Tag: EU accession

Moldova’s EU Integration and the Special Case of Transnistria

In the shadow of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, another East European country is actively working to secure its European future. After three years of negotiating cooperation agreements with the European Commission, Moldova finally obtained its EU candidate status and is now on track to join the EU as a member state. However, among many remaining obstacles on the path to full membership, one stands out as especially problematic: the region of Transnistria. The region, officially Pridnestrovian Moldovan Republic, is an internationally unrecognized country and is rather seen as a region with which Russia has “special relations”, including a military presence in the region since 1992. This policy brief provides an overview of the current state of the Transnistrian economy and its relationships with Moldova, the EU, and Russia, arguing that Transnistria’s economy is de facto already integrated into the Moldovan and EU economies. It also points to the key challenges to resolve for a successful integration of Moldova into the EU.

Moldova’s EU Integration: The Moldovan Economy on its Path to EU Accession

On December 14th, 2023, the European Council decided to open accession negotiations with Moldova, recognizing Moldova’s substantial progress when it comes to anti-corruption and de-oligarchisation reforms. The first intergovernmental conference was held on the 25th of June 2024, officially launching accession negotiations (European Council, 2024). On October 20th, 2024, Moldova will hold a referendum on enshrining Moldova’s EU ambitions in the constitution. However, several issues remain to be solved, for Moldova to enter the EU.

With a small and declining population of only about 2.5 million people and a GDP of 16.54 billion US dollars (2023), Moldova remains among the poorest countries in Eastern Europe. In 2023 the GDP per capita was 6600 US dollars in exchange rate terms (substantially higher if using PPP-adjusted measures; World Bank, 2024a). In the last decade, the largest share of its GDP, about 60 percent, stemmed from activities in the services sector, and about 20 and 10 percent from the industrial and agricultural sectors, respectively (Statista, 2024). Despite substantial economic growth in the last decade (3.3 percent on average between 2016 and 2021) and recent reforms (largely under the presidency of Maia Sandu), Moldova remains highly dependent on financial assistance from abroad and remittances, the latter contributing to about 15 – 35 percent of Moldova’s GDP in the last two decades (World Bank, 2024b).

The COVID-19 pandemic and refugee flows caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have only intensified this dependence. Furthermore, these events excavated existing vulnerabilities in the Moldovan economy, such as high inflation and soaring energy and food prices, which depressed households’ disposable incomes and consumption, while war-related uncertainty contributed to weaker investment (World Bank, 2024c).

The Contested Region of Transnistria – Challenge for Moldova’s EU Integration

In addition to Moldova’s economic challenges, the country also faces a particular and unusual problem; it does not fully control its territory. The Transnistrian region in the North-West of the country (at the South-Western border of Ukraine) constitutes about 12 percent of Moldova’s territory. The region has a population of about 350 000 people, mostly Russian-speaking Moldovans, Russians, and Ukrainians.

Following the breakup of the Soviet Union, a movement for self-determination for the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic resulted in a self-declaration of its independence on the 2nd of September 1990. More specifically, the alleged suppression of the Russian language and threats of unification between Moldova and Romania were the main stated reasons for the Transnistrian movement for self-determination, which in turn led to the civil armed conflict in 1992 and a following ceasefire agreement (Government of Republic of Moldova, 1992). The main points of the agreement concern the stationing of Russia’s 14th Army in Transnistria, the establishment of a demilitarized security zone, and the removal of restrictions on the movement of people, goods, and services between Moldova and Transnistria. As of 1992, Transnistria is de-facto an entity under “Russia’s effective control” (Roșa, 2021).

Over the years, the interpretations of the conflict have become more controversial, ranging from the local elite’s perspectives to assertions of an entirely artificial conflict fueled by malign Russian influence (Tofilat and Parlicov, 2020).

Notably, the Moldovan government has never officially recognized Transnistria as an occupied territory (see Article 11 of the Moldovan constitution stating “The Republic of Moldova – a Neutral State (1) The Republic of Moldova proclaims its permanent neutrality. (2) The Republic of Moldova shall not allow the dispersal of foreign military troops on its territory” (Constitute, 2024)).

Furthermore, the European Council’s official recognition of Transnistria as an “occupied territory” on March 15, 2022, underscores the EU’s stance on the matter and highlights Russia’s pivotal role in providing political, economic, and military support to Transnistria (PACE, 2022).

The Transnistrian Economy: Main Indicators and Weaknesses

Despite Russia’s central role in Transnistria, the region’s economy is, in practice, substantially integrated into the Moldovan and EU economies. This fact should be considered at various levels of decision-making when discussing Moldova’s EU accession.

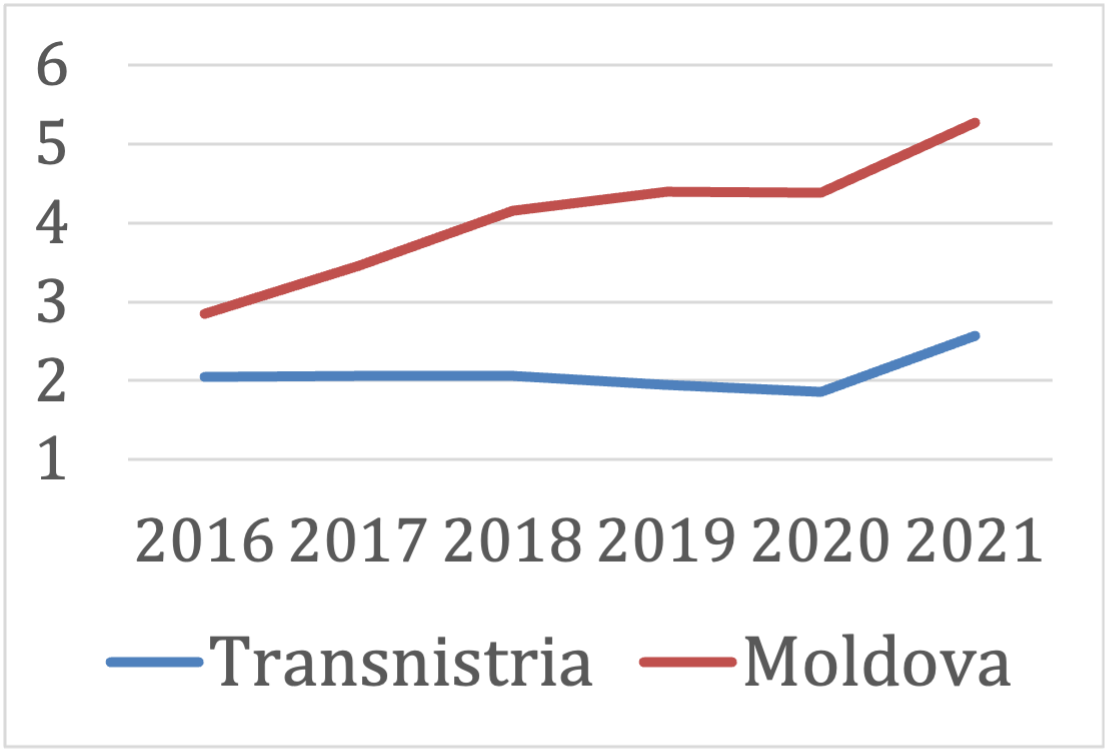

As depicted in Figure 1, economic activity in Transnistria has been quite “stable” in the last decade. GDP per capita has remained around 2000 US dollars, 2,5 times lower than Moldova’s GDP per capita in 2021.

Figure 1. Moldovan and Transnistrian GDP per capita, in thousand USD

Source: Data from World Bank, 2024; Pridnestrovian Republican Bank, 2024a. Note: since 2022 the Pridnestrovian Republican Bank has suspended publishing official statistics on macroeconomic indicators.

However, one must be careful when estimating and interpreting Transnistrian economic indicators in dollar terms. The local currency is the Transnistrian ruble which is not recognized anywhere in the world except in Russia. Its real value is thus highly uncertain as there is no market for this currency. Moreover, only Russian banks are authorized to open accounts and conduct transactions in the currency, demonstrating yet another significant weakness for Transnistria as a potential independent state, particularly given the current global ban on most Russian banks. As such, the official exchange rate for US dollars should be taken with a grain of salt. At the same time, there are no alternative statistics as the Pridnestrovian Republican Bank is the only source for relevant data on Transnistria.

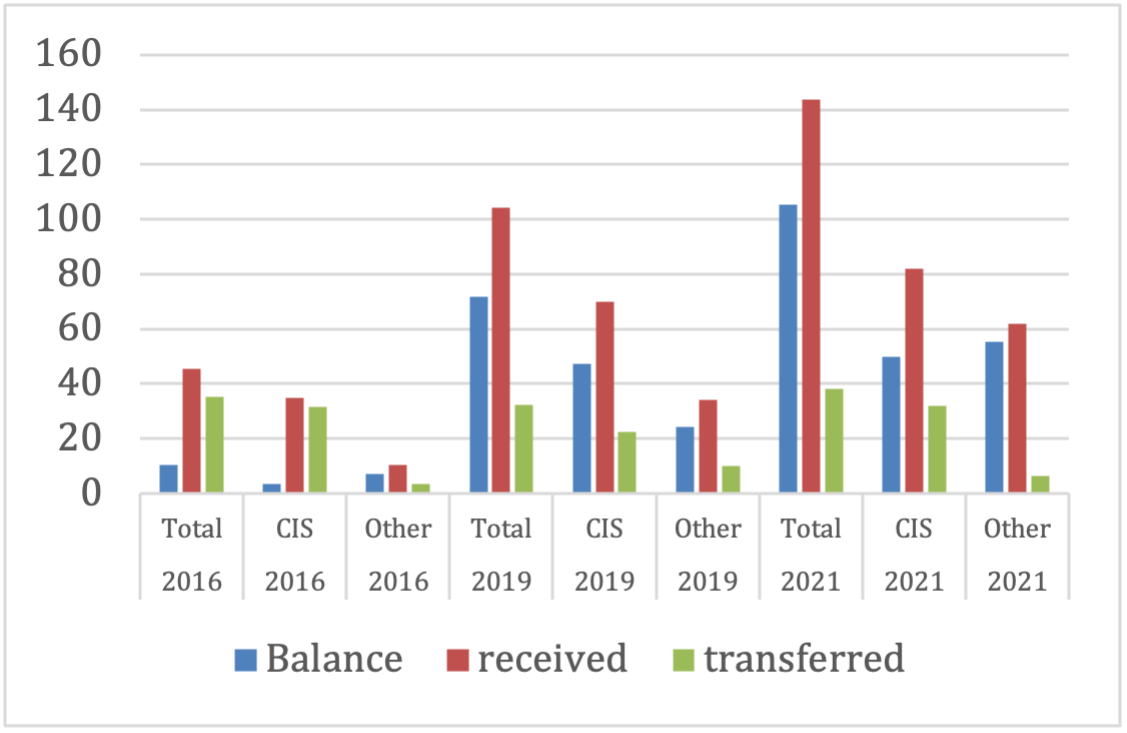

Another distinctive feature of Transnistria is the substantial reliance on remittances from abroad (see Figure 2). In 2021, remittances amounted to 143.7 million US dollars, constituting 15.5 percent of GDP in 2021 (if relying on the official exchange rate for US dollars, as published by the Pridnestrovian Republican Bank).

Figure 2. Remittances to/from Transnistria, in million USD

Source: Data from the Pridnestrovian Republican Bank (2024b). Note: CIS denotes the Commonwealth of Independent States and all other countries.

Figure 2 illustrates a notable trend of increasing dependency on remittances in recent years, particularly on remittances originating from CIS countries, chiefly Russia and Ukraine.

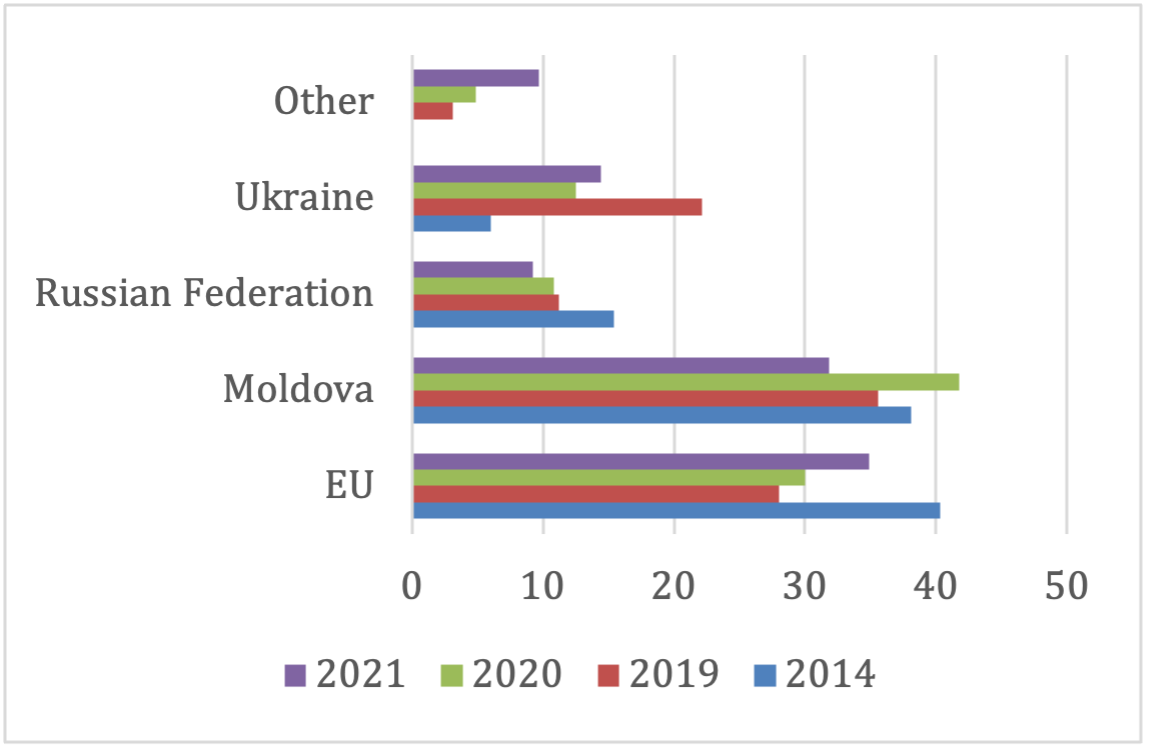

In terms of reliance on Russia, this dependency is not a concern when it comes to Transnistria’s exports. Foreign trade data from recent years indicates that the Transnistrian economy no longer relies on exports to Russia. As seen in Figure 3, the share of exports to Russia has been constantly declining since 2014 and amounted to merely 9.2 percent in 2021. At the same time, exports to the EU, Moldova and Ukraine collectively accounted for about 80 percent in 2021. The primary commodities driving Transnistrian exports were metal products, amounting to 337.3 million US dollars in 2021, followed by electricity supplies at 130.1 million US dollars. Additionally, food products and raw materials contributed 87.6 million US dollars to Transnistrian exports in the same period.

Figure 3. Transnistrian exports by destination countries, in percent

Source: Data from the Pridnestrovian Republican Bank Bulletins (2024c).

These figures highlight the significant integration of the Transnistrian economy into the European market and, to some extent, indicate the strong potential to further align in this direction.

The increase in Transnistria’s exports to the EU in recent years can be largely attributed to the implementation of mandatory registration of Transnistrian enterprises in Moldova in 2006 as a prerequisite for engaging in foreign economic activities (EUBAM, 2017). Consequently, Moldova has exercised full control over Transnistrian exports and partial control over its imports since 2006.

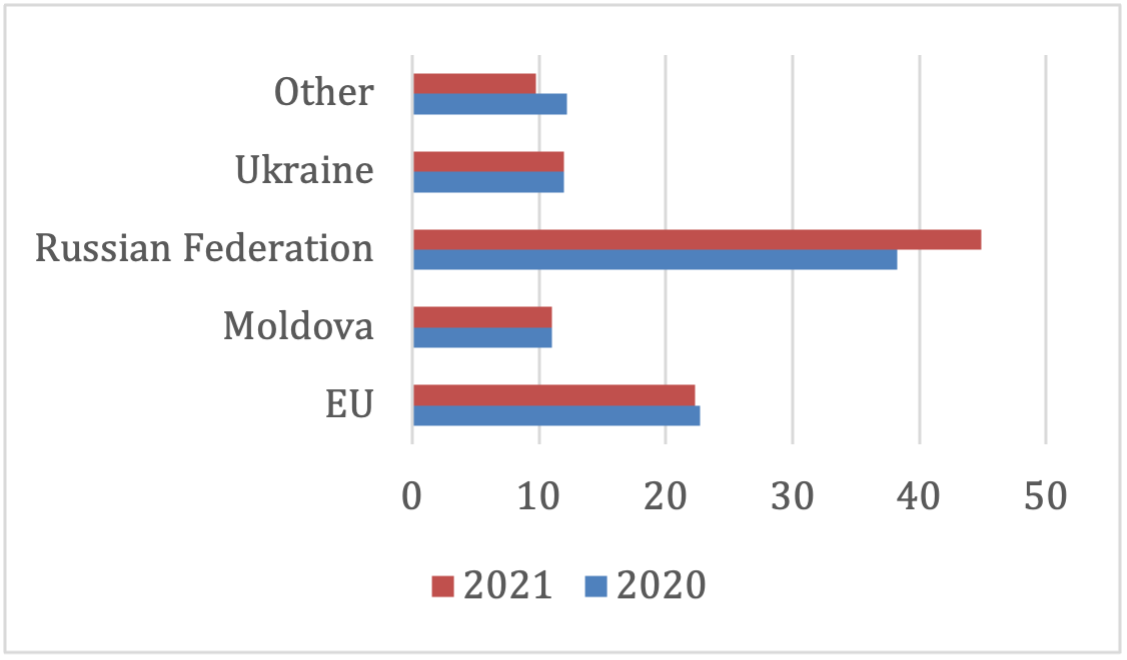

However, Transnistria remains reliant on Russia for its imports, particularly in the energy sector. In contrast to the export structure, Russia’s share in Transnistrian imports was significantly larger in 2021. About 45 percent of the imports originated from Russia in 2021, and mostly constituted of fuel and energy goods (447.0 million US dollars) and metal imports (254.3 million US dollars), quite typical for a transition economy.

Figure 4. Transnistrian imports by origin countries, in percent

Source: Data from the Pridnestrovian Republican Bank Bulletins (2024c).

Transnistria’s Energy Dependence on Russia

The biggest challenge for Transnistria, as well as for Moldova, is the large fuel and energy dependence on Russia, mostly in the form of natural gas.

For many years, gas has been supplied to Transnistria effectively for free, often in the form of a so-called “gas subsidy” (Roșa, 2021). This gas flows through Transnistria to Moldova, effectively accumulating a gas debt. Typically, Gazprom supplies gas to Moldovagaz, which in turn distributes gas to Moldovan consumers and to Tiraspol-Transgaz in Transnistria. Tiraspol-Transgaz then resell the gas at subsidized tariffs to local Transnistrian households and businesses. This included providing gas to the Moldovan State Regional Power Station, also known as MGRES – the largest power plant in Moldova. MGRES, in turn, exports electricity, further highlighting the interconnectedness of energy distribution between the Transnistrian region and the rest of Moldova.

Figure 5. Export/import of fuel and energy products from/to Transnistria, in million USD

Source: Data from the Pridnestrovian Republican Bank Bulletins (2024c). Note: Data for 2017 and 2018 unavailable.

The revenue generated from energy exports to Moldova has been deposited into a so-called special gas account and subsequently channeled directly into the Transnistrian budget in the form of loans from Tiraspol-Transgaz. In this way the Transnistrian government has covered more than 30 percent of their total budgetary expenditures over the last ten-year period. This further points to Transnistria’s’ fiscal inefficiencies and highlights its precarious dependency on gas from the Russian Federation.

In the last few years there have however been repeated disruptions in the gas supply and continuous disputes about prices and how much Moldovagaz owes Gazprom. De jure Tiraspol-Transgaz operates as a subsidiary of Moldovagaz, but de facto its assets were effectively nationalized by the separatist authorities in Transnistria (Tofilat and Parlicov, 2020). These unclarities has led to multiple conflicts over who owes the built-up gas debt. Given the ownership structure the debt is often seen as “Moldovan debt to Russia” (see e.g., Miller, 2023), albeit created by Transnistrian authorities. According to Gazprom, the outstanding amount owed by Moldovagaz to Gazprom stood at approximately 8 billion USD at the end of 2019 (Gazprom, 2024). This corresponds to about 7 times of Transnistria’s GDP. The Moldavian assessment of the debt is about two orders of magnitude lower (Gotev, 2023).

The disagreement on the debt amount was the official reason for the gas supply to be drastically reduced in October 2022. From December 2022 to March 2023, Russia’s Gazprom supplied gas only to Transnistria and it was not until March 2023 that supplies to the rest of Moldova were resumed. Since then, there have been shifts back and forth with Moldova mainly buying gas from Moldovan state-owned Energocom, which imports gas from suppliers other than Gazprom (Całus, 2023; Tanas, 2023). Understanding all turns and events is at times challenging due to lack of transparency in dealings.

Currently, despite Gazprom’s debt claims, the entirety of Transnistria’s gas is still being provided by Russia. While this is a relatively “cheap” investment from the Russian perspective, its impact on Moldova is large, as highlighted by Tofilat and Parlicov (2020) “the bottomline costs for Russia with maintaining Transnistria as its main instrument of influence in Moldova was at most USD 1 billion—not too expensive for twenty-seven years of influence in a European country of 3 million people”.

Corruption in Transnistria – Who is the Real “Sheriff”?

Another obstacle hindering a resolution of the Transnistrian conflict is the near complete monopoly of political and economic power held by Transnistria’s former President Igor Smirnov (1991-2011), through his strong ties to the Sheriff corporation. The corporation, established in 1993 by two former members of Transnistria’s “special services” (Ilya Kazmaly and Victor Gushan), was enabled by Transnistria’s former president, Igor Smirnov. For instance, the Sheriff company was exempt from paying customs duties and was permitted to monopolize trade, oil, and telecommunications in Transnistria. In return, the company supported Smirnov’s party during his presidency. For more on the conflict between Transnistria’s power clans and their relationships with Russia, see Hedenskog and Roine (2009) and Wesolowsky (2021).

The Sheriff company encompasses supermarkets, gas stations, construction firms, hotels, a mobile phone network, bakeries, a distillery, and a mini media empire comprising radio and TV stations. Presently, the company is reported to exert control over approximately 60 percent of the region’s economy (Wesolowsky, 2021).

A straightforward illustration of Sheriff’s political influence is the establishment of the Sheriff football team. For the team, Victor Gushan constructed the Sheriff sports complex, the largest football stadium in Moldova, accommodating

12 746 spectators. This investment in sports infrastructure is notable, especially considering that the total population of Transnistria is only approximately 350 000, and that the region is fairy poor. A similar example concerns the allocation of a land plot of 6.4 hectares to the company “to expand the construction of sports complex for long-term use under a simplified privatization procedure” signed directly by the former president.

While these details may seem peripheral to broader problems, they illustrate how some vested interests in the Transnistrian region may not be keen to change towards a society based on the rule-of-law, increased transparency and a market-oriented economy.

Moldova’s Options for Resolving the Transnistrian Conflict in EU Integration

As Moldova grapples with both the consequences of the ongoing conflict in Ukraine and the prolonged “frozen” conflict with Transnistria, its economy remains vulnerable. With the recent attainment of EU candidate status, it’s essential for the Moldovan government to map out ways to solve the conflict despite strong interest from powerful political and economic groups in preserving the status quo.

While the perspectives of resolving the Transnistrian conflict obviously hinge on Russian troops withdrawing from the region, Moldova would also need to address a wide range of economic issues. The Transnistrian economy faces numerous critical structural challenges including a persistent negative foreign trade balance, an unsustainable banking system, and pervasive corruption. Notably, the dominant oligarchic entity, the Sheriff company, exercises monopolistic political and economic influence, striving to preserve the status quo for Transnistria. The obvious unviability of the local currency due to its artificial nature and a complete dependency on Russia’s banking system are additional challenges to be solved for Moldova to be able to integrate Transnistria properly into its economy. Therefore, introducing additional measures such as restricting access to remittances in Transnistria, and imposing personal sanctions on elite groups could help Moldova in establishing economic control over the region.

Furthermore, while the Transnistrian region de-facto has strong economic ties with the Moldovan and European markets in terms of exports, its heavy reliance on Russian gas imports remains a significant vulnerability.

When integrating Transnistria and severing its ties with Russia, Moldova would also need to resolve the issues arising from its reliance on the electricity produced at MGRES using subsidized Russian gas. Natural gas bought at market prices would make Moldovan electricity highly costly, presenting financial challenges to Moldova, and effectively destroying the competitive advantage and important source of revenue in the Transnistrian region. Moreover, alternative electricity routes to Moldova are yet to be completed (with an estimated cost of approximately 27 million EUR).

These and other issues need to be dealt with for a successful Moldovan transition into the EU. Although these challenges are highly important from a Moldovan point of view, and even more so from a Transnistrian perspective, it should be emphasized that these issues are, in economic terms, relatively small for the EU. Given that the EU has opened the way for Moldovan accession, it should be ready to step up financially to help Moldova solve these issues and stay on the membership path.

References

- Całus, K. (2023, June 15). Moldova: diversifying supplies and curbing Gazprom’s influence. OSW Centre for Eastern Studies. https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/analyses/2023-06-15/moldova-diversifying-supplies-and-curbing-gazproms-influence

- Constitute. (2024). Constitution of Moldova (Republic of) 1994 (revision 2016). Https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Moldova_2016

- European Council. (2024, June 25). EU opens accession negotiations with Moldova. https://neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/news/eu-opens-accession-negotiations-moldova-2024-06-25_en

- European Parliament. (2022, June 23). Grant EU candidate status to Ukraine and Moldova without delay. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20220616IPR33216/grant-eu-candidate-status-to-ukraine-and-moldova-without-delay-meps-demand

- European Union Border Assistance Mission to Republic of Moldova and Ukraine (EUBAM). (2017). ENPI 2008 C2008 3821 RAP East EUBAM 6. https://neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2017-03/enpi_2008_c2008_3821_rap_east_eubam_6.pdf

- Gazprom. (2024). Gazprom financial report for Q4/2019. https://www.gazprom.ru/f/posts/77/885487/gazprom-ifrs-2019-12m-ru.pdf

- Gotev, G. (2023, September 7). Moldova puts its debt to Gazprom at $8.6 million, Russia disagrees. EURACTIV. https://www.euractiv.com/section/energy-environment/news/moldova-puts-its-debt-to-gazprom-at-8-6-million-russia-disagrees/

- Government of Republic of Moldova. (1992, July 21). Agreement on Principles of Peaceful Settlement of the Armed Conflict in the Transnistrian Region of Moldovan Republic. https://gov.md/sites/default/files/1992-07-21-ru-moscow-agr_on_principles_of_peaceful_settlem.pdf

- Hedenskog, J., & Roine, J. (2009). Transnistrien. En Ekonomisk och Säkerhetspolitisk Analys. Utrikesdepartementet/Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Sweden. Stockholm, 40 p.

- Leontiev, L. (2022, March 25). Big, But Distant Dreams. Political and Legal Implications of Moldova’s Quest for EU Membership. The Review of Democracy. https://revdem.ceu.edu/2022/03/25/big-but-distant-dreams-political-and-legal-implications-of-moldovas-quest-for-eu-membership/

- Miller, M. (2023, September 7). Independent Audit of Gazprom’s Debt Claims Against Moldovagaz. U.S. Embassy in Moldova. https://md.usembassy.gov/independent-audit-of-gazproms-debt-claims-against-moldovagaz/

- Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE). (2022, March 15). Consequences of the Russian Federation’s aggression against Ukraine. https://pace.coe.int/en/files/29885/html

- Pridnestrovian Republican Bank. (2024a). Main macroeconomic parameters of PMR. https://www.cbpmr.net/content.php?Id=13&lang=ru

- Pridnestrovian Republican Bank (2024b). Remittances. https://www.cbpmr.net/content.php?Id=110&lang=ru

- Pridnestrovian Republican Bank (2024c). Pridnestrovian Republican Bank Bulletins. https://www.cbpmr.net/content.php?Id=28&lang=ru

- Racz, A. (2016, April 8). The Frozen Conflicts of the EU’s Eastern Neighbourhood and Their Impact on the Respect of Human Rights. European Parliament Think Tank. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EXPO_STU(2016)578001

- Roșa, V. (2021, October 18). The Transnistrian Conflict: 30 Years Searching for a Settlement. SCEEUS Reports on Human Rights and Security in Eastern Europe No.4. https://sceeus.se/publikationer/the-transnistrian-conflict-30-years-searching-for-a-settlement/

- Statista. (2024). Moldova: Distribution of gross domestic product (GDP) across economic sectors from 2012 to 2022. https://www.statista.com/statistics/513314/moldova-gdp-distribution-across-economic-sectors/

- Tanas, A. (2023, March 21). Moldova resumes gas purchases from Russia’s Gazprom -Moldovagaz head. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/moldova-resumes-gas-purchases-russias-gazprom-moldovagaz-head-2023-03-21/

- Tofilat, S., & Parlicov, V. (2020, August 14). Russian Gas and the Financing of Separatism in Moldova. The Kremlin’s Influence Quarterly #2. https://www.4freerussia.org/russian-gas-and-the-financing-of-separatism-in-moldova/

- Wesolowsky, T. (2021, October 18). The Shadow Business Empire Behind the Meteoric Rise of Sheriff Tiraspol. RadioFreeEurope. https://www.rferl.org/a/moldova-sheriff-tiraspol-murky-business/31516518.html

- World Bank. (2024a). Data. Moldova. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD?Locations=MD

- World Bank. (2024b). Personal remittances, received (% of GDP) – Moldova. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.TRF.PWKR.DT.GD.ZS?Locations=MD

- World Bank. (2024c). Moldova Overview. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/moldova/overview

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in policy briefs and other publications are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect those of the FREE Network and its research institutes.

How to Intensify and Diversify Ukrainian Exports? The Case of Bilateral Trade with Germany

This policy brief focuses on trade relations between Ukraine and Germany. In particular, it analyses bilateral trade in goods and examines the possibilities for increasing Ukrainian exports to Germany, in both the extensive and the intensive margins. The brief identifies prospective product groups for such increases and discusses potential obstacles to trade intensification. Finally, it provides recommendations for the further trade development.

German-Ukrainian Trade

Germany has recently become one of the most important trading partners for Ukraine. In 2018, Germany was fifth in terms of Ukrainian export destinations and third in terms of its import source countries. While Ukraine, not surprisingly, is less important for German international trade (in 2018, Ukraine ranked 42nd in terms of Germany’s export and 45th in terms of its import), bilateral trade between Ukraine and Germany showed positive dynamics over the last five years.

Since Germany is a member of the European Union, its trade relations with Ukraine are regulated by legislation common for all EU member states. The EU’s political and economic cooperation with Ukraine is stipulated by the Association Agreement (AA). The AA is a comprehensive agreement provisioning the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA) between Ukraine and the EU. While the provisional application of the AA began in the fall of 2014, the document fully entered into force on September 1, 2017. The abovementioned intensification of trade relations between Ukraine and Germany was to a significant extent driven by the signing of the DCFTA and a loss of a significant share of the Russian market.

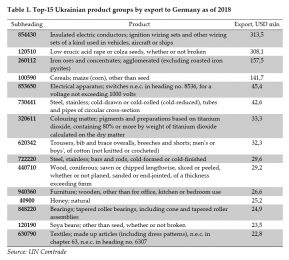

The main Ukrainian exports to Germany include ignition wiring sets used in vehicles, aircraft and ships; low erucic acid, rape or colza seeds, iron ores agglomerated, maize, electrical switches etc. (see Table 1). Together, the top-15 product groups at a 6-digit level of the Harmonised System (HS) give 57% of the total exports from Ukraine to Germany.

Table 1. Top-15 Ukrainian product groups by export to Germany as of 2018

Source: UN Comtrade

This brief argues that both countries are likely to gain additional benefits from further intensifying bilateral trade relations. It summarizes the results of the research (Iavorskyi P. at al., 2019) on how to further expand and diversify Ukrainian exports to Germany, it identifies the prospective product groups and obstacles to their exports, and provides policy recommendations for trade development.

Promising Products

In order to find the most promising ways for increasing Ukrainian exports to Germany, this study employs a two-step approach. First, using a normalized revealed comparative advantage (NRCA) index (Run Yu et al, 2009) we distinguish goods, which Ukraine has world-wide comparative advantage in and Germany does not. A positive (negative) NRCA indicates that country’s actual share of a product in national exports is higher (lower) than the world average, – so that the country has a comparative advantage (disadvantage) in this commodity. According to this criterion, product groups with a negative NRCA for Germany and a positive NRCA for Ukraine were selected.

At the second stage, for the goods identified during the first step, a gravity model was estimated. A gravity model predicts bilateral trade flows based on the size of the economy and trade costs between them (such as distance, cultural differences, free trade agreements, tariffs, etc.). Being a general equilibrium model, it captures not only immediate impact of economic and political changes on trade between two countries, but also how it influences trade with other countries. A gap between current and potential export volumes predicted by the model is a potential for exports increase (which we refer to as undertrade).

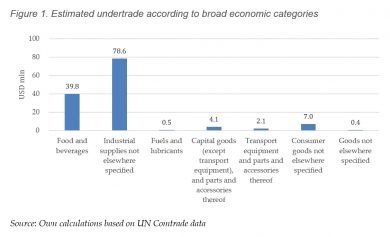

The gravity model estimates the total undertrade between Ukraine and Germany at $ 500 million in 2016, or 35% of the total exports from Ukraine to Germany in the same year. Moreover, Ukraine has the potential to increase trade in both goods already exported to Germany as well as goods not yet supplied by Ukrainian companies to this market.

As for the structure of our findings, agricultural and mining commodities, as well as products of traditional Ukrainian export industries, such as metallurgy, are widely represented on the top of the undertraded commodity list. For example, more than a half of the estimated undertrade falls on primary food and primary industrial supplies, such as soybeans, barley, tomatoes, grain sorghum, iron ore, zirconium ores, etc. These categories already account for a large share of the current exports composition, and production in these sectors provides for a significant share of employment. Foreign currency inflow stipulated by exporting these products is also important for the Ukrainian economy.

At the same time, the undertrade in categories of final consumption, capital goods and transport is much lower. However, these product groups are important for exports diversification. These, for example, include liquid dielectric transformers, refrigerator cabinets, telescopes, tugs and pusher craft in capital goods, rail locomotives, railway cars, gas turbine engines in transport; automatic washing machines, electric space heaters, fans, coffeemakers, synthetic curtains, and leather apparel in consumer goods. Despite the complex regulation and relatively small amount of estimated undertrade, export diversification from primary to manufactured goods is important for overcoming export instability and long-term economic growth (Cadot at al. 2013), which is why promotion of trade in such areas is important.

Figure 1. Estimated undertrade according to broad economic categories

Source: Own calculations based on UN Comtrade data

Obstacles to Trade

Following the abolition or reduction of EU import duties between Ukraine and the EU under the DCFTA, tariffs do not significantly restrict exports of Ukrainian goods to the EU. Instead, technical regulations, sanitary and phytosanitary measures, geographical indications, licensing, etc. create significant barriers to bilateral trade. Thus, “non-tradability” can be explained, for instance, by the negative effects of various non-tariff barriers (both at European and national levels) or other factors, such as low competitiveness (in terms of price or quality) of Ukrainian goods compared to similar goods supplied by other countries, taste preferences of German consumers, peculiarities of importers’ associations, specific requirements of retailers, etc. Thus, harmonization of Ukrainian regulations with those of the European Union in accordance with the AA will help reduce customs barriers and existing divergences in regulations, and thus simplify the export of Ukrainian goods to the EU and Germany in particular.

Policy Recommendations

Based on the findings of the qualitative and quantitative research carried out, Ukrainian policy makers are advised to:

- Timely and effectively align Ukrainian legislation, standards and practices with those of the EU, in line with the Action Plan and Commitments undertaken by Ukraine under the DCFTA within the framework of the AA with the EU, in particular in such areas as technical barriers to trade, sanitary and phytosanitary measures, customs, and protection of intellectual property rights.

- Accelerate preparations for the signing of the ACAA (the Agreement on Conformity Assessment and Acceptance for Industrial Products) for the top three priority sectors of Ukrainian industry, which Ukrainian authorities agreed with European side, namely in the areas of low-voltage equipment, electromagnetic compatibility and machine safety, which will boost industrial technological exports to the EU and other countries.

- Conduct government level negotiations with the EU and Germany regarding the removal of those barriers to the single market faced by the promising Ukrainian goods that will not be lifted as a result of harmonization of regulations with the European ones.

- Take advantage of the Regional Pan-Euro-Mediterranean Preferential Rules of Origin Convention (the Pan-Euro-Med Convention), which establishes identical rules of origin for goods between its member-states under free trade agreements, and will facilitate the opening of new production facilities and involvement in regional and international value chains.

- Provide information and consulting support to local manufacturers and exporters regarding the most promising destination markets, help them find partners on such markets, advise on the best ways to penetrate such markets by organizing trade missions, etc.

Another push to the German-Ukrainian trade promotion may arise from facilitating German FDIs to Ukraine. German entrepreneurs and investors are interested in localizing German production facilities in Ukraine and establishing joint German-Ukrainian enterprises, STIs, in particular in such areas as agriculture, light industry (including textiles), civil engineering, renewable energy, and circular economy (GTAI 2018a, 2018b, 2018c). This form of cooperation also boosts Ukrainian exports, since such enterprises often produce intermediate inputs for German production. In order to promote joint enterprises setup Ukraine should:

- Establish effective mechanisms for protecting foreign investments, including export-oriented ones.

- Ensure the rule of law and effective protection of property rights.

- Create favorable macroeconomic conditions to ensure access to financing for both Ukrainian and foreign businesses.

References

- Cadot O., Carrère C., and V. Strauss‐Kahn, 2013. Trade Diversification, Income, and Growth: What Do We Know? Journal of Economic Surveys 27(4): 790-812

- Germany Trade & Invest (GTAI) (2018a). Branche kompakt: Ukrainischer Maschinenbau profitiert von steigenden Investitionen. Accessed online October 14, 2019.

- Germany Trade & Invest (GTAI) (2018b). Ukraine hat hohen Bedarf an moderner Landtechnik. Accessed online October 14, 2019.

- Germany Trade & Invest (GTAI) (2018c). Ukrainischer Markt für Windenergie im Aufwind. Accessed online October 14, 2019.

- Iavorskyi P. at al., 2019. “How to grow and diversify Ukrainian exports to Germany? Analysis and Recommendations” (in Ukrainian). Working paper

- Yu, R., Cai, J. & Leung, P. 2009. Ann Reg Sci, 43: 267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-008-0213-3

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in policy briefs and other publications are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect those of the FREE Network and its research institutes.

“New Goods” Trade in the Baltics

We analyze the role of the new goods margin—those goods that initially account for very small volumes of trade—in the Baltic states’ trade growth during the 1995-2008 period. We find that, on average, the basket of goods that in 1995 accounted for 10% of total Baltic exports and imports to their main trade partners, represented nearly 50% and 25% of total exports and imports in 2008, respectively. Moreover, we find that the share of Baltic new-goods exports outpaced that of other transition economies of Central and Eastern Europe. As the International Trade literature has recently shown, these increases in newly-traded goods could in turn have significant implications in terms of welfare and productivity gains within the Baltic economies.

New EU members, new trade opportunities

The Eastern enlargements of the European Union (EU) that have taken place since 2004 included the liberalization of trade as one of their main pillars and consequently provided new opportunities for the expansion of trade among the new and old members. Growth in trade following trade liberalization episodes such as the ones contemplated in the recent EU expansions could occur because of two reasons. First, because countries export and import more of the goods that they had already been trading. Alternatively, trade liberalization could promote the exchange of goods that had previously not been traded. The latter alternative is usually referred to as increases in the extensive margin of trade, or the new goods margin.

The new goods margin has been receiving a considerable amount of attention in the International Trade literature. For example, Broda and Weinstein (2006) estimate the value to American consumers derived from the growth in the variety of import products between 1972 and 2001 to be as large as 2.6% of GDP, while Chen and Hong (2012) find a figure of 4.9% of GDP for the Chinese case between 1997 and 2008. Similarly, Feenstra and Kee (2008) find that, in a sample of 44 countries, the total increase in export variety is associated with an average 3.3% productivity gain per year for exporters over the 1980–2000 period. This suggests that the new goods margin has significant implications in terms of both welfare and productivity.

In a forthcoming article (Cho and Díaz, in press) we study the patterns of the new goods margin for the three Baltic states: Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. We investigate whether the period of rapid trade expansion experienced by these countries after gaining independence in 1991—average exports grew by more than 700% between 1995 and 2008 in nominal terms, and average imports by more than 800%—also coincided with increases in newly-traded goods by quantifying the relative importance of the new goods margin between 1995 and 2008. This policy brief summarizes our results.

Why focus on the Baltics?

The Baltic economies present an interesting case for a series of reasons. First, along a number of dimensions, the Baltic countries stood out as leaders among the formerly centrally-planned economies in implementing market- and trade-liberalization reforms. Indeed, those are the kind of structural changes that Kehoe and Ruhl (2013) identify as the main drivers of extensive margin increases. Second, unlike other transition economies, as part of the Soviet Union the Baltics lacked any degree of autonomy. Thus, upon independence, they faced a vast array of challenges, among them the difficult task of establishing trade relationships with the rest of the world, which prior to 1991 were determined solely from Moscow. Lastly, as former Soviet republics, the Baltic states had sizable portions of ethnic Russian-speaking population, most of which remained in the Baltics even after their independence. At least in principle, this gave the Baltic economies a unique potential to better tap into the Russian market.

Defining “new goods”

We use bilateral merchandise trade data for Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania starting in 1995 and ending in 2008, the year before the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). The data are taken from the World Bank’s World Integrated Trade Solution database. The trade data are disaggregated at the 5-digit level of the SITC Revision 2 code, which implies that our analysis deals with 1,836 different goods.

To construct a measure of the new goods margin, we follow the methodology laid out in Kehoe and Ruhl (2013). First, for each good we compute the average export and import value during the first three years in the sample (in our case, 1995 to 1997), to avoid any distortions that could arise from our choice of the initial year. Next, goods are sorted in ascending order according to the three-year average. Finally, the cumulative value of the ranked goods is grouped into 10 brackets, each containing 10% of total trade. The basket of goods in the bottom decile is labeled as the “new” goods or “least-traded” goods, since it contains goods that initially recorded zero trade, as well as goods that were traded in positive—but low—volumes. We then trace the evolution of the trade value of the goods in the bottom decile, which represents the growth of trade in least-traded goods.

Findings

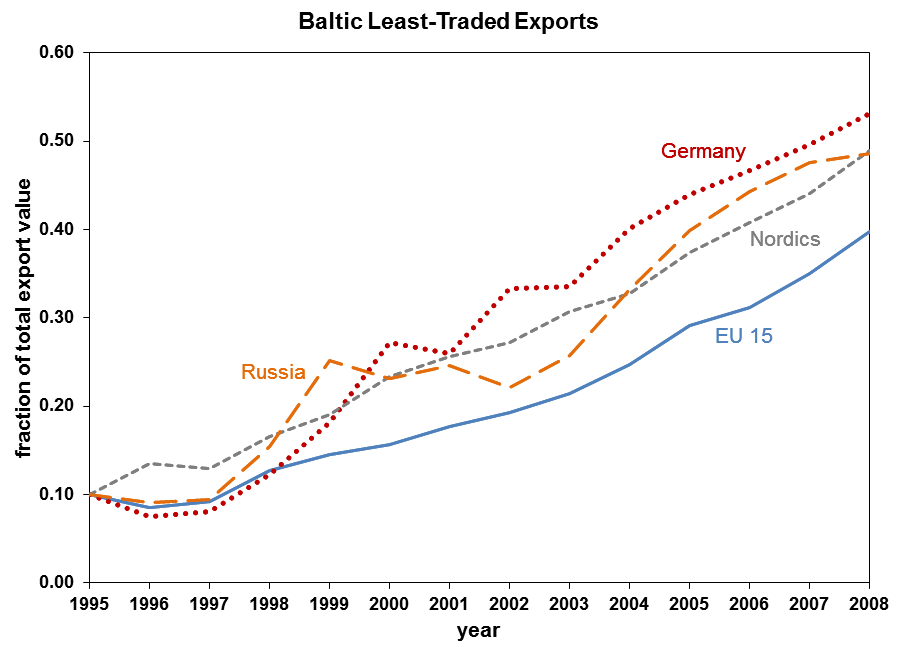

For ease of exposition, we present the results for the average Baltic exports and imports of least-traded goods, rather than the trade flows for each country. Results for each individual country can be found in Cho and Díaz (in press). We report the least-traded exports and imports to and from the Baltics’ main trade partners: the EU15, composed of the 15-country bloc that constituted the EU prior to the 2004 expansion; Germany, which within the EU15 stands out as the main trade partner of Latvia and Lithuania; the “Nordics”, a group that combines Finland and Sweden, Estonia’s largest trade partners; and Russia, because of its historical ties with the Baltic states and its relative importance in their total trade.

Least-traded exports

Figure 1 shows the evolution over time of the share in total exports of the goods that were initially labeled as “new goods”, i.e., those products that accounted for 10% of total trade in 1995. We find that the Baltic states were able to increase their least-traded exports significantly, and by 2008 such exports accounted for nearly 40% of total exports to the EU15, and close to 53%, 49% and 49% of total exports to Germany, the Nordic countries, and Russia, respectively. Moreover, we find that the fastest growth in least-traded exports to the EU15 and its individual members coincided with the periods when the Association Agreements and accession to the EU took place. Finally, we discover that the rapid increase in least-traded exports to the EU15 during the late 1990s and early 2000s is accompanied by a stagnation of least-traded exports to Russia. This suggest that, as the Baltics received preferential treatment from the EU, they expanded their export variety mix in that market at the expense of the Russian. Growth in least-traded exports to Russia only resumed in the mid 2000s, when the Baltics became EU members and were granted the same preferential treatment in the Russian market that the other EU members enjoyed.

Figure 1. Baltic least-traded exports

Source: Cho and Díaz (in press).

Source: Cho and Díaz (in press).

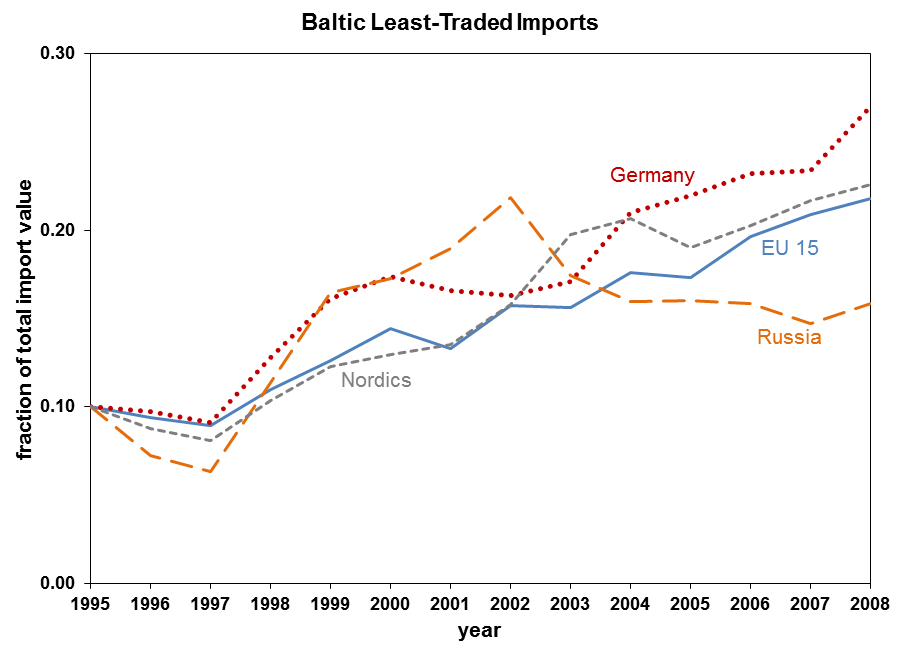

Least-traded imports

Figure 2 plots the evolution of Baltic least-traded imports between 1995 and 2008. We find that new goods imports also grew at robust rates, but their growth is about half the magnitude of the growth in the least-traded exports—the least-traded imports nearly doubled their share, whereas the least-traded exports quadrupled it. The least-traded imports from the EU15 and its individual members exhibited consistent growth throughout. On the other hand, imports of new goods from Russia—which had also been growing since 1995—started a continuous decline starting in 2003. This change in patterns can be attributed to the Baltics joining the EU customs union. Prior to their EU accession, the average Baltic tariff was in general low. Upon EU accession, the Baltics adopted the EU’s Commercial Common Policy, which removed trade restrictions for EU goods flowing into the Baltics, but—from the perspective of the Baltic countries—raised tariffs on non-EU imports, in turn discouraging the imports of Russian new goods.

Figure 2. Baltic least-traded imports

Source: Cho and Díaz (in press).

Source: Cho and Díaz (in press).

Are the Baltics different?

Figure 1 shows that the Baltic states were able to increase their least-traded exports by a significant margin. A natural question follows: Is this a feature that is unique of the Baltic economies, or is it instead a generalized trend among the transition countries?

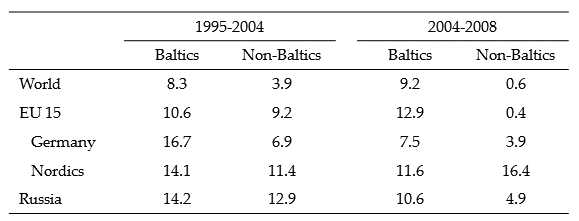

Table 1: Growth of the share of least-traded exports (percent, annual average)

Source: Cho and Díaz (in press).

Source: Cho and Díaz (in press).

Table 1 reveals that the new goods margin played a much larger role for the Baltic states than for other transition economies such as the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland (which we label as “Non-Baltics”), for all the export destinations we consider. Moreover, we find that while until 2004—the year of the EU accession—both Baltic and Non-Baltic countries displayed high and comparable growth rates of least-traded exports, this trend changed after 2004. Indeed, while there is no noticeable slowdown in the Baltic growth rate, after 2004 the Non-Baltic growth of least-traded exports to the world and to the EU15 all but stops, with the only exception being the Nordic destinations.

Conclusion

The Baltic states, and in particular Estonia, are usually portrayed as exemplary models of trade liberalization among the transition economies. Our results indicate that the Baltics substantially increased both their imports and exports of least-traded goods between 1995 and 2008. Since increases in the import variety mix have been shown to entail non-negligible welfare effects, we expect large welfare gains for the Baltic consumers experienced due to the increases in the imports of previously least-traded goods. Moreover, the literature has documented that increases in export variety are associated with increases in labor productivity. Our findings reveal that the Baltics’ increases in their exports of least-traded goods were even larger than their imports of new goods, thus underscoring the importance of the new goods margin because of their contribution to labor productivity gains.

References

- Broda, Christian; and David E. Weinstein, 2006. “Globalization and the gains from variety,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 121 (2), pp. 541–585.

- Chen, Bo; and Ma Hong, 2012. “Import variety and welfare gain in China,” Review of International Economics, Vol. 20 (4), pp. 807–820.

- Cho, Sang-Wook (Stanley); and Julián P. Díaz. “The new goods margin in new markets,” Journal of Comparative Economics, in press.

- Feenstra, Robert C.; and Hiau Looi Kee, 2008. “Export variety and country productivity: estimating the monopolistic competition model with endogenous productivity,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 74 (2), pp. 500–518.

- Kehoe, Timothy J.; and Kim J. Ruhl, 2013. “How important is the new goods margin in international trade?” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 121 (2), pp. 358–392.