$ 35 billion of financing for agricultural producers and rural areas/landowners. That could, in turn, close the current agricultural financing gap of more than US$ 20 billion for rebuilding and recovery, as well as partially close the nearly US$ 500 billion financing gap for Ukraine’s overall reconstruction and recovery. The expected economic benefits from liberalizing the farmland market for legal entities are estimated at 1-2.7 percent of GDP annually, over the next three years. A further liberalization of the farmland market, and a step towards EU membership, would include granting foreigners (EU citizens and legal entities) the right to buy Ukrainian farmland – expected to bring even further benefits.

References

- Deininger, K. and Nivyevskyi, O. (2019). Economic And Distributional Impact From Lifting The Farmland Sales Moratorium. Full Version, Vox Ukraine (20 November 2019)

- European Commission. (2024). Ukraine’s EU path.

- KSE Agrocenter. (2024). Land Market Review. January 2024.

- KSE Agrocenter. (2023). Land Market Review. 3Q 2023

- KSE. (2024). Damages to Ukraine’s Infrastructure. January 2024

- KSE. (2021). Strategy for the development of land relations in Ukraine, WHITE PAPER

- Mkrtchian, A. and Mueller, D. (2024). Satelitendaten Zeigen hohen Verlust an ukrainischen Anbauflaechen als Folge der russischen Invasion. Ukraine-Analysen #294

- Neyter, R. Zorya, S. and Muliar, O. (2024). Agricultural War Damages, Losses, and Needs Review, KSE Agrocenter

- Nivievskyi, O. and Neyter, R. (2024). Zwischenbilanz zum Krieg: Schäden und Verluste der ukrainischen Landwirtschaft, Ukraine-Analysen, Nr. 294, pp. 2-7

- Nivievskyi, O. and Neyter, R. (2024). Further Liberalization of the Farmland Sales Market in Ukraine. NL # 183

- Nivievskyi, O. Nizalov, D. and Kubakh, S. (2016). Restrictions on farmland sales markets: a survey of international experience and lessons for Ukraine, Kyiv School of Economics

- The New York Times. (2023). Troop Deaths and Injuries in Ukraine War Near 500,000, U.S. Officials Say

- United Nations. (2023). Civilian Deaths in Ukraine War Top 10,000 UN Says

- UNHCR. (2024). Ukraine Situation Flash Update #63

- von Cramon-Taubadel, S. and Nivievskyi, O. (2023). Rebuilding Ukraine – the Agricultural Perspective, EconPol Forum 2, Volume 24, pp. 36-40

- World Bank. (2023). Private Sector Opportunities for a Green and Resilient Reconstruction in Ukraine. Synthesis Report. October 2023

- World Bank. (2024). Ukraine. Third Rapid Damage and Needs Assessment (RDNA3). February 2022 – December 2023

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in policy briefs and other publications are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect those of the FREE Network and its research institutes.

How to Sustain Support for Ukraine and Overcome Financial and Political Challenges | SITE Development Day 2022

This policy brief explores how Europe and global partners can sustain support for Ukraine’s reconstruction following Russia’s invasion. Drawing from expert discussions at SITE Development Day 2022, it highlights strategies for rebuilding Ukraine’s economy, democracy, and energy infrastructure.

Introduction

The Russian war on Ukraine has turmoiled Europe into its first war in decades and while the effects of the war are harshly felt in Ukraine with lives lost and damages amounting, Europe and the rest of the world are also being severely affected. This policy brief shortly summarizes the presentations and discussions at the SITE Development Day Conference, held on December 6, 2022. The main focus of the conference was how to maintain and organize support for Ukraine in the short and long run, with the current situation in Belarus and the region and the ongoing energy crisis in Europe, also being addressed.

War in Ukraine, Oppression in Belarus

Starting off the conference, Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, Leader of the Belarusian Democratic Forces, delivered a powerful speech on the necessity of understanding the role of Belarus in the ongoing war in Ukraine. Tsikhanouskaya argued that Putin’s war on Ukraine was partly a result of the failed Belarusian revolution of 2020. The following oppression, torture, and mass arrestations of Belarusians is a consequence of Lukashenka’s and Putin’s fear of a free Belarus, a Belarus that is no longer in the hands of Putin – who sees not only Belarus but also Ukraine as colonies in his Russian empire. Amidst the fight for Ukraine, we must also fight for a free Belarus, Tsikhanouskaya added. Not only Belarusians fighting alongside Ukrainians against Russia in Ukraine, but also other parts of the Belarusian opposition need support from the free and democratic world and the EU. The massive crackdowns on opponents of the Belarusian regime today and the war on Ukraine are not only acts of violence, but they are also acts against democracy and freedom. The world must therefore continue to give support to those fighting in both Belarus and Ukraine. Ukraine will never be free unless Belarus is free, Tsikhanouskaya concluded.

Johan Forssell, Minister of Foreign Trade and International Development Cooperation continued Tsikhanouskaya’s words on how the Russian attack must be seen and treated as a war on democracy and the free world. Belarus, Moldova and especially Ukraine will receive further support from Sweden, Forssell continued, adding that the Swedish support to Ukraine has more than doubled since the invasion in February 2022. Support must however not be given only in economic terms and consequently Sweden fully supports Ukraine on its path to EU-membership, which will be especially emphasized during Sweden’s upcoming EU-presidency. Support for the rule of law, democracy and freedom will continue to be essential and, in the forthcoming reconstruction of Ukraine, these aspects – alongside long term sustainable and green solutions – must be integrated, Forssell continued. Forssell also mentioned the importance of reducing the global spillover effects from the war. In particular, Forssell mentioned how the war has struck countries on the African continent, already hit with drought, especially hard with increased food prices and increased inflation, displaying the vital role Ukrainian grain exports play.

Andrij Plachotnjuk, Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of Ukraine to the Kingdom of Sweden, further talked about the need for rebuilding a better Ukraine, emphasizing the importance of involvement from Kiyv School of Economics (KSE) and other intellectuals and businesses in this process. Plachotnjuk also pinpointed what many others would come to repeat during the day; that resources, time and efforts devoted to supporting Ukraine must be maintained and persevered in the longer perspective.

Economic Impacts From the War and How the EU and Sweden Can Provide Support

During the first half of the conference, the Ukrainian economy and how it can be supported by the European Union was also discussed. On link from Kiyv, Tymofiy Mylovanov, President of the Kyiv School of Economics, shared the experiences of the University during wartime and presented the work KSE has undertaken so far – and how this contributes to an understanding of the damages and associated costs. Since the invasion, KSE has supported the government in three key areas; 1) Monitoring the Russian economy, 2) Analyzing what sanctions are relevant and effective, and 3) Estimating the cost of damages from the war. For the latter, KSE is collaborating with the World Bank using established methods of damage assessment including crowd sourced information on damages complemented with images taken by satellites and drones. According to Mylovanov, the damage assessment is crucial in order to counter Russia’s claims of a small conflict and to remind the international community of the high price Ukraine is paying to hold off Russia.

The economic impact from the war was further accentuated during the presentation by Yulia Markuts, Head of the Centre of Public Finance and Governance Analysis at the Kyiv School of Economics. Markuts explained how the Ukrainian national budget as of today is a “wartime budget”. Since February 2022, the budget has been reoriented with defense and security spending having increased 9 times compared to 2021, whereas only the most pressing social expenditures have been implemented. This in a situation where the Ukrainian GDP has simultaneously decreased by 30 percent. Although there has been a substantial inflow of foreign aid, in the form of grants and loans, the Ukrainian budget deficit for 2023 is estimated to 21 percent. Part of the uncertainty surrounding the Ukrainian budget stems from the fact that the inflow from the donor community is irregular, prompting the government to cover budget deficits through the National Bank which fuels inflation and undermines the exchange rate. Apart from the large budget posts concerning military spending, major infrastructural damages are putting further pressure on the Ukrainian budget in the year to come, Markuts continued. As of November 2022, the damages caused by Russia to infrastructure in Ukraine amounted to 135,9 billion US Dollars, with the largest damages having occurred in the Kiyv and Donetsk regions, as depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Ukrainian regions most affected by war damages, as of November 2022.

Source: Kiyv School of Economics

The infrastructural damages constitute a large part of the estimated needed recovery support for Ukraine, together with losses to the state and businesses amounting to over one trillion US Dollars. However, such estimates do not cover the suffering the Ukrainian people have encountered from the war.

The large need for steady support was discussed by Fredrik Löjdquist, Centre Director of the Stockholm Centre for Eastern European Studies (SCEEUS), who argued the money needs to be seen as an investment rather than a cost, and that we at all times need to keep in mind what the consequences would be if the support for Ukraine were to fizzle out. Löjdquist, together with Cecilia Thorfinn, Team leader of the Communications Unit at the Representation of the European Commission in Sweden, also emphasized how the reconstruction should be tailored to fit the standards within the European Union, given Ukraine’s candidacy status. Thorfinn further stressed that the reconstruction must be a collective effort from the international community, although led by Ukraine. The EU is today to a large extent providing their financial support to Ukraine through the European Investment Bank (EIB). Jean-Erik de Zagon, Head of the Representation to Ukraine at the EIB, briefly presented their efforts thus far in Ukraine, efforts that have mainly been aimed at rebuilding key infrastructure. Since the war, the EIB has deployed an emergency package of 668 million Euro and 1,59 billion for the infrastructure financing gap. While all member states need to come together to ensure continued support for Ukraine, the EIB is ready to continue playing a key role in the rebuilding of Ukraine and to provide technical assistance in the upcoming reconstruction, de Zagon said. This can be especially fruitful as the EIB already has ample knowledge on how to carry out projects in Ukraine.

During a panel discussion on how Swedish support has, can and should continuously be deployed, Jan Ruth, Deputy Head of the Unit for Europe and Latin America at Sida, explained Sida’s engagement in Ukraine and the agency’s ambition to implement a solid waste management project. The project, in line with the need for a green and environmentally friendly rebuild, is today especially urgent given the massive destructions to Ukrainian buildings which has generated large amounts of construction waste. Karin Kronhöffer, Director of Strategy and Communication at Swedfund, also accentuated the need for sustainability in the rebuild. Swedfund invests within the three sectors of energy and climate, financial inclusion, and sustainable enterprises, and hash previously invested within the energy sector in Ukraine. Swedfund is also currently engaged in a pre-feasibility study in Ukraine which would allow for a national emergency response mechanism. Representing the business side, Andreas Flodström, CEO and founder of Beetroot, shared some experiences from founding and operating a tech company in Ukraine for the last 10 years. According to Flodström there will, apart from a huge need in investments in infrastructure, also be a large need for technical skills in the rebuild. Keeping this in mind, bootcamp style educations are a necessity as they provide Ukrainians with essential skills to rebuild their country.

A recurring theme in both panel discussions was how the reconstruction requires both public and private foreign investments. Early on, as the war continues, public investments will play the dominant part, but when the situation becomes more stable, initiatives to encourage private investments will be important. The potential of using public resources to facilitate private investments through credit guarantees and other risk mitigation strategies was brought up both at the European and the Swedish level, something which has also been emphasized by the new Swedish government.

Impacts From the War Outside of Ukraine – Energy Crisis and Other Consequences in the Region

The conference also covered the effects of the war outside of Ukraine, initially keying in on the consequences from the war on energy supply and prices in Europe. Chloé Le Coq, Professor of Economics, University Paris-Pantheon-Assas (CRED) & SITE, gave a presentation of the current situation and the short- and long-term implications. Le Coq explained that while the energy market is in fact functioning – displaying price increases in times of scarcity – the high prices might lead to some consumers being unable to pay while some energy producers are making unprecedented profits. The EU has successfully undertaken measures such as filling its gas storage to about 95 percent (goal of 80 percent), reducing electricity usage in its member countries, and by capping market revenues and introducing a windfall tax. While the EU is thus appearing to fare well in the short run, the reality is that EU has increased its coal dependency and paid eight times more in 2022 to fill its gas storage (primarily due to the imports of more costly Liquified Natural Gas, LNG). In the long run, these trends are concerning, given the negative environmental externalities from coal usage and the market uncertainty when it comes to the accessibility and pricing of LNG. Uncertainties and new regulations also hinder investments signals into new low-carbon technologies, Le Coq concluded. Bringing an industrial perspective to the topic, Pär Hermerèn, Senior advisor at Jernkontoret, highlighted how the energy crisis is amplified by the increased electricity demand due to the green transition. Given the double or triple upcoming demand for electricity, Hermerèn, referred back to the investment signals, saying Sweden might run the risk of losing market shares or even seeing investment opportunities leave Sweden. This aspect was also highlighted by Lars Andersson, Senior advisor at Swedenergy, who, like Hermerèn, also saw the Swedish government’s shift towards nuclear energy solutions. Andersson stated the short-term solution, from a Swedish perspective, to be investments into wind power, urging policy makers to be clear on their intentions in the wind power market.

Other major impacts from the war relate to migration, a deteriorating Belarusian economy and security concerns in Georgia. Regarding the latter, Yaroslava Babych, Lead economist at ISET Policy Institute, Georgia, shared the major developments in Georgia post the invasion. While the Georgian economic growth is very strong at 12 percent, it is mainly driven by the influx of Russian money following the migration of about 80 000 Russians to Georgia. This has led to a surge in living costs and an appreciation of the local currency (the Lari) of 12,6 percent which may negatively affect Georgian exports. Additionally, it may trigger tensions given the recent history between the countries and the generally negative attitudes towards Russians in Georgia. Michal Myck, Director at CenEa, Poland, also presented migration as a key challenge. While the in- and outflow of Ukrainian refugees to Poland is today balanced, the majority of those seeking refuge in Poland are women and children and typically not included in the workforce. To ensure successful integration and to avoid massive human capital losses for Ukraine, Myck argued education is key, pointing to the lower school enrollment rates among refugee children living closer to the Ukrainian border. Apart from the challenges posed by the large influx of Ukrainian in the last year, the Polish economy is also hit by high energy prices, fuel shortages and increasing inflation. Lev Lvovskiy, Research fellow at BEROC, Belarus, painted a similar but grimmer picture of the current economic situation in Belarus. Following the invasion, all trade with Ukraine has been cut off, while trade with Russia has increased. Belarus is facing sanctions not only following the war, but also from 2020, and the country is in recession with GDP levels dropping every month since the invasion. Given the political and economic situation, the IT sector has shrunk, companies oriented towards the EU has left the country and real salaries have decreased by 5 percent. At the same time, the policy response is to introduce price controls and press banknotes.

Consequences of War: An Academic Perspective

The later part of the afternoon was kicked off by a brief overview of the FREE Network’s research initiatives on the links between war and certain development indicators. Pamela Campa, Associate Professor at SITE, presented current knowledge on the connection between war and gender, with a focus on gender-based violence. Sexual violence is highly prevalent in armed conflict and has been reported from both sides in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions since 2014 and during the ongoing war, with nearly only Russian soldiers as perpetrators. Apart from the direct threats of sexual violence during ongoing conflict and fleeing women and children risking falling victims to trafficking, intimate partner violence (IPV) has been found to increase post conflict, following increased levels of trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). While Ukrainian policy reforms have so far strengthened the response to domestic violence there is still a need for more effective criminalization of domestic violence, as the current limit for prosecution is 6 months from the date crime is committed. An effective transitional justice system and expertise on how to support victims of sexual violence in conflict, alongside economic safety measures undertaken to support women and children fleeing, are key policy concepts Campa argued. Coming back to the broader topic of gender and war, Campa highlighted the need for involvement of women in peace talks and negotiations, something research suggests matter for both equality, representativeness, and efficiency.

Providing insights into the relationship between the environment and war, Julius Andersson, Assistant Professor at SITE, initially summarized how climate change may cause conflict along four channels: political instability and crime rates increasing as a consequence of higher temperatures, scarcity of natural resources and environmental migration. Conflict might however also cause environmental degradation in the form of loss of biodiversity, pollution and making land uninhabitable. As for the negative impact from the war in Ukraine, Andersson highlighted how fires from the war has caused deforestation affecting the ecosystems, that rivers in conflict struck areas in Ukraine and the Sea of Azov are being polluted from wrecked industries (including the Azovstal steelworks) and lastly that there is a real threat of radiation given the four major nuclear plants in Ukraine being targeted by Russian forces. Coming back to a topic mentioned earlier during the day, Andersson also emphasized potential conflict spillovers into other parts of the world due to the war’s impact on food and fertilizer prices.

Concluding the session, Jonathan Lehne, Assistant Professor at SITE, reviewed how war and democracy is tied to one another, highlighting that while studies have found that democracies per se are not necessarily less conflict prone, it is still the case that democratic countries almost never fight each other. As for the microlevel takeaways from previous research, it appears as if individuals and communities having experienced violence and casualties actually reap a democratic dividend in some respects, such as greater voting participation. On the other hand, while areas with a large refugee influx also experience an increased voter turnout, voting for right-wing parties also increase with politicians exploiting this in their communication.

Book Launch – Reconstruction of Ukraine: Principles and Policies

The Development Day was also guested by Ilona Sologoub, Scientific Editor at VoxUkraine, Tatyana Deryugina, Associate Professor of Finance at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and Torbjörn Becker, Director of SITE, who presented their newly released book “Reconstruction of Ukraine: Principles and policies”. Sologoub started off by giving an overview of the mainly economic topics covered in the book and pointing out that the main purpose of the book is to inform policy makers about the present situation and to suggest needed reforms and investments. Becker outlined the four key principles recommended to stem corruption during reconstruction; 1) Remove opportunities for corruption and rent extraction, 2) Focus on transparency and monitoring of the whole reconstruction effort, 3) Make information and education an integral part of the anti-corruption effort, and 4) Set up legal institutions that are trusted when corruption does occur. Deryugina focused on the energy sector and related back to what had previously been discussed throughout the day, the need to “build-back-better”. Deryugina mentioned that Ukraine, previously heavily reliant on coal and gas imports from Russia, now have the opportunity to steer away from low energy efficiency and bottleneck issues, towards becoming a European natural gas hub. The book is available for free here. There will also be a book launch on the 11th of January 2023 at Handelshögskolan.

Concluding Remarks

Via link from Kyiv, Nataliia Shapoval, Head of KSE Institute and Vice President for Policy Research at Kyiv School of Economics closed the conference by emphasizing the urgency of continued education of Ukrainians in Ukraine and elsewhere to avoid loss of Ukrainian human capital. Shapoval also stressed how universities can act as thinktanks, support policy makers in Ukraine and Europe to come up with effective sanctions against Russia and provide a deeper understanding of the current situation – a situation which will linger and in which Ukraine needs continued full support.

This year’s SITE Development Day conference gave an opportunity to discuss the need for continued support for Ukraine and the implications from the war in a global, European, and Swedish perspective. Representatives from the political, public, private and academic sectors contributed with their insights into the challenges and possibilities at hand, providing greater understanding of how the support can be sustained, with the goal of a soon end to the war and a successful rebuild of Ukraine.

List of Participants in Order of Appearance

- Anders Olofsgård, Deputy Director at SITE

- Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, Leader of the Belarusian Democratic Forces

- Johan Forssell, Minister of Foreign Trade and International Development Cooperation

- Andrij Plachotnjuk, Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of Ukraine to the Kingdom of Sweden

- Tymofiy Mylovanov, President of the Kyiv School of Economics (on link from Kyiv)

- Yuliya Markuts, Head of the Centre of Public Finance and Governance Analysis, Kyiv School of Economics

- Jean-Erik de Zagon, Head of the Representation to Ukraine at the European Investment Bank

- Cecilia Thorfinn, Team leader of the Communications Unit at the Representation of the European Commission in Sweden

- Fredrik Löjdquist, Centre Director of the Stockholm Centre for Eastern European Studies (SCEEUS)

- Jan Ruth, Deputy Head of the Unit for Europe and Latin America at Sida

- Karin Kronhöffer, Director of Strategy and Communication at Swedfund

- Andreas Flodström, CEO and founder of Beetroot

- Chloé Le Coq, Professor of Economics, University Paris-Pantheon-Assas (CRED) & SITE

- Lars Andersson, Senior advisor at Swedenergy

- Pär Hermerèn, Senior advisor at Jernkontoret

- Ilona Sologoub, VoxUkraine scientific editor (on link)

- Tatyana Deryugina, Associate Professor of Finance at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (on link)

- Torbjörn Becker, Director at SITE

- Michal Myck, Director at CenEa, Poland

- Yaroslava Babych, Lead economist at ISET Policy Institute, Georgia

- Lev Lvovskiy, Research fellow at BEROC, Belarus

- Pamela Campa, Associate Professor at SITE

- Julius Andersson, Assistant Professor at SITE

- Jonathan Lehne, Assistant Professor at SITE

- Nataliia Shapoval, Head of KSE Institute and Vice President for Policy Research at Kyiv School of Economics (on link)

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in policy briefs and other publications are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect those of the FREE Network and its research institutes.

Further Reading on Support for Ukraine’s Reconstruction and Post-Conflict Recovery

Additional analyses related to Ukraine’s reconstruction, European security, and post-conflict policy are available in the following reports and policy briefs:

- How to Rebuild Ukraine – Report by FREE Network authors, “A Synthesis and Critical Review of Policy Proposals.”

- How should Europe rethink its security in the face of the russian threat? – Report by the KSE Institute, “Rethinking European Security in the Face of the Russian Threat.”

- Should frozen russian state assets be seized to support Ukraine’s reconstruction? – Policy brief by Anders Olofsgård, Associate Professor at SITE, “The Case for Seizing Russian State Assets.”

Related publications addressing European policy toward Eastern Europe, post-conflict recovery economics, and the energy crisis in Europe further contribute to understanding the broader geopolitical and economic dimensions of the war’s impact. For comprehensive research and expert insights on Ukraine’s reconstruction, European aid, and post-war recovery, explore the FREE Network policy briefs under the Ukraine and Russo-Ukrainian War categories.

IMF’s New SDR Allocation—Why Belarus Is “Getting Money From the Fund”

Why is the IMF sending $1bn to Belarus as the country is falling deeper into repression and authoritarianism? The short answer is that Belarus, together with 189 other countries, is a member of the IMF and the institution has decided to make a $650bn allocation of SDRs to its members in proportion to their quotas in the IMF. Belarus has a quota of 0.14 and will thus receive an injection of around $1bn to its reserves. In other words, this is not a decision to support the Belarus government as such but a general decision by the IMF members to support a global recovery after the Covid-19 pandemic. That said, it still means that the leaders of Belarus are given an asset worth $1bn that can be used without conditions, but the underlying reason to support the recovery in low- and middle-income countries still makes this palatable.

Introduction

On August 2, 2021, the board of the IMF approved the largest-ever SDR allocation to its 190 member countries. Belarus is one of the members that, by this decision, will get a boost of reserve assets of almost $1 billion. This has raised the question in some circles of “why is the IMF giving money to Belarus”. This brief provides a short background on IMF SDR allocations; how this may be used by the autocratic regime of Belarus; and why the general SDR allocation still makes sense.

SDR Allocations

For most people, an IMF “SDR allocation” is just another mysterious acronym that means very little. Therefore, a short introduction to the concept is warranted. SDR is short for Special Drawing Rights and is the IMF’s own reserve asset and unit of account, with a value that was first linked to gold but is now based on a basket of other currencies (IMF 2021). More specifically, the value of the SDR is based on a basket that consists of the U.S. dollar, euro, yen, pound sterling, and Chinese renminbi (since 2016). Table 1 shows the amounts of each currency and the value of the SDR based on exchange rates for August 26, 2021. In short, on that date, 1 SDR was worth approximately 1.42 U.S. dollars. Since the cross-exchange rates in the basket vary over time, so does the value of the SDR (see Figure 1).

Table 1. The SDR basket

Source: IMF (https://www.imf.org/external/np/fin/data/rms_sdrv.aspx)

Figure 1. SDR valuation

Source: IMF’s IFS database

The next issue is how SDRs are allocated among the IMF members. This is determined by the IMF’s Articles of Agreement and is done to provide reserve assets to its member countries. A new SDR allocation requires an 85 percent majority in the board to pass, and SDRs are then allocated to members based on their quotas. IMF quotas, in turn, are basically the stake the different member countries have in the Fund and are roughly based on the size of the economy of the country relative to other members. Since several countries joined the IMF after the general SDR allocations in 1981, a special allocation was done in 2009 to allow new member countries to join the SDR Department on more equal terms. There was also a large general allocation in 2009 during the global financial crisis and in 2021 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 2). The latter one is by far the largest and given the exchange rate in Table 1, the SDR456.5 billion is equivalent to around $650 billion.

Figure 2. SDR allocations

Source: IMF, 2021 (https://www.imf.org/en/About/Factsheets/Sheets/2016/08/01/14/51/Special-Drawing-Right-SDR)

The final issue to address in this section is why the SDR allocations matter at all. The answer is that SDRs can be exchanged for other currencies that, in turn, can be used to buy goods and services in international markets, including vaccines, other medical equipment, services, or food. When countries use the SDRs in this way, there is a cost in terms of the interest rate countries pay on SDRs. However, this interest rate is very low compared to other types of borrowing, so it is a cheap way of getting more foreign currency to spend (see Figure 3). In other words, for countries lacking access to foreign exchange at reasonable costs, the SDR allocation is a very welcome addition to their spending power.

Figure 3. Interest rate on SDR

Source: IMF’s Finance Department

Belarus and the IMF

Belarus became a member of the IMF in July 1992, shortly after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Its quota in the IMF is SDR 681.5 million (or a share of 0.14 percent of total).

Belarus has had two IMF programs so far, the first in the early 1990s and the second in the wake of the global financial crisis in 2009. In the latter program, the IMF board approved a $2.5 billion loan “in support of the country’s efforts to adjust to external shocks” on January 12, 2009 (IMF, 2009a). The loan was then increased to a total of $3.5 billion in June 2009 (IMF, 2009b).

Despite the need for reforms and external funding, Belarus could not reach an agreement with the IMF on continued funding and instead repaid the loans to the Fund between 2012 and 2015. At the heart of this was the fact that for a country to get financial support in a regular Fund program, conditions will apply and will not always be stated explicitly, including on how to deal with human rights issues that are outside the Fund’s mandate. Therefore, the previous money from the Fund to Belarus was fundamentally different from the general SDR allocation described here, which is money without strings attached.

As the Covid-19 pandemic hit economies across the globe, Belarus approached the Fund in March 2020 to seek financial assistance. According to various reports, Belarus could not reach an agreement with the IMF due to conditions on how the pandemic was to be handled (IMF, 2020).

The new SDR allocation is however NOT subject to any conditionality but distributed to IMF members in proportion to their quotas. For Belarus, this means a new SDR allocation of 0.14 percent of the total SDR 456.5 billion, equivalent to around $900 million. As explained above, the SDR allocation can be exchanged for dollars, euros, or other currencies that can then be used to buy whatever the regime in Belarus likes. It could be vaccines, food, and medical equipment, but it could also be guns, ammunition, or tear gas to the security forces. In other words, this is money that can be spent in any way the government decides and the only price for this is a very small interest charge (see Figure 3) that comes with not keeping the SDRs as a reserve asset.

Concluding Remarks

The IMF is a member institution with 190 countries that is governed by its Articles of Agreement. This dictates that a new general SDR allocation should be distributed to its members according to their quotas. New SDR allocations are rare but have been used before to handle global economic crises. The current SDR allocation is designed to help low- and middle-income countries to deal with the economic side of the Covid-19 by making more foreign exchange available at a low cost. Helping countries with limited reserves to deal with the crisis and ensure that they can secure imports of vital goods and services makes perfect sense. The fact that this general support in certain instances will go to regimes like the one in Belarus that we currently think do not warrant the support of the global community is unfortunate. In a perfect world, the IMF would be able to impose conditions on human rights and democracy for any type of financial support, but this is not the world we live in. Therefore, the conclusion is not to stop helping a global recovery but to do more to support the alternatives to autocratic regimes across the world with other instruments.

References

- IMF, 2020, https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2020/09/10/tr091020-transcript-of-imf-press-briefing

- IMF 2009a, https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2015/09/14/01/49/pr0905

- IMF, 2009b , https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2015/09/14/01/49/pr09241 ).

- IMF, 2021, https://www.imf.org/en/About/Factsheets/Sheets/2016/08/01/14/51/Special-Drawing-Right-SDR

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in policy briefs and other publications are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect those of the FREE Network and its research institutes.

Socio-Economic Policy in Poland: A Year of Major Changes in Benefits, Taxes, and Pensions

2016 was the first full calendar year of the new Polish government elected to power in October 2015. The year marked a number of major changes legislated in the area of socio-economic policy some of which have already been implemented and others that will take effect in 2017. In this policy brief, we analyse the distributional consequences of changes in the direct tax and benefit system, and discuss the long-term implications of these policies in combination with the policy to reduce the statutory retirement age.

The Law and Justice party (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, PiS) won an absolute majority of seats in both houses of the Polish Parliament in the parliamentary elections of October 2015. Earlier that year, Andrzej Duda of PiS was elected President of the Polish Republic. In both cases, the electoral victories came on the wave of pledges of significant financial support to families with children and to low-income households, especially pensioners. The new president pledged to cut back the pension age to the levels prior to the 2012 reform, which introduced a gradual increase from 60 and 65 to 67 for both women and men, and to nearly triple the income tax allowance. Following Duda’s victory in May 2015, PiS reiterated these pledges in the parliamentary election campaign and added the promise to increase the total level of financial support for families with children by over 140% through a nearly universal benefit called “Family 500+” and to hike the minimum wage by over 8%.

Despite a rather tight budget situation, the government went ahead with the “Family 500+” and successfully rolled it out in April 2016 (Myck et al., 2016a). The new instrument directs support of 500 PLN per child per month (110 EUR) to all second and subsequent children in the family in the age group between 0 and 17. Benefits for the first child in the family in this age group are granted conditional on overcoming an income threshold of 800 PLN (180 EUR) per person per month. Since April 2016, over 2.7 million families have received the benefit and 60% of them received the means tested support (if they have more than one child this is paid out in combination with the universal benefit).

The second key electoral pledge – to increase the tax allowance from 700 to 1,850 EUR at an estimated cost of 4.8 billion EUR – has so far been postponed (CenEA, 2015a). Increases in the allowance became a major policy issue in October 2015 when the Constitutional Tribunal ruled that maintaining its level below minimum subsistence, as it was at the time, was unconstitutional. To satisfy the Tribunal’s ruling, the allowance would have to increase to ca. 1,500 EUR at a cost of nearly 15 billion PLN (3.4 billion EUR, and about 0.8% of GDP, CenEA 2015b). Instead of a simple increase in the allowance, the government decided to implement a digressive tax allowance for 2017. This raised the value to the required minimum subsistence level for the lowest income tax payers, but since it is rapidly withdrawn as taxable income rises, the allowance will be unchanged to a large majority of taxpayers and will cost the public purse only 0.2 billion EUR (CenEA, 2016). This policy will be more than paid for by the fiscal drag given the decision to freeze all other parameters of the tax system, which will cost the taxpayers 0.5 billion EUR (Myck et al., 2016b).

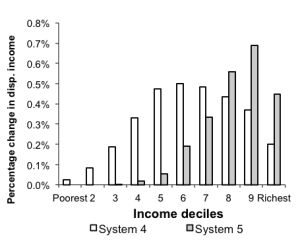

The policies that directly affect household budgets will in total amount to about 5.5 billion EUR in 2017 (1.3% of GDP and 6.2% of the planned central budget expenditures) and will include also an increase in the minimum pension to benefit about 1.5 million pensioners. The cost of the “Family 500+” reform makes up the large majority of this value (5.4 billion EUR). Households from the lower income decile groups will benefit the most from this reform package, with their monthly disposable income increasing on average by 15.1% (ca. 60 EUR). High-income households from the top income decile will see their income grow on average by only 0.5% (see Figure 1). Overall, nearly all of the gains will go to families with children, with single parents gaining on average about 95 EUR and married couples with children about 84 EUR per month. Other types of families will, on average, see negligible changes in their household disposable incomes (see Figure 2). Thus, the implemented package clearly has a very progressive nature and redistributes significant resources to families with children.

Figure 1. Distributional consequences of changes in direct tax and benefit measures implemented between 2016-2017

Source: calculations using CenEA’s microsimulation model SIMPL based on PHBS 2014 data.

Source: calculations using CenEA’s microsimulation model SIMPL based on PHBS 2014 data.

The pension age and public finances in the years to come

The most recent major reform, legislated at the end of 2016 and which will come into effect in October 2017, represents an implementation of yet another costly electoral pledge. This policy has overturned gradual increases in the statutory retirement age, initiated by the previous government in 2012. Despite the very rapid ageing of the Polish population, the new government decided to return to the pre-2012 retirement ages of 60 and 65 for women and men, respectively. This comes at a time when, according to EUROSTAT (Eurostat, 2014), the old-age dependency ratio in Poland, i.e. the proportion of the 65+ population to the working-age population, will grow from the current 24% to 27% in 2020 and to 40% in 2040. With the defined contribution pension system, the shorter working lives resulting from this change will be reflected in significantly reduced benefits (Figure 2). For example, pension benefits of men retiring in 2020 will on average be 13.5% lower than the pre-reform value. For women that retire in 2040, the pension benefits will on average fall by 15.2%, which corresponds to a 43% lower benefit than the pre-reform value, and with consequences of the reform becoming more severe over time. The reform will also be very costly to the government budget. In 2017, it is expected to cost 1.3 billion EUR and its full effect will kick in after 2021, when the cost of the reform will exceed 3.9 billion EUR per year (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Reducing the statutory retirement age and its implications on pension benefits and public finances

Source: Based on data from Council of Ministers (2016).

Source: Based on data from Council of Ministers (2016).

Conclusion

Since coming to power in October 2015, the PiS government has implemented a majority of its costly electoral pledges. Direct changes in taxes and benefits will cost 5.5 billion EUR in 2017 and benefit primarily those in the lower end of the income distribution and in particular families with children. The reduced statutory retirement age will add an extra 1.3 billion EUR in 2017 and as much as 3.9 billion EUR four years later. The very generous “Family 500+” programme has significantly reduced child poverty and may have important positive long-term effects in terms of health and education for today’s beneficiaries. However, its fertility implications are still uncertain and the programme is expected to reduce the employment rate among mothers. While the government maintains that its financing is secured, it is becoming clear that maintaining the policy will not be possible without higher taxes.

The government came to power claiming that the implementation of this programme will be based on reducing tax fraud and that only a small fraction will be financed from tax increases. While it seemed likely at the time when these declarations were made, the expected major shift in the reduction of tax fraud has yet not materialised. The government have withdrawn from the pledge of reducing the VAT and from assisting those with mortgages denominated in Swiss Francs, while its income tax allowance reform was nearly thirty times less expensive compared to that announced in its electoral programme.

With a very tight budget for 2017 based on relatively optimistic assumptions, the key factors determining further realisations of the generous programme will be the rate of economic growth and related dynamics on the labour market. Developments of the labour market will also be essential for the longer-term economic success of the implemented reform package. This relates both to the future level of participation of women and to the success of extend working lives of people who will soon reach the new reduced retirement age.

References

- CenEA (2015a) Konsekwencje prezydenckiej propozycji podwyższenia kwoty wolnej od podatku (Consequences of the presidential proposal to raise the incoem tax allowance), CenEA press release, 3 December 2015.

- CenEA (2015b) Co z kwotą wolną od podatku po wyroku Trybunału Konstytucyjnego? (what will happen to the income tax allowance after the decision of the Constitutional Tribunal?), CenEA press release, 13 November 2015.

- CenEA (2016) Zmiany w kwocie wolnej od podatku za 800 mln rocznie (Changes in the income tax allowance at the cost of 800m per year), CenEA press release, 29 November 2016.

- EUROSTAT (2014) Eurostat – Population projections EUROPOP2013, access 21 December 2016.

- Myck, M., Kundera, M., Najsztub, M., Oczkowska, M. (2016a) 25 miliardów złotych dla rodzin z dziećmi: projekt Rodzina 500+ i możliwości modyfikacji systemu wsparcia. (25bn for families with children: plans for the Family 500+ reform and other options to modify the system of support.), CenEA Commentaries, 18 January 2016.

- Myck, M., Kundera, M., Najsztub, M., Oczkowska, M., 2016b, Zamrożony PIT i utrzymane wyższe stawki VAT – jak brak zmian w podatkach wpłynie na budżety gospodarstw domowych? (Frozen PIT and higher VAT – how lack of changes in taxees will affect househod budgets?), CenEA Commentaries, 05 October 2016.

- Council of Ministers (2016) Position of the Council of Ministers on the presidential bill proposal, Warsaw, 25 July 2016.

Financial Support for Families with Children and Its Trade-Offs: Balancing Redistribution and Parental Work Incentives

Authors: Michal Myck, Anna Kurowska and Michal Kundera, CenEA.

Reforms of tax-benefit system of financial support for families with children have a broad range of consequences. In particular, they often imply trade-offs between effects on income redistribution and work incentives for first and second earners in the family. Understanding the complexity of the consequences involved in reforming family policy is crucial if the aim is to “kill two birds with one stone” namely to reduce poverty and improve incentives to work. In this brief, we illustrate these complex trade-offs by analyzing several scenarios of reforming financial support for families with children in Poland. We show that it is possible to create incentives for second earners in the family to join the labor force without destroying the work incentives of the first earners. Moreover, the same reform would allocate resources to families with lower incomes, which could result in a direct reduction of child poverty.

Financial support for families with children is an important and integral part of the broad family policy package, the goals of which fall into two basic categories of reducing child poverty and increasing labour market activity of parents (Whiteford and Adema, 2007; Björklund, 2006; Immervoll, et al., 2001). However, the particular policy aimed at one of these objectives may be detrimental to the achievement of other goals. For example, family/child benefits may directly increase family income and thus reduce child poverty. These same benefits could have a negative effect on parental incentives to work, particularly for so-called second earners, usually mothers (see e.g. Kornstad and Thoresen, 2007). However, employment of both parents often turns out to be crucial for a long-term poverty reduction (Whiteford and Adema, 2007).