Location: EU

Moldova’s EU Integration and the Special Case of Transnistria

In the shadow of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, another East European country is actively working to secure its European future. After three years of negotiating cooperation agreements with the European Commission, Moldova finally obtained its EU candidate status and is now on track to join the EU as a member state. However, among many remaining obstacles on the path to full membership, one stands out as especially problematic: the region of Transnistria. The region, officially Pridnestrovian Moldovan Republic, is an internationally unrecognized country and is rather seen as a region with which Russia has “special relations”, including a military presence in the region since 1992. This policy brief provides an overview of the current state of the Transnistrian economy and its relationships with Moldova, the EU, and Russia, arguing that Transnistria’s economy is de facto already integrated into the Moldovan and EU economies. It also points to the key challenges to resolve for a successful integration of Moldova into the EU.

Moldova’s EU Integration: The Moldovan Economy on its Path to EU Accession

On December 14th, 2023, the European Council decided to open accession negotiations with Moldova, recognizing Moldova’s substantial progress when it comes to anti-corruption and de-oligarchisation reforms. The first intergovernmental conference was held on the 25th of June 2024, officially launching accession negotiations (European Council, 2024). On October 20th, 2024, Moldova will hold a referendum on enshrining Moldova’s EU ambitions in the constitution. However, several issues remain to be solved, for Moldova to enter the EU.

With a small and declining population of only about 2.5 million people and a GDP of 16.54 billion US dollars (2023), Moldova remains among the poorest countries in Eastern Europe. In 2023 the GDP per capita was 6600 US dollars in exchange rate terms (substantially higher if using PPP-adjusted measures; World Bank, 2024a). In the last decade, the largest share of its GDP, about 60 percent, stemmed from activities in the services sector, and about 20 and 10 percent from the industrial and agricultural sectors, respectively (Statista, 2024). Despite substantial economic growth in the last decade (3.3 percent on average between 2016 and 2021) and recent reforms (largely under the presidency of Maia Sandu), Moldova remains highly dependent on financial assistance from abroad and remittances, the latter contributing to about 15 – 35 percent of Moldova’s GDP in the last two decades (World Bank, 2024b).

The COVID-19 pandemic and refugee flows caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have only intensified this dependence. Furthermore, these events excavated existing vulnerabilities in the Moldovan economy, such as high inflation and soaring energy and food prices, which depressed households’ disposable incomes and consumption, while war-related uncertainty contributed to weaker investment (World Bank, 2024c).

The Contested Region of Transnistria – Challenge for Moldova’s EU Integration

In addition to Moldova’s economic challenges, the country also faces a particular and unusual problem; it does not fully control its territory. The Transnistrian region in the North-West of the country (at the South-Western border of Ukraine) constitutes about 12 percent of Moldova’s territory. The region has a population of about 350 000 people, mostly Russian-speaking Moldovans, Russians, and Ukrainians.

Following the breakup of the Soviet Union, a movement for self-determination for the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic resulted in a self-declaration of its independence on the 2nd of September 1990. More specifically, the alleged suppression of the Russian language and threats of unification between Moldova and Romania were the main stated reasons for the Transnistrian movement for self-determination, which in turn led to the civil armed conflict in 1992 and a following ceasefire agreement (Government of Republic of Moldova, 1992). The main points of the agreement concern the stationing of Russia’s 14th Army in Transnistria, the establishment of a demilitarized security zone, and the removal of restrictions on the movement of people, goods, and services between Moldova and Transnistria. As of 1992, Transnistria is de-facto an entity under “Russia’s effective control” (Roșa, 2021).

Over the years, the interpretations of the conflict have become more controversial, ranging from the local elite’s perspectives to assertions of an entirely artificial conflict fueled by malign Russian influence (Tofilat and Parlicov, 2020).

Notably, the Moldovan government has never officially recognized Transnistria as an occupied territory (see Article 11 of the Moldovan constitution stating “The Republic of Moldova – a Neutral State (1) The Republic of Moldova proclaims its permanent neutrality. (2) The Republic of Moldova shall not allow the dispersal of foreign military troops on its territory” (Constitute, 2024)).

Furthermore, the European Council’s official recognition of Transnistria as an “occupied territory” on March 15, 2022, underscores the EU’s stance on the matter and highlights Russia’s pivotal role in providing political, economic, and military support to Transnistria (PACE, 2022).

The Transnistrian Economy: Main Indicators and Weaknesses

Despite Russia’s central role in Transnistria, the region’s economy is, in practice, substantially integrated into the Moldovan and EU economies. This fact should be considered at various levels of decision-making when discussing Moldova’s EU accession.

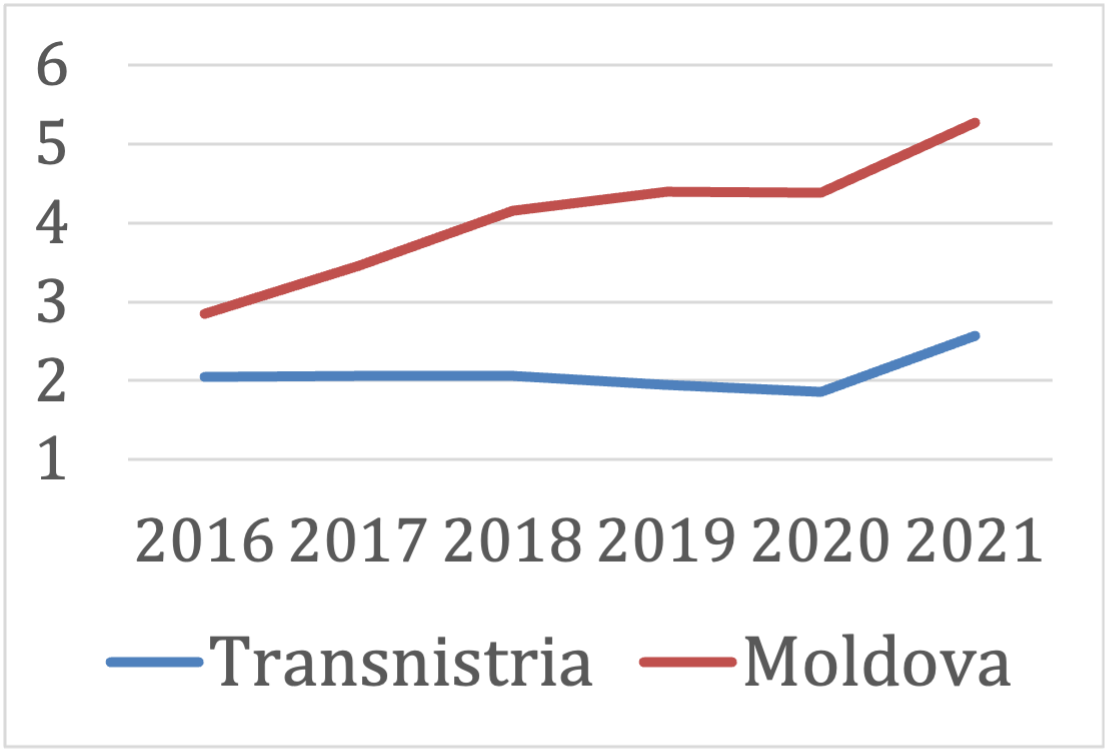

As depicted in Figure 1, economic activity in Transnistria has been quite “stable” in the last decade. GDP per capita has remained around 2000 US dollars, 2,5 times lower than Moldova’s GDP per capita in 2021.

Figure 1. Moldovan and Transnistrian GDP per capita, in thousand USD

Source: Data from World Bank, 2024; Pridnestrovian Republican Bank, 2024a. Note: since 2022 the Pridnestrovian Republican Bank has suspended publishing official statistics on macroeconomic indicators.

However, one must be careful when estimating and interpreting Transnistrian economic indicators in dollar terms. The local currency is the Transnistrian ruble which is not recognized anywhere in the world except in Russia. Its real value is thus highly uncertain as there is no market for this currency. Moreover, only Russian banks are authorized to open accounts and conduct transactions in the currency, demonstrating yet another significant weakness for Transnistria as a potential independent state, particularly given the current global ban on most Russian banks. As such, the official exchange rate for US dollars should be taken with a grain of salt. At the same time, there are no alternative statistics as the Pridnestrovian Republican Bank is the only source for relevant data on Transnistria.

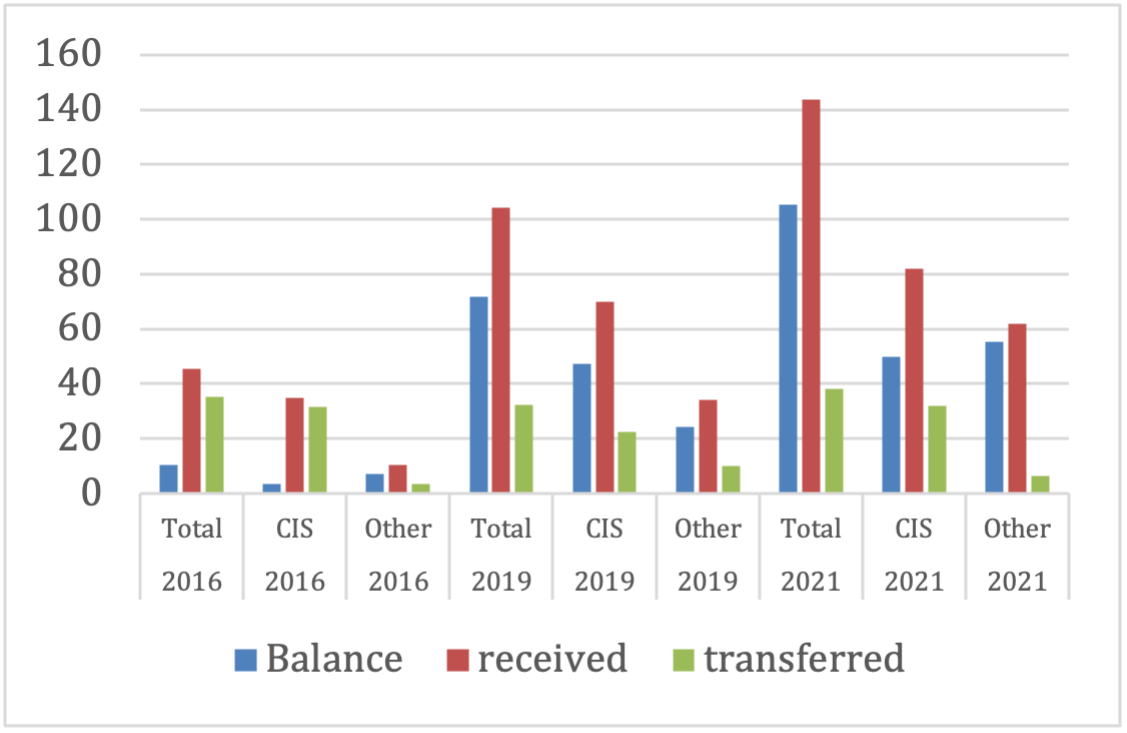

Another distinctive feature of Transnistria is the substantial reliance on remittances from abroad (see Figure 2). In 2021, remittances amounted to 143.7 million US dollars, constituting 15.5 percent of GDP in 2021 (if relying on the official exchange rate for US dollars, as published by the Pridnestrovian Republican Bank).

Figure 2. Remittances to/from Transnistria, in million USD

Source: Data from the Pridnestrovian Republican Bank (2024b). Note: CIS denotes the Commonwealth of Independent States and all other countries.

Figure 2 illustrates a notable trend of increasing dependency on remittances in recent years, particularly on remittances originating from CIS countries, chiefly Russia and Ukraine.

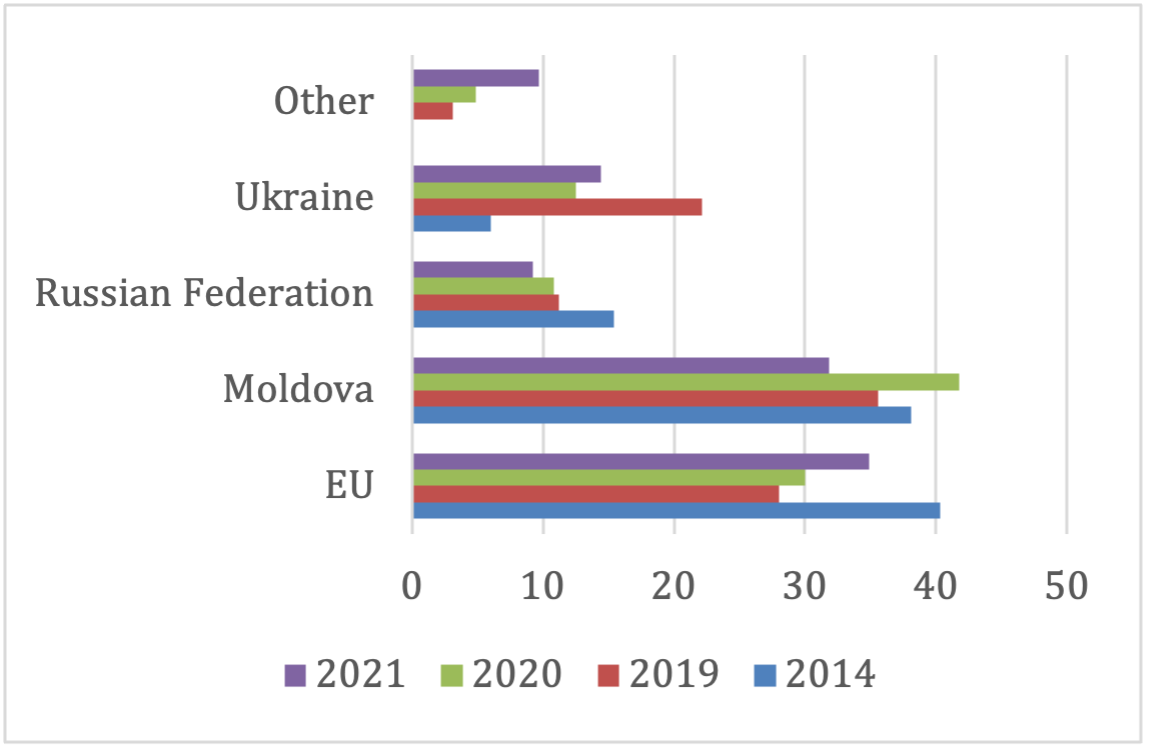

In terms of reliance on Russia, this dependency is not a concern when it comes to Transnistria’s exports. Foreign trade data from recent years indicates that the Transnistrian economy no longer relies on exports to Russia. As seen in Figure 3, the share of exports to Russia has been constantly declining since 2014 and amounted to merely 9.2 percent in 2021. At the same time, exports to the EU, Moldova and Ukraine collectively accounted for about 80 percent in 2021. The primary commodities driving Transnistrian exports were metal products, amounting to 337.3 million US dollars in 2021, followed by electricity supplies at 130.1 million US dollars. Additionally, food products and raw materials contributed 87.6 million US dollars to Transnistrian exports in the same period.

Figure 3. Transnistrian exports by destination countries, in percent

Source: Data from the Pridnestrovian Republican Bank Bulletins (2024c).

These figures highlight the significant integration of the Transnistrian economy into the European market and, to some extent, indicate the strong potential to further align in this direction.

The increase in Transnistria’s exports to the EU in recent years can be largely attributed to the implementation of mandatory registration of Transnistrian enterprises in Moldova in 2006 as a prerequisite for engaging in foreign economic activities (EUBAM, 2017). Consequently, Moldova has exercised full control over Transnistrian exports and partial control over its imports since 2006.

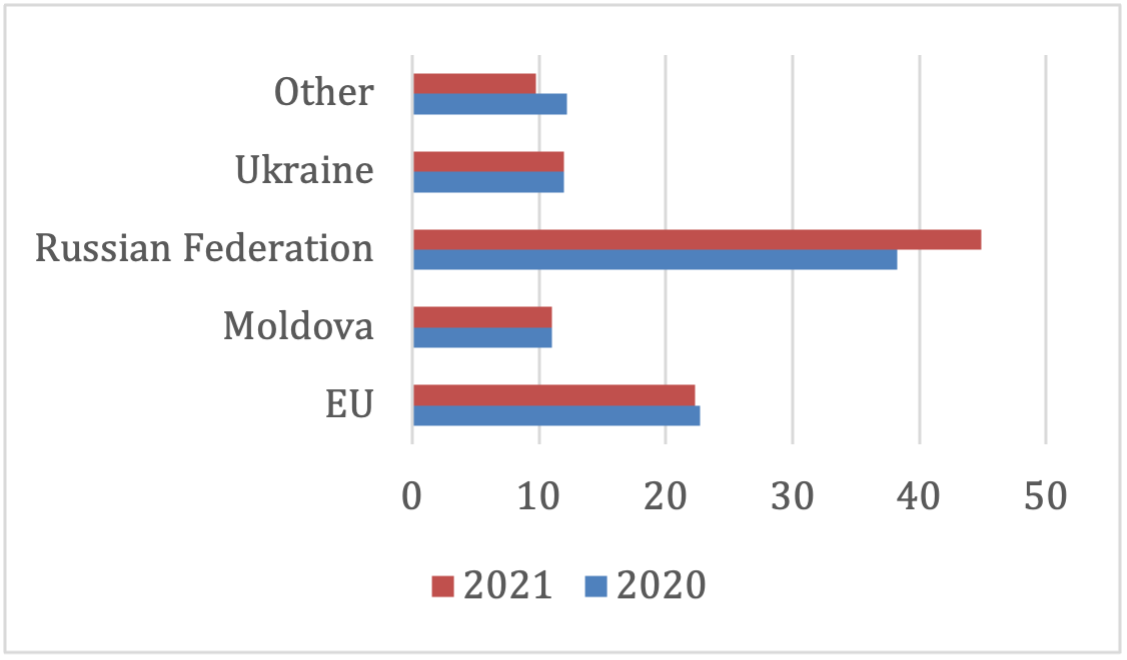

However, Transnistria remains reliant on Russia for its imports, particularly in the energy sector. In contrast to the export structure, Russia’s share in Transnistrian imports was significantly larger in 2021. About 45 percent of the imports originated from Russia in 2021, and mostly constituted of fuel and energy goods (447.0 million US dollars) and metal imports (254.3 million US dollars), quite typical for a transition economy.

Figure 4. Transnistrian imports by origin countries, in percent

Source: Data from the Pridnestrovian Republican Bank Bulletins (2024c).

Transnistria’s Energy Dependence on Russia

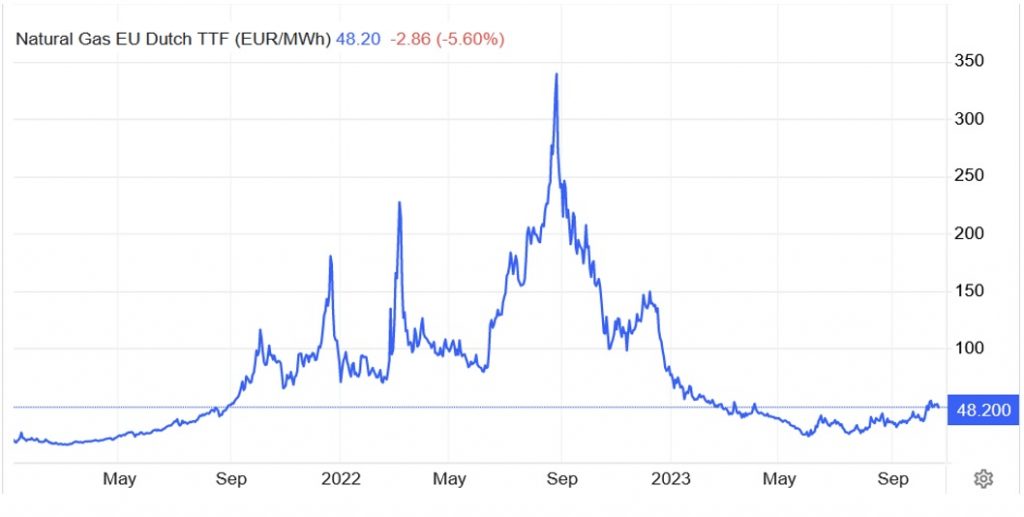

The biggest challenge for Transnistria, as well as for Moldova, is the large fuel and energy dependence on Russia, mostly in the form of natural gas.

For many years, gas has been supplied to Transnistria effectively for free, often in the form of a so-called “gas subsidy” (Roșa, 2021). This gas flows through Transnistria to Moldova, effectively accumulating a gas debt. Typically, Gazprom supplies gas to Moldovagaz, which in turn distributes gas to Moldovan consumers and to Tiraspol-Transgaz in Transnistria. Tiraspol-Transgaz then resell the gas at subsidized tariffs to local Transnistrian households and businesses. This included providing gas to the Moldovan State Regional Power Station, also known as MGRES – the largest power plant in Moldova. MGRES, in turn, exports electricity, further highlighting the interconnectedness of energy distribution between the Transnistrian region and the rest of Moldova.

Figure 5. Export/import of fuel and energy products from/to Transnistria, in million USD

Source: Data from the Pridnestrovian Republican Bank Bulletins (2024c). Note: Data for 2017 and 2018 unavailable.

The revenue generated from energy exports to Moldova has been deposited into a so-called special gas account and subsequently channeled directly into the Transnistrian budget in the form of loans from Tiraspol-Transgaz. In this way the Transnistrian government has covered more than 30 percent of their total budgetary expenditures over the last ten-year period. This further points to Transnistria’s’ fiscal inefficiencies and highlights its precarious dependency on gas from the Russian Federation.

In the last few years there have however been repeated disruptions in the gas supply and continuous disputes about prices and how much Moldovagaz owes Gazprom. De jure Tiraspol-Transgaz operates as a subsidiary of Moldovagaz, but de facto its assets were effectively nationalized by the separatist authorities in Transnistria (Tofilat and Parlicov, 2020). These unclarities has led to multiple conflicts over who owes the built-up gas debt. Given the ownership structure the debt is often seen as “Moldovan debt to Russia” (see e.g., Miller, 2023), albeit created by Transnistrian authorities. According to Gazprom, the outstanding amount owed by Moldovagaz to Gazprom stood at approximately 8 billion USD at the end of 2019 (Gazprom, 2024). This corresponds to about 7 times of Transnistria’s GDP. The Moldavian assessment of the debt is about two orders of magnitude lower (Gotev, 2023).

The disagreement on the debt amount was the official reason for the gas supply to be drastically reduced in October 2022. From December 2022 to March 2023, Russia’s Gazprom supplied gas only to Transnistria and it was not until March 2023 that supplies to the rest of Moldova were resumed. Since then, there have been shifts back and forth with Moldova mainly buying gas from Moldovan state-owned Energocom, which imports gas from suppliers other than Gazprom (Całus, 2023; Tanas, 2023). Understanding all turns and events is at times challenging due to lack of transparency in dealings.

Currently, despite Gazprom’s debt claims, the entirety of Transnistria’s gas is still being provided by Russia. While this is a relatively “cheap” investment from the Russian perspective, its impact on Moldova is large, as highlighted by Tofilat and Parlicov (2020) “the bottomline costs for Russia with maintaining Transnistria as its main instrument of influence in Moldova was at most USD 1 billion—not too expensive for twenty-seven years of influence in a European country of 3 million people”.

Corruption in Transnistria – Who is the Real “Sheriff”?

Another obstacle hindering a resolution of the Transnistrian conflict is the near complete monopoly of political and economic power held by Transnistria’s former President Igor Smirnov (1991-2011), through his strong ties to the Sheriff corporation. The corporation, established in 1993 by two former members of Transnistria’s “special services” (Ilya Kazmaly and Victor Gushan), was enabled by Transnistria’s former president, Igor Smirnov. For instance, the Sheriff company was exempt from paying customs duties and was permitted to monopolize trade, oil, and telecommunications in Transnistria. In return, the company supported Smirnov’s party during his presidency. For more on the conflict between Transnistria’s power clans and their relationships with Russia, see Hedenskog and Roine (2009) and Wesolowsky (2021).

The Sheriff company encompasses supermarkets, gas stations, construction firms, hotels, a mobile phone network, bakeries, a distillery, and a mini media empire comprising radio and TV stations. Presently, the company is reported to exert control over approximately 60 percent of the region’s economy (Wesolowsky, 2021).

A straightforward illustration of Sheriff’s political influence is the establishment of the Sheriff football team. For the team, Victor Gushan constructed the Sheriff sports complex, the largest football stadium in Moldova, accommodating

12 746 spectators. This investment in sports infrastructure is notable, especially considering that the total population of Transnistria is only approximately 350 000, and that the region is fairy poor. A similar example concerns the allocation of a land plot of 6.4 hectares to the company “to expand the construction of sports complex for long-term use under a simplified privatization procedure” signed directly by the former president.

While these details may seem peripheral to broader problems, they illustrate how some vested interests in the Transnistrian region may not be keen to change towards a society based on the rule-of-law, increased transparency and a market-oriented economy.

Moldova’s Options for Resolving the Transnistrian Conflict in EU Integration

As Moldova grapples with both the consequences of the ongoing conflict in Ukraine and the prolonged “frozen” conflict with Transnistria, its economy remains vulnerable. With the recent attainment of EU candidate status, it’s essential for the Moldovan government to map out ways to solve the conflict despite strong interest from powerful political and economic groups in preserving the status quo.

While the perspectives of resolving the Transnistrian conflict obviously hinge on Russian troops withdrawing from the region, Moldova would also need to address a wide range of economic issues. The Transnistrian economy faces numerous critical structural challenges including a persistent negative foreign trade balance, an unsustainable banking system, and pervasive corruption. Notably, the dominant oligarchic entity, the Sheriff company, exercises monopolistic political and economic influence, striving to preserve the status quo for Transnistria. The obvious unviability of the local currency due to its artificial nature and a complete dependency on Russia’s banking system are additional challenges to be solved for Moldova to be able to integrate Transnistria properly into its economy. Therefore, introducing additional measures such as restricting access to remittances in Transnistria, and imposing personal sanctions on elite groups could help Moldova in establishing economic control over the region.

Furthermore, while the Transnistrian region de-facto has strong economic ties with the Moldovan and European markets in terms of exports, its heavy reliance on Russian gas imports remains a significant vulnerability.

When integrating Transnistria and severing its ties with Russia, Moldova would also need to resolve the issues arising from its reliance on the electricity produced at MGRES using subsidized Russian gas. Natural gas bought at market prices would make Moldovan electricity highly costly, presenting financial challenges to Moldova, and effectively destroying the competitive advantage and important source of revenue in the Transnistrian region. Moreover, alternative electricity routes to Moldova are yet to be completed (with an estimated cost of approximately 27 million EUR).

These and other issues need to be dealt with for a successful Moldovan transition into the EU. Although these challenges are highly important from a Moldovan point of view, and even more so from a Transnistrian perspective, it should be emphasized that these issues are, in economic terms, relatively small for the EU. Given that the EU has opened the way for Moldovan accession, it should be ready to step up financially to help Moldova solve these issues and stay on the membership path.

References

- Całus, K. (2023, June 15). Moldova: diversifying supplies and curbing Gazprom’s influence. OSW Centre for Eastern Studies. https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/analyses/2023-06-15/moldova-diversifying-supplies-and-curbing-gazproms-influence

- Constitute. (2024). Constitution of Moldova (Republic of) 1994 (revision 2016). Https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Moldova_2016

- European Council. (2024, June 25). EU opens accession negotiations with Moldova. https://neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/news/eu-opens-accession-negotiations-moldova-2024-06-25_en

- European Parliament. (2022, June 23). Grant EU candidate status to Ukraine and Moldova without delay. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20220616IPR33216/grant-eu-candidate-status-to-ukraine-and-moldova-without-delay-meps-demand

- European Union Border Assistance Mission to Republic of Moldova and Ukraine (EUBAM). (2017). ENPI 2008 C2008 3821 RAP East EUBAM 6. https://neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2017-03/enpi_2008_c2008_3821_rap_east_eubam_6.pdf

- Gazprom. (2024). Gazprom financial report for Q4/2019. https://www.gazprom.ru/f/posts/77/885487/gazprom-ifrs-2019-12m-ru.pdf

- Gotev, G. (2023, September 7). Moldova puts its debt to Gazprom at $8.6 million, Russia disagrees. EURACTIV. https://www.euractiv.com/section/energy-environment/news/moldova-puts-its-debt-to-gazprom-at-8-6-million-russia-disagrees/

- Government of Republic of Moldova. (1992, July 21). Agreement on Principles of Peaceful Settlement of the Armed Conflict in the Transnistrian Region of Moldovan Republic. https://gov.md/sites/default/files/1992-07-21-ru-moscow-agr_on_principles_of_peaceful_settlem.pdf

- Hedenskog, J., & Roine, J. (2009). Transnistrien. En Ekonomisk och Säkerhetspolitisk Analys. Utrikesdepartementet/Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Sweden. Stockholm, 40 p.

- Leontiev, L. (2022, March 25). Big, But Distant Dreams. Political and Legal Implications of Moldova’s Quest for EU Membership. The Review of Democracy. https://revdem.ceu.edu/2022/03/25/big-but-distant-dreams-political-and-legal-implications-of-moldovas-quest-for-eu-membership/

- Miller, M. (2023, September 7). Independent Audit of Gazprom’s Debt Claims Against Moldovagaz. U.S. Embassy in Moldova. https://md.usembassy.gov/independent-audit-of-gazproms-debt-claims-against-moldovagaz/

- Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE). (2022, March 15). Consequences of the Russian Federation’s aggression against Ukraine. https://pace.coe.int/en/files/29885/html

- Pridnestrovian Republican Bank. (2024a). Main macroeconomic parameters of PMR. https://www.cbpmr.net/content.php?Id=13&lang=ru

- Pridnestrovian Republican Bank (2024b). Remittances. https://www.cbpmr.net/content.php?Id=110&lang=ru

- Pridnestrovian Republican Bank (2024c). Pridnestrovian Republican Bank Bulletins. https://www.cbpmr.net/content.php?Id=28&lang=ru

- Racz, A. (2016, April 8). The Frozen Conflicts of the EU’s Eastern Neighbourhood and Their Impact on the Respect of Human Rights. European Parliament Think Tank. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EXPO_STU(2016)578001

- Roșa, V. (2021, October 18). The Transnistrian Conflict: 30 Years Searching for a Settlement. SCEEUS Reports on Human Rights and Security in Eastern Europe No.4. https://sceeus.se/publikationer/the-transnistrian-conflict-30-years-searching-for-a-settlement/

- Statista. (2024). Moldova: Distribution of gross domestic product (GDP) across economic sectors from 2012 to 2022. https://www.statista.com/statistics/513314/moldova-gdp-distribution-across-economic-sectors/

- Tanas, A. (2023, March 21). Moldova resumes gas purchases from Russia’s Gazprom -Moldovagaz head. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/moldova-resumes-gas-purchases-russias-gazprom-moldovagaz-head-2023-03-21/

- Tofilat, S., & Parlicov, V. (2020, August 14). Russian Gas and the Financing of Separatism in Moldova. The Kremlin’s Influence Quarterly #2. https://www.4freerussia.org/russian-gas-and-the-financing-of-separatism-in-moldova/

- Wesolowsky, T. (2021, October 18). The Shadow Business Empire Behind the Meteoric Rise of Sheriff Tiraspol. RadioFreeEurope. https://www.rferl.org/a/moldova-sheriff-tiraspol-murky-business/31516518.html

- World Bank. (2024a). Data. Moldova. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD?Locations=MD

- World Bank. (2024b). Personal remittances, received (% of GDP) – Moldova. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.TRF.PWKR.DT.GD.ZS?Locations=MD

- World Bank. (2024c). Moldova Overview. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/moldova/overview

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in policy briefs and other publications are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect those of the FREE Network and its research institutes.

Gender Gap in Life Expectancy and Its Socio-Economic Implications

Today women live longer than men virtually in every country of the world. Although scientists still struggle to fully explain this disparity, the most prominent sources of this gender inequality are biological and behavioral. From an evolutionary point of view, female longevity was more advantageous for offspring survival. This resulted in a higher frequency of non-fatal diseases among women and in a later onset of fatal conditions. The observed high variation in the longevity gap across countries, however, points towards an important role of social and behavioral arguments. These include higher consumption of alcohol, tobacco, and fats among men as well as a generally riskier behavior. The gender gap in life expectancy often reaches 6-12 percent of the average human lifespan and has remained stubbornly stable in many countries. Lower life expectancy among men is an important social concern on its own and has significant consequences for the well-being of their surviving partners and the economy as a whole. It is an important, yet under-discussed type of gender inequality.

Country Reports

| Belarus Country Report | FROGEE POLICY BRIEF |

| Georgia Country Report | FROGEE POLICY BRIEF |

| Latvia Country Report | FROGEE POLICY BRIEF |

| Poland Country Report | FROGEE POLICY BRIEF |

Gender Gap in Life Expectancy and Its Socio-Economic Implications

Today, women on average live longer than men across the globe. Despite the universality of this basic qualitative fact, the gender gap in life expectancy (GGLE) varies a lot across countries (as well as over time) and scientists have only a limited understanding of the causes of this variation (Rochelle et al., 2015). Regardless of the reasons for this discrepancy, it has sizable economic and financial implications. Abnormal male mortality makes a dent in the labour force in nations where GGLE happens to be the highest, while at the same time, large GGLE might contribute to a divergence in male and female discount factors with implications for employment and pension savings. Large discrepancies in life expectancy translate into a higher incidence of widowhood and a longer time in which women live as widows. The gender gap in life expectancy is one of the less frequently discussed dimensions of gender inequality, and while it clearly has negative implications for men, lower male longevity has also substantial negative consequences for women and society as a whole.

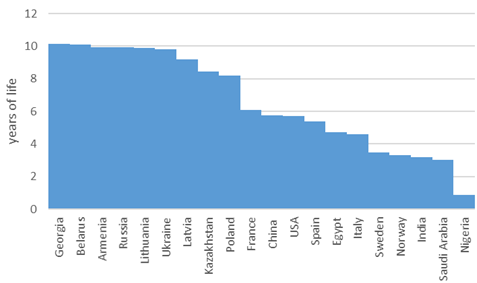

Figure A. Gender gap in life expectancy across selected countries

Source: World Bank.

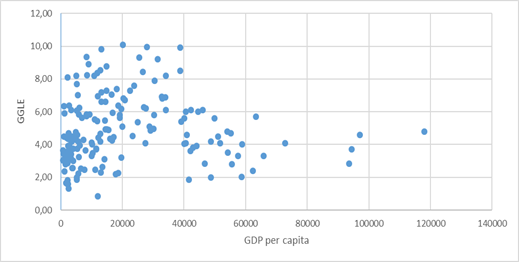

The earliest available reliable data on the relative longevity of men and women shows that the gender gap in life expectancy is not a new phenomenon. In the middle of the 19th century, women in Scandinavian countries outlived men by 3-5 years (Rochelle et al., 2015), and Bavarian nuns enjoyed an additional 1.1 years of life, relative to the monks (Luy, 2003). At the beginning of the 20th century, relative higher female longevity became universal as women started to live longer than men in almost every country (Barford et al., 2006). GGLE appears to be a complex phenomenon with no single factor able to fully explain it. Scientists from various fields such as anthropology, evolutionary biology, genetics, medical science, and economics have made numerous attempts to study the mechanisms behind this gender disparity. Their discoveries typically fall into one of two groups: biological and behavioural. Noteworthy, GGLE seems to be fairly unrelated to the basic economic fundamentals such as GDP per capita which in turn has a strong association with the level of healthcare, overall life expectancy, and human development index (Rochelle et al., 2015). Figure B presents the (lack of) association between GDP per capita and GGLE in a cross-section of countries. The data shows large heterogeneity, especially at low-income levels, and virtually no association from middle-level GDP per capita onwards.

Figure B. Association between gender gap in life expectancy and GDP per capita

Source: World Bank.

Biological Factors

The main intuition behind female superior longevity provided by evolutionary biologists is based on the idea that the offspring’s survival rates disproportionally benefited from the presence of their mothers and grandmothers. The female hormone estrogen is known to lower the risks of cardiovascular disease. Women also have a better immune system which helps them avoid a number of life-threatening diseases, while also making them more likely to suffer from (non-fatal) autoimmune diseases (Schünemann et al., 2017). The basic genetic advantage of females comes from the mere fact of them having two X chromosomes and thus avoiding a number of diseases stemming from Y chromosome defects (Holden, 1987; Austad, 2006; Oksuzyan et al., 2008).

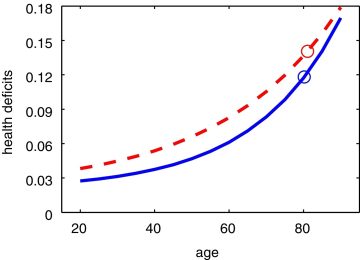

Despite a number of biological factors contributing to female longevity, it is well known that, on average, women have poorer health than men at the same age. This counterintuitive phenomenon is called the morbidity-mortality paradox (Kulminski et al., 2008). Figure C shows the estimated cumulative health deficits for both genders and their average life expectancies in the Canadian population, based on a study by Schünemann et al. (2017). It shows that at any age, women tend to have poorer health yet lower mortality rates than men. This paradox can be explained by two factors: women tend to suffer more from non-fatal diseases, and the onset of fatal diseases occurs later in life for women compared to men.

Figure C. Health deficits and life expectancy for Canadian men and women

Source: Schünemann et al. (2017). Note: Men: solid line; Women: dashed line; Circles: life expectancy at age 20.

Behavioural Factors

Given the large variation in GGLE, biological factors clearly cannot be the only driving force. Worldwide, men are three times more likely to die from road traffic injuries and two times more likely to drown than women (WHO, 2002). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the average ratio of male-to-female completed suicides among the 183 surveyed countries is 3.78 (WHO, 2024). Schünemann et al. (2017) find that differences in behaviour can explain 3.2 out of 4.6 years of GGLE observed on average in developed countries. Statistics clearly show that men engage in unhealthy behaviours such as smoking and alcohol consumption much more often than women (Rochelle et al., 2015). Men are also more likely to be obese. Alcohol consumption plays a special role among behavioural contributors to the GGLE. A study based on data from 30 European countries found that alcohol consumption accounted for 10 to 20 percent of GGLE in Western Europe and for 20 to 30 percent in Eastern Europe (McCartney et al., 2011). Another group of authors has focused their research on Central and Eastern European countries between 1965 and 2012. They have estimated that throughout that time period between 15 and 19 percent of the GGLE can be attributed to alcohol (Trias-Llimós & Janssen, 2018). On the other hand, tobacco is estimated to be responsible for up to 30 percent and 20 percent of the gender gap in mortality in Eastern Europe and the rest of Europe, respectively (McCartney et al., 2011).

Another factor potentially decreasing male longevity is participation in risk-taking activities stemming from extreme events such as wars and military activities, high-risk jobs, and seemingly unnecessary health-hazardous actions. However, to the best of our knowledge, there is no rigorous research quantifying the contribution of these factors to the reduced male longevity. It is also plausible that the relative importance of these factors varies substantially by country and historical period.

Gender inequality and social gender norms also negatively affect men. Although women suffer from depression more frequently than men (Albert, 2015; Kuehner, 2017), it is men who commit most suicides. One study finds that men with lower masculinity (measured with a range of questions on social norms and gender role orientation) are less likely to suffer from coronary heart disease (Hunt et al., 2007). Finally, evidence shows that men are less likely to utilize medical care when facing the same health conditions as women and that they are also less likely to conduct regular medical check-ups (Trias-Llimós & Janssen, 2018).

It is possible to hypothesize that behavioural factors of premature male deaths may also be seen as biological ones with, for example, risky behaviour being somehow coded in male DNA. But this hypothesis may have only very limited truth to it as we observe how male longevity and GGLE vary between countries and even within countries over relatively short periods of time.

Economic Implications

Premature male mortality decreases the total labour force of one of the world leaders in GGLE, Belarus, by at least 4 percent (author’s own calculation, based on WHO data). Similar numbers for other developed nations range from 1 to 3 percent. Premature mortality, on average, costs European countries 1.2 percent of GDP, with 70 percent of these losses attributable to male excess mortality. If male premature mortality could be avoided, Sweden would gain 0.3 percent of GDP, Poland would gain 1.7 percent of GDP, while Latvia and Lithuania – countries with the highest GGLE in the EU – would each gain around 2.3 percent of GDP (Łyszczarz, 2019). Large disparities in the expected longevity also mean that women should anticipate longer post-retirement lives. Combined with the gender employment and pay gap, this implies that either women need to devote a larger percentage of their earnings to retirement savings or retirement systems need to include provisions to secure material support for surviving spouses. Since in most of the retirement systems the value of pensions is calculated using average, not gender-specific, life expectancy, the ensuing differences may result in a perception that men are not getting their fair share from accumulated contributions.

Policy Recommendations

To successfully limit the extent of the GGLE and to effectively address its consequences, more research is needed in the area of differential gender mortality. In the medical research dimension, it is noteworthy that, historically, women have been under-represented in recruitment into clinical trials, reporting of gender-disaggregated data in research has been low, and a larger amount of research funding has been allocated to “male diseases” (Holdcroft, 2007; Mirin, 2021). At the same time, the missing link research-wise is the peculiar discrepancy between a likely better understanding of male body and health and the poorer utilization of this knowledge.

The existing literature suggests several possible interventions that may substantially reduce premature male mortality. Among the top preventable behavioural factors are smoking and excessive alcohol consumption. Many studies point out substantial country differences in the contribution of these two factors to GGLE (McCartney, 2011), which might indicate that gender differences in alcohol and nicotine abuse may be amplified by the prevailing gender roles in a given society (Wilsnack et al., 2000). Since the other key factors impairing male longevity are stress and risky behaviour, it seems that a broader societal change away from the traditional gender norms is needed. As country differences in GGLE suggest, higher male mortality is mainly driven by behaviours often influenced by societies and policies. This gives hope that higher male mortality could be reduced as we move towards greater gender equality, and give more support to risk-reducing policies.

While the fundamental biological differences contributing to the GGLE cannot be changed, special attention should be devoted to improving healthcare utilization among men and to increasingly including the effects of sex and gender in medical research on health and disease (Holdcoft, 2007; Mirin, 2021; McGregor et al., 2016, Regitz-Zagrosek & Seeland, 2012).

References

- Albert, P. R. (2015). “Why is depression more prevalent in women?“. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience, 40(4), 219.

- Austad, S. N. (2006). “Why women live longer than men: sex differences in longevity“. Gender Medicine, 3(2), 79-92.

- Barford, A., Dorling, D., Smith, G. D., & Shaw, M. (2006). “Life expectancy: women now on top everywhere“. BMJ, 332, 808. doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7545.808

- Holden, C. (1987). “Why do women live longer than men?“. Science, 238(4824), 158-160.

- Hunt, K., Lewars, H., Emslie, C., & Batty, G. D. (2007). “Decreased risk of death from coronary heart disease amongst men with higher ‘femininity’ scores: A general population cohort study“. International Journal of Epidemiology, 36, 612-620.

- Kulminski, A. M., Culminskaya, I. V., Ukraintseva, S. V., Arbeev, K. G., Land, K. C., & Yashin, A. I. (2008). “Sex-specific health deterioration and mortality: The morbidity-mortality paradox over age and time“. Experimental Gerontology, 43(12), 1052-1057.

- Luy, M. (2003). “Causes of Male Excess Mortality: Insights from Cloistered Populations“. Population and Development Review, 29(4), 647-676.

- McCartney, G., Mahmood, L., Leyland, A. H., Batty, G. D., & Hunt, K. (2011). “Contribution of smoking-related and alcohol-related deaths to the gender gap in mortality: Evidence from 30 European countries“. Tobacco Control, 20, 166-168.

- McGregor, A. J., Hasnain, M., Sandberg, K., Morrison, M. F., Berlin, M., & Trott, J. (2016). “How to study the impact of sex and gender in medical research: A review of resources“. Biology of Sex Differences, 7, 61-72.

- Mirin, A. A. (2021). “Gender disparity in the funding of diseases by the US National Institutes of Health“. Journal of Women’s Health, 30(7), 956-963.

- Oksuzyan, A., Juel, K., Vaupel, J. W., & Christensen, K. (2008). “Men: good health and high mortality. Sex differences in health and aging“. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 20(2), 91-102.

- Regitz-Zagrosek, V., & Seeland, U. (2012). “Sex and gender differences in clinical medicine“. Sex and Gender Differences in Pharmacology, 3-22.

- Rochelle, T. R., Yeung, D. K. Y., Harris Bond, M., & Li, L. M. W. (2015). “Predictors of the gender gap in life expectancy across 54 nations“. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 20(2), 129-138. doi:10.1080/13548506.2014.936884

- Schünemann, J., Strulik, H., & Trimborn, T. (2017). “The gender gap in mortality: How much is explained by behavior?“. Journal of Health Economics, 54, 79-90.

- Trias-Llimós, S., & Janssen, F. (2018). “Alcohol and gender gaps in life expectancy in eight Central and Eastern European countries“. European Journal of Public Health, 28(4), 687-692.

- WHO. (2002). “Gender and road traffic injuries“. World Health Organization.

- WHO. (2024). “Global health estimates: Leading causes of death“. World Health Organization.

- Łyszczarz, B. (2019). “Production losses associated with premature mortality in 28 European Union countries“. Journal of Global Health.

About FROGEE Policy Briefs

FROGEE Policy Briefs is a special series aimed at providing overviews and the popularization of economic research related to gender equality issues. Debates around policies related to gender equality are often highly politicized. We believe that using arguments derived from the most up to date research-based knowledge would help us build a more fruitful discussion of policy proposals and in the end achieve better outcomes.

The aim of the briefs is to improve the understanding of research-based arguments and their implications, by covering the key theories and the most important findings in areas of special interest to the current debate. The briefs start with short general overviews of a given theme, which are followed by a presentation of country-specific contexts, specific policy challenges, implemented reforms and a discussion of other policy options.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in policy briefs and other publications are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect those of the FREE Network and its research institutes.

Navigating Market Exits: Companies’ Responses to the Russian Invasion of Ukraine

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022 led to widespread international condemnation. As governments imposed sanctions on Russian businesses and individuals tied to the war, international companies doing business in Russia came under increasing pressure to withdraw from Russia voluntarily. In the first part of this policy brief, we show what kind of companies decided to leave the Russian market using data collected by the LeaveRussia project. In the second part, we focus on prominent Swedish businesses which announced a withdrawal from Russia, but whose products were later found available in the country by investigative journalists from Dagens Nyheter (DN). We collect the stock prices for these companies when available and show how investors respond to these news.

Business Withdrawal from Russia

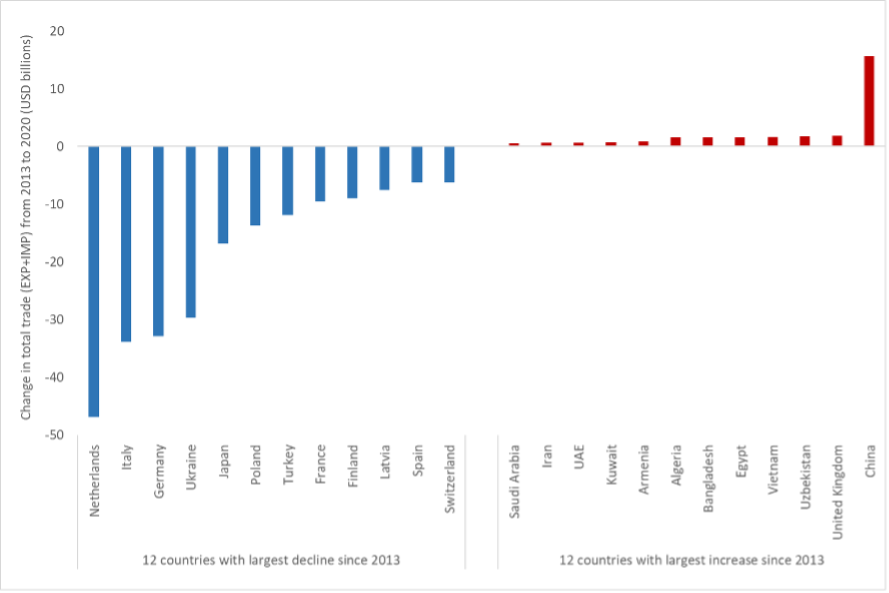

The global economy is highly interconnected, and Russia forms an important part. Prior to the invasion, Russia ranked 13th in the world in terms of global goods exports value and 22nd in terms of imports (Schwarzenberg, 2023). In the months following the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russia’s imports dropped sharply (about 50 percent according to Sonnenfeld et al., 2022). Before February 24th, Russia’s main trading partners were China, the European Union (in particular, Germany and the Netherlands) and Belarus (as illustrated in Figure 1). While there is some evidence of Russia shifting away from Western countries and towards China following the annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the resulting sanctions, Western democracies still made up about 60 percent of Russia’s trade in 2020 (Schwarzenberg, 2023). In the same year, Sweden’s exports to Russia accounted for 1.4 percent of Sweden’s total goods exports, of which 59 percent were in the machinery, transportation and telecommunications sectors. 1.3 percent of Swedish imports were from Russia (Stockholms Handelskammare, 2022).

Figure 1. Changes in trade with Russia, 2013-2020.

Source: IMF Direction of Trade Statistics, data until 2020. From Lehne (2022).

In response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2024, Western governments imposed strict trade and financial sanctions on Russian businesses and individuals involved in the war (see S&P Global, 2024). These sanctions are designed to hamper Russia’s war effort by reducing its ability to fight and finance the war. The sanctions make it illegal for, e.g., European companies to sell certain products to Russia as well as to import select Russian goods (Council of the European Union, 2024). Even though sanctions do not cover all trade with Russia, many foreign businesses have been pressured to pull out of Russia in an act of solidarity. The decision by these businesses to leave is voluntary and could reflect their concerns over possible consumer backlash. It is not uncommon for consumers to put pressure on businesses in times of geopolitical conflict. For instance, Pandya and Venkatesan (2016) find that U.S. consumers were less likely to buy French-sounding products when the relationship between both countries deteriorated.

The LeaveRussia Project

The LeaveRussia project, from the Kyiv School of Economics Institute (KSE Institute), systematically tracks foreign companies’ responses to the Russian invasion. The database covers a selection of companies that have either made statements regarding their operations in Russia, and/or are a large global player (“major companies and world-famous brands”), and/or have been mentioned in relation to leaving/waiting/withdrawing from Russia in major media outlets such as Reuters, Bloomberg, Financial times etc. (LeaveRussia, 2024). As of April 5th, 2024, the list contains 3342 firms, the companies’ decision to leave, exit or remain in the Russian market, the date of their announced action, and company details such as revenue, industry etc. The following chart uses publicly available data from the LeaveRussia project to illustrate patterns in business withdrawals from Russia following the invasion of Ukraine.

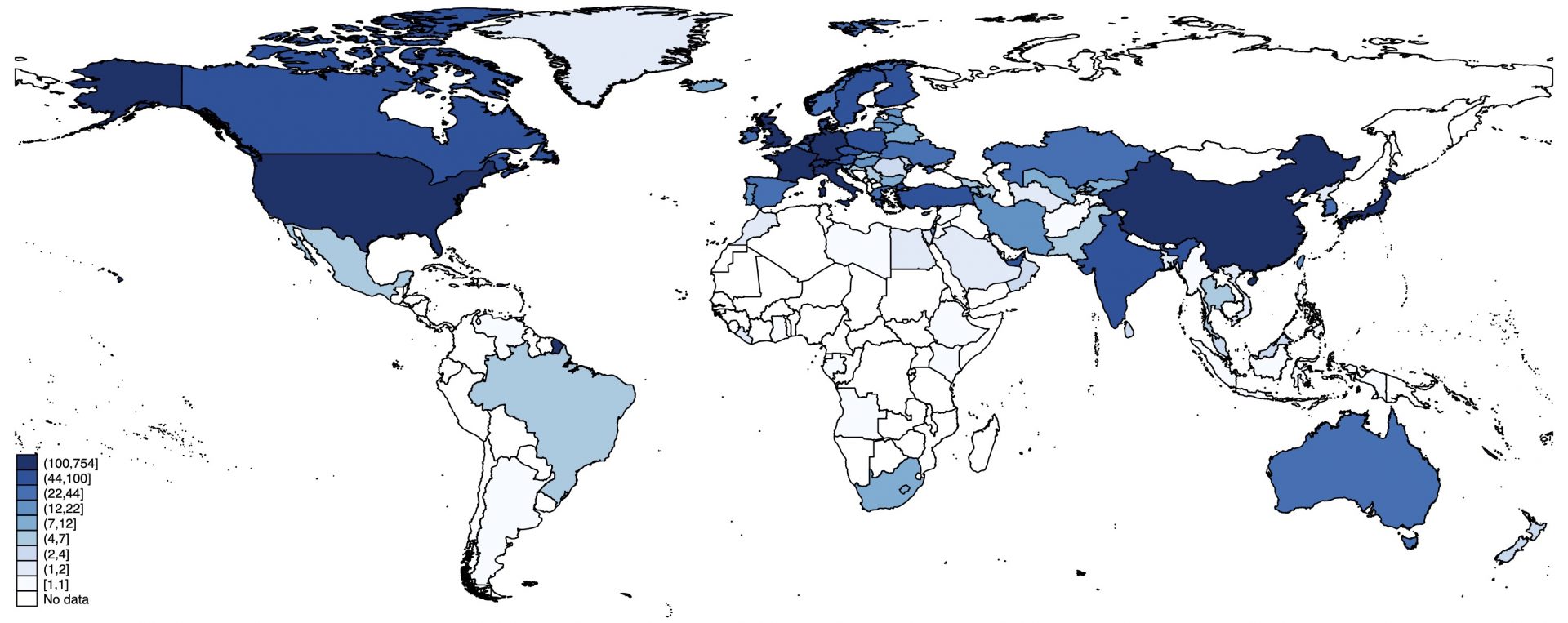

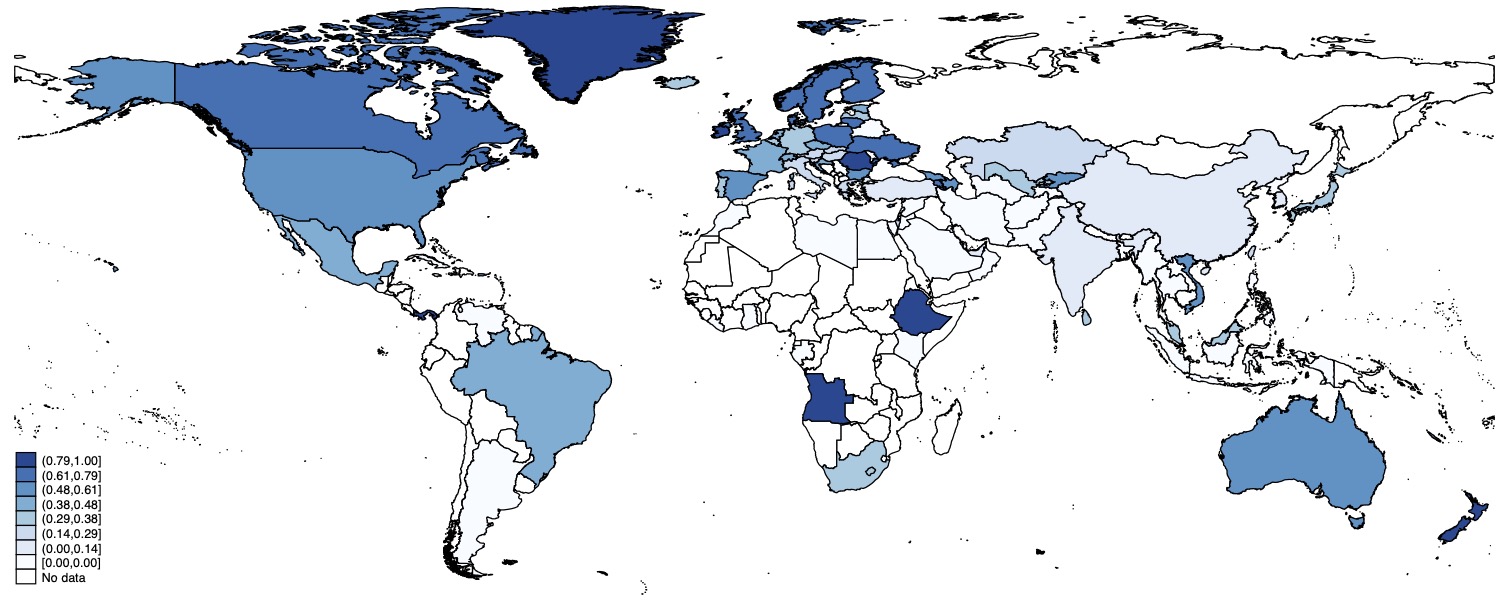

Figure 2a shows the number of foreign companies in Russia in the LeaveRussia dataset by their country of headquarters. Figure 2b shows the share of these companies that have announced a withdrawal from Russia by April 2024, by their country of headquarters.

Figure 2a. Total number of companies by country.

Figure 2b. Share of withdrawals, by country.

Source: Authors’ compilation based on data from the LeaveRussia project and global administrative zone boundaries from Runfola et al. (2020).

Some countries (e.g. Canada, the US and the UK) that had a large presence in Russia prior to the war have also seen a large number of withdrawals following the invasion. Other European countries, however, have seen only a modest share of withdrawals (for instance, Italy, Austria, the Netherlands and Slovakia). Companies headquartered in countries that have not imposed any sanctions on Russia following the invasion, such as Belarus, China, India, Iran etc., show no signs of withdrawing from the Russian market. In fact, the share of companies considered by the KSE to be “digging in” (i.e., companies that either declared they’d remain in Russia or who did not announce a withdrawal or downscaling as of 31st of March 2024) is 75 percent for more than 25 countries, including not only the aforementioned, but also countries such as Argentina, Moldova, Serbia and Turkey.

Withdrawal Determinants

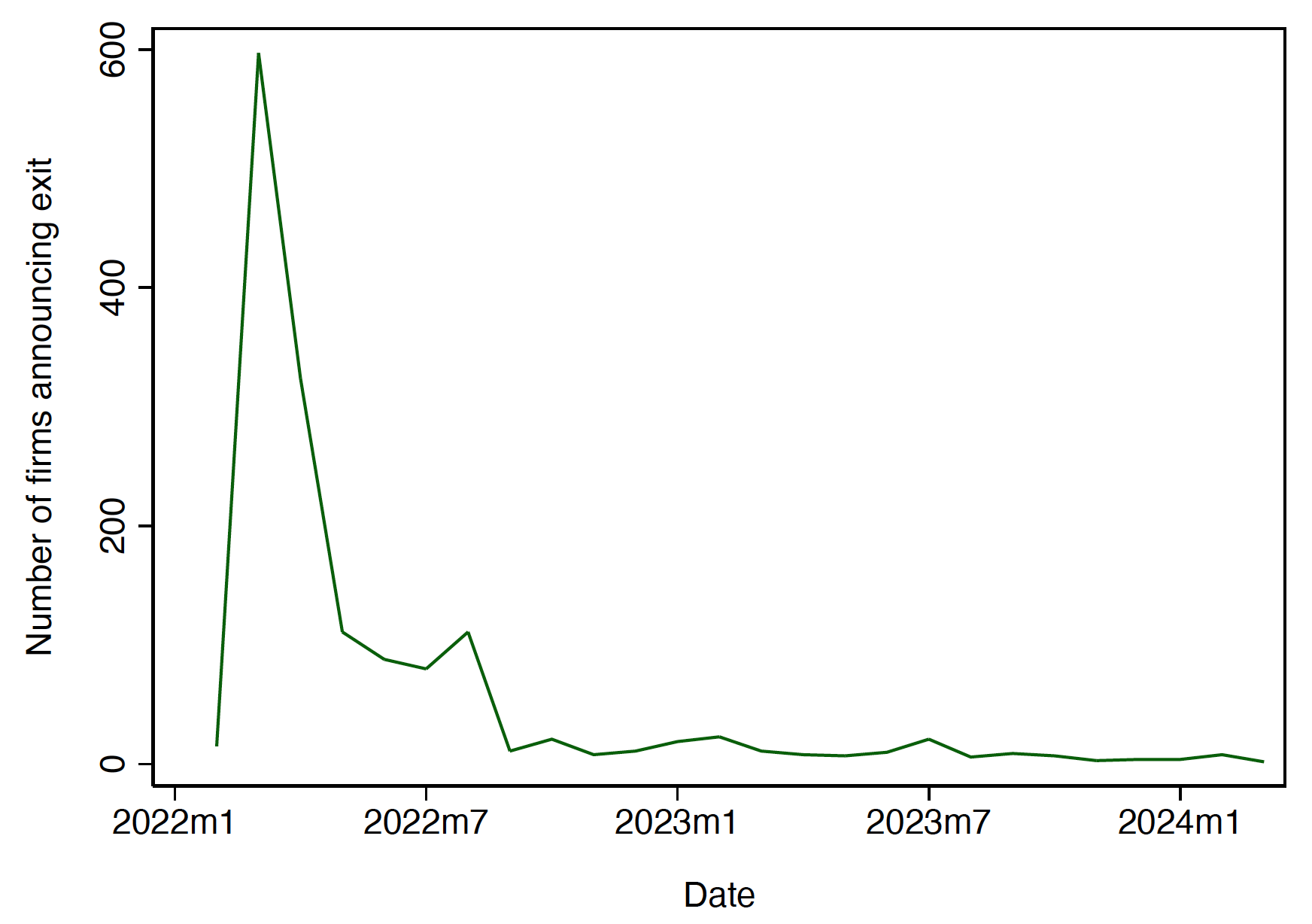

The decision for companies to exit the market may range from consumer pressure to act in solidarity with Ukraine, to companies’ perceived risk from operating on the Russian market (Kiesel and Kolaric, 2023). Out of the 3342 companies in the LeaveRussia project’s database, about 42 percent have, as of April 5th, 2024, exited or stated an intention to exit the Russian market. This number increases only slightly to 49 percent when considering only companies headquartered in democratic (an Economist Intelligence Unit Democracy Index score of 7 or higher) countries within the EU. Figure 3 shows the number of companies that announced their exit from the Russian market, by month. A clear majority of companies announce their withdrawal in the first 6 months following the invasion.

Figure 3. Number of foreign companies announcing an exit from the Russian market, 2022-2024.

Source: Authors’ compilation based on data from the LeaveRussia project.

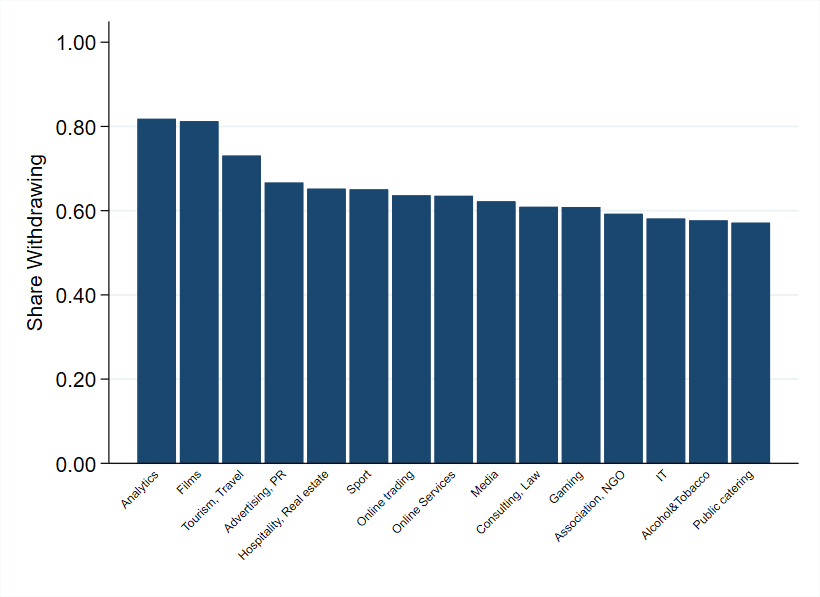

Similarly to the location of companies’ headquarters, the decision to exit the Russian market varies by industry. Figure 4 a depicts the top 15 industries with the highest share of announced withdrawals from the Russian market among industries with at least 10 companies. Most companies with high levels of withdrawals are found in consumer-sensitive industries such as the entertainment sector, tourism and hospitality, advertising etc.

Figure 4a. Top 15 industries in terms of withdrawal shares.

Figure 4b. Bottom 15 industries in terms of withdrawal shares.

Source: Authors’ compilation based on data from the LeaveRussia project.

In contrast, Figure 4b details the industries with the lowest share of companies opting to withdraw from the Russian market. Only around 10 percent of firms in the “Defense” and “Marine Transportation” industries chose to withdraw. Two-thirds of firms within the “Energy, oil and gas” and “Metals and Mining” sectors have chosen to remain in business in Russia following the war in Ukraine.

Several sectors have been identified as crucial in supplying the Russian military with necessary components to sustain their military aggression against Ukraine, mainly electronics, communications, automotives and related categories. We find that many of these sectors are among those with the lowest share of companies withdrawing from Russia. Companies for which Russia constitute a large market share have more to lose from exiting than others. Another reason for not exiting the market relates to the current legal hurdles of corporate withdrawal from Russia (Doherty, 2023). Others may simply not have made public announcements or operate within an industry dominated by smaller companies that are not on the radar of the LeaveRussia project. Nonetheless, Bilousova et al. (2024) detail that products from companies within the sanction’s coalition continue to be found in Russian military equipment destroyed in Ukraine. This is due to insufficient due diligence by companies as well as loopholes in the sanctions regime such as re-exporting via neighboring countries, tampering with declaration forms or challenges in jurisdictional enforcement due to lengthy supply chains, among others. (Olofsgård and Smitt Meyer, 2023).

And Those Who Didn’t Leave After All

The data from the LeaveRussia project details if and when foreign businesses announce that they will leave Russia. However, products from companies that have announced a departure from the Russian market continue to be found in the country, including in military components (Bilousova, 2024). In autumn 2023, investigative journalists from the Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter exposed 14 Swedish companies whose goods were found entering Russia, in most cases contrary to the companies’ public claims (Dagens Nyheter, 2023; Tidningen Näringslivet, 2023). For this series of articles, the journalists used data from Russian customs and verified it with information from numerous Swedish companies, covering the time period up until December 2022. This entailed reviewing thousands of export records from Swedish companies either directly to Russia or via neighboring countries such as Armenia, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan. All transactions mentioned in the article series have been confirmed with the respective companies, who were also contacted by DN prior to publication (Dagens Nyheter, 2023b). DNs journalists also acted as businessmen, interacting with intermediaries in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, exposing re-routing of Swedish goods from a company stated to have cut all exports to Russia in the wake of the invasion (Dagens Nyheter, 2023d).

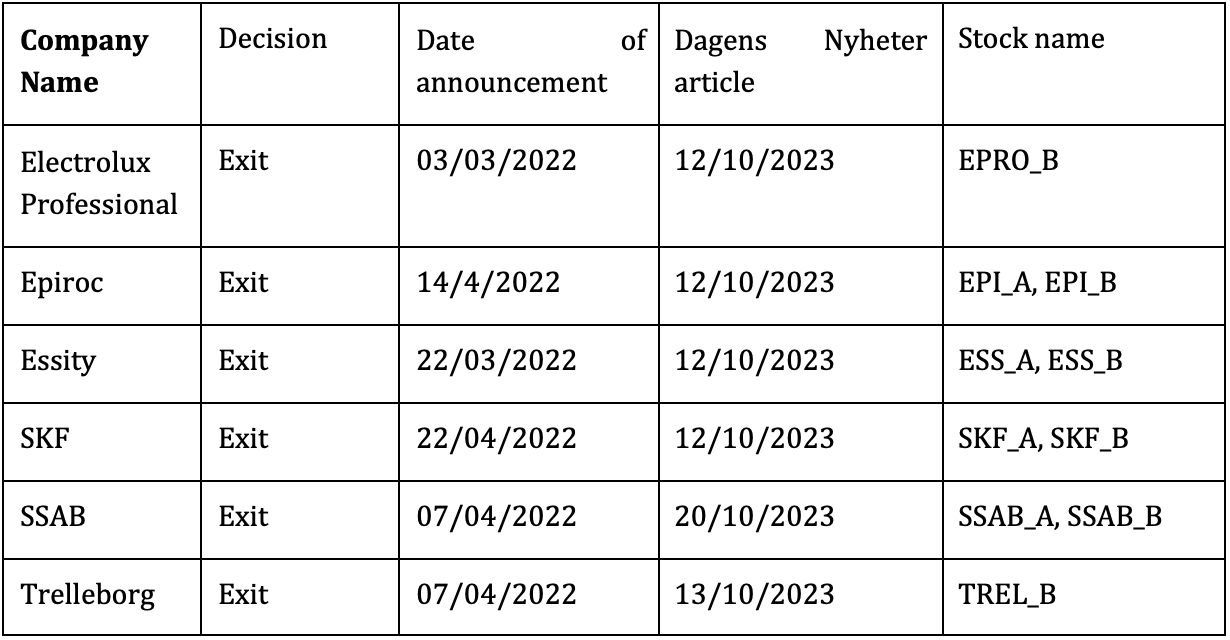

For Sweden headquartered companies exposed in DN and that are traded on the Swedish Stock Exchange, we collect their stock prices and trading volume. Our data includes information on each stock’s average price, turnover, number of trades by date from around the date of the DN publications as well as the date of each company’s prior public announcement of exiting Russia. Table 1 details the companies who were exposed of doing direct or indirect business with Russia by DN and who had announced an exit from the Russian market previously. In their article series, DN also shows that goods from the following companies entered Russia; AriVislanda, Assa Abloy, Atlas Copco, Getinge, Scania, Securitas Tetra Pak, and Väderstad. Most of the companies exposed by DN operate within industries displaying low withdrawal shares.

Table 1. Select Swedish companies’, time of exit announcement and exposure in Dagens Nyheter and stock names.

Source: The LeaveRussia project, 2023; Dagens Nyheter, 2023b, 2023c, 2023d. Note: The exit statements have been verified through companies’ press statements and/or reports when available. For Epiroc, the claim has been verified via a previous Dagens Nyheter article (Dagens Nyheter, 2023a).

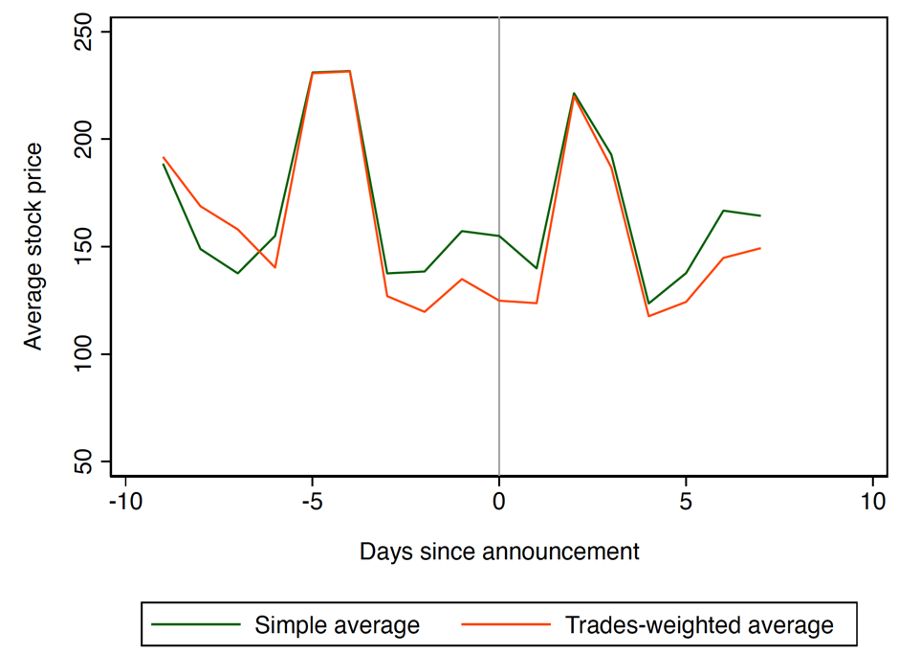

In Figure 5, we show the average stock price and trades-weighted average stock price of the Swedish companies in Table 1 around the time when the companies announced that they are leaving Russia.

Figure 5. Average stock price of companies in Table 1 around Russian exit announcements.

Source: Author’s compilation based on data from Nasdaq Nordic.

There appears to be an immediate increase in stock prices after firms announced their exit from the Russian market. Stock prices, however, reverse their gains over the next couple of days. In general, stock prices are volatile, and we also see similar-sized movements immediately before the announcement. Due to this volatility and the fact that we cannot rule out other shocks impacting these stock prices at the same time, it is difficult to attribute any movements in the stock prices to the firms’ decisions to leave Russia.

The academic evidence on investors’ reactions to firms divesting from Russia is mixed. Using a sample of less than 300 high-profile firms with operations in Russia compiled by researchers at the Yale Chief Executive Leadership Institute, Glambosky and Peterburgsky (2022) find that firms that divest within 10 days after the invasion experience negative returns, but then recover within a two-week period. Companies announcing divesting at a later stage do not experience initial stock price declines. In contrast, Kiesel and Kolaric (2023) use data from the LeaveRussia project to find positive stock price returns to firms’ announcements of leaving Russia, while there appears to be no significant investor reaction to firms’ decisions to stay in Russia.

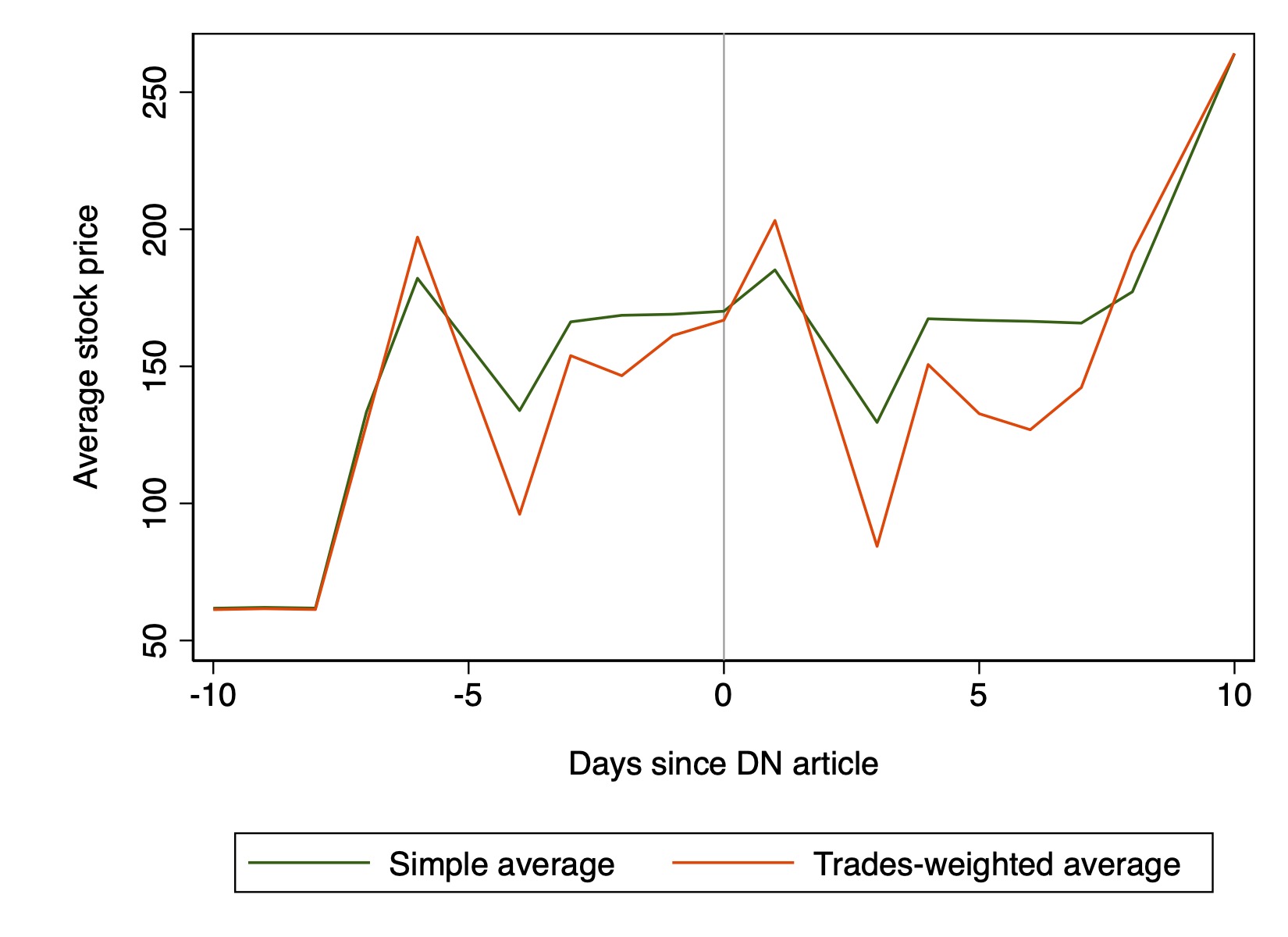

When considering the effect from DN’s publications, the picture is almost mirrored, with the simple and trades-weighted average stock prices dipping in the days following the negative media exposure before not only recovering, but actually increasing. Similar caveats apply to the interpretation of this chart. In addition, the DN publication occurred shortly after the Hamas attacks on Israel on October 7 and Israel’s subsequent war on Gaza. While conflict and uncertainty typically dampen the stock market, the events in the Middle East initially caused little reaction on the stock market (Sharma, 2023).

Figure 6. Average stock price for companies listed in Table 1 around the time of DN exposure.

Source: Author’s compilation based on data from Nasdaq Nordic.

Discussion

As discussed in Becker et al. (2024), creating incentives and ensuring companies follow suit with the current sanctions’ regime should be a priority if we want to end Russia’s war on Ukraine and undermine its wider geopolitical ambitions. Nevertheless, Bilousova et al. (2024), and Olofsgård and Smitt Meyer (2023), highlight that there is ample evidence of sanctions evasions, including for products that are directly contributing to Russia’s military capacity. Even in countries that have a strong political commitment to the sanctions’ regime, enforcement is weak. For instance, in Sweden, it is not illegal to try and evade sanctions according to the Swedish Chamber of Commerce (2024). There is little coordination between the numerous law enforcement agencies that are responsible for sanction enforcement and there have been very few investigations into sanctions violations.

Absent effective sanctions enforcement and for the many industries not covered by sanctions, can we rely on businesses to put profits second and voluntarily withdraw from Russia? Immediately after the start of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, as news stories about the brutality of the war proliferated, many international companies did announce that they will be leaving Russia. However, a more systematic look at data collected by the LeaveRussia project and KSE Institute reveals that more than two years into the war, less than half of companies based in Western democracies intend to distance themselves from the Russian market. A closer look at companies who are continuing operations in Russia reveals that they tend to be in sectors that are crucial for the Russian economy and war effort, such as energy, mining, electronics and industrial equipment. Many of these companies are probably seeing the war as a business opportunity and are reluctant to put human lives before their bottom line (Sonnenfeld and Tian, 2022).

Whether companies who announce that they are leaving Russia actually do leave is difficult to independently verify. A series of articles published in a prominent Swedish newspaper (Dagens Nyheter) last autumn revealed that goods from 14 major Swedish firms continue to be available in Russia, despite most of these firms publicly announcing their withdrawal from the country. The companies’ reactions to the exposé were mixed. A few companies, such as Scania and SSAB, have decided to cut all exports to the intermediaries exposed by the undercover journalists (for instance, in Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan). Other companies stated that they are currently investigating DN’s claims or that the exports exposed in the DN articles were final or delayed orders that were accepted before the company decided to withdraw from Russia. Another company, Trelleborg – a leading company within polymer solutions for a variety of industry purposes – reacted to the DN exposure by backtracking from its earlier commitment to exit the Russian market (Dagens Nyheter 2023b, 2023d). Wider reaction to these revelations was muted. Looking at changes in stock prices for the exposed companies, we find little evidence that investors are punishing companies for not honoring their public commitment to withdraw from Russia.

In an environment, where businesses themselves withdraw at low rates and investors do not shy away from companies contradicting their own claims, the need for stronger enforcement of sanctions seems more pressing than ever.

References

- Becker, T., Fredheim, K., Gars, J., Hilgenstock, B., Katinas, P., Le Coq, C., Mylovanov, T., Olofsgård, A., Perrotta Berlin, M., Pavytska, Y., Ribakova, E., Shapoval, N., Spiro, D. and Wachtmeister, H. (2024). Sanctions on Russia: Getting the Facts Right. FREE Policy Brief. https://freepolicybriefs.org/2024/03/14/sanctions-russia-war-ukraine/

- Bilousova, O., Hilgenstock, B., Ribakova, E., Shapoval, N., Vlasyuk, A. and Vlasiuk, V. (2024). CHALLENGES OF EXPORT CONTROLS ENFORCEMENT HOW RUSSIA CONTINUES TO IMPORT COMPONENTS FOR ITS MILITARY PRODUCTION. Yermak-McFaul International Working Group on Russian Sanctions & KSE Institute. https://kse.ua/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Challenges-of-Export-Controls-Enforcement.pdf

- Council of the European Union. (2023). Sanctions against Russia explained. European Council. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/sanctions-against-russia/sanctions-against-russia-explained/#services

- Dagens Nyheter. (2023a). DN avslöjar: Wallenbergs gruvjätte gjorde affärer med ryskgrundat bolag – efter krigsutbrottet.

- Dagens Nyheter. (2023b). DN avslöjar: Svenska storbolagen i affärer med Rvssland – trots löftena.

- Dagens Nyheter. (2023c). Svenska miljardbolaget svek löftet – sålde till ryska hamnprojekt.

- Dagens Nyheter (2023d). Mellanhanden avslöjar: Så levereras stålet från SSAB till Ryssland.

- Doherty, B. (2023). Business in Russia: Why some firms haven’t left. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20230918-business-in-russia-why-some-firms-havent-left

- Glambosky, M. and Peterburgsky, S. (2022). Corporate activism during the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Economics Letters, 217, 110650. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2022.110650

- Kiesel, F. and Kolaric, S. (2023) Should I stay or should I go? Stock market reactions to companies’ decisions in the wake of the Russia-Ukraine conflict. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, Forthcoming. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4088159

- LeaveRussia Project. (2024). https://leave-russia.org/our-methodology

- Lehne, J. (2022). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I1EFcZdj2Gw

- Olofsgård, A. and Smitt Meyer, C. (2024) How to Undermine Russia’s War Capacity: Insights from Development Day 2023. FREE Policy Brief. https://freepolicybriefs.org/2024/01/15/undermine-russias-war-capacity/

- Pandya, S. S., and Venkatesan, R. (2016) French roast: consumer response to international conflict—evidence from supermarket scanner data. Review of Economics and Statistics, 98(1), 42-56.

- Runfola, D., Rogers, L., Habib, J., Horn, S., Murphy, S., Miller, D., Day, H., Troup, L., Fornatora, D., Spage, N., Pupkiewicz, K., Roth, M., Rivera, C., Altman, C., Schruer, I., McLaughlin, T., Biddle, R., Ritchey, R., Topness, E., Turner, J., Updike, S., Buckman, H., Simpson, N., Lin, J., Anderson, A., Baier, H., Crittenden, M., Dowker, E., Fuhrig, S., Goodman, S., Grimsley, G., Layko, R., Melville, G., Mulder, M., Oberman, R., Panganiban, J., Peck, A., Seitz, L., Shea, S., Slevin, H., Yougerman, R. and Hobbs, L. (2020). geoBoundaries: A global database of political administrative boundaries. Plos One, 15(4), e0231866.

- Schwarzenberg. A. (2023). Russia’s Trade and Investment Role in the Global Economy. Congressional Research Services, Report IF12066. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF12066

- Sharma, R. (2023). Why markets are relatively calm in the geopolitical storm. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/d194a8a2-60c1-4afe-83bf-44e529e16d40

- Sonnenfeld, J. and Tian, S. (2022). Some of the Biggest Companies Are Leaving Russia. Others Just Can’t Quit Putin. Here’s a List. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/04/07/opinion/companies-ukraine-boycott.html

- Sonnenfeld, J., Tian, S., Sokolowski, F., Wyrebkowski, M., and Kasprowicz, M. (2022). Business Retreats and Sanctions Are Crippling the Russian Economy. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4167193

- Stockholms Handelskammare. (2022). Regionala handelsmönster med Ryssland. https://www.mynewsdesk.com/se/stockholmshandelskammare/documents/siffror-se-ru-punkt-pdf-420259

- Swedish Chamber of Commerce. (2024). Förslag på åtgärder mot kringgående av sanktioner. https://www.kommerskollegium.se/globalassets/publikationer/rapporter/2024/forslag-pa-atgarder-mot-kringgaenden-av-sanktioner.pdf

- S&P Global. (2024). Sanctions against Russia – a timeline. https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/news-insights/latest-news-headlines/sanctions-against-russia-8211-a-timeline-69602559

- Tidningen Näringslivet (2023). Svensk export till Rysslands grannar rusar. https://www.tn.se/naringsliv/30641/svensk-export-till-rysslands-grannar-rusar/

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in policy briefs and other publications are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect those of the FREE Network and its research institutes.

Navigating Environmental Policy Consistency Amidst Political Change

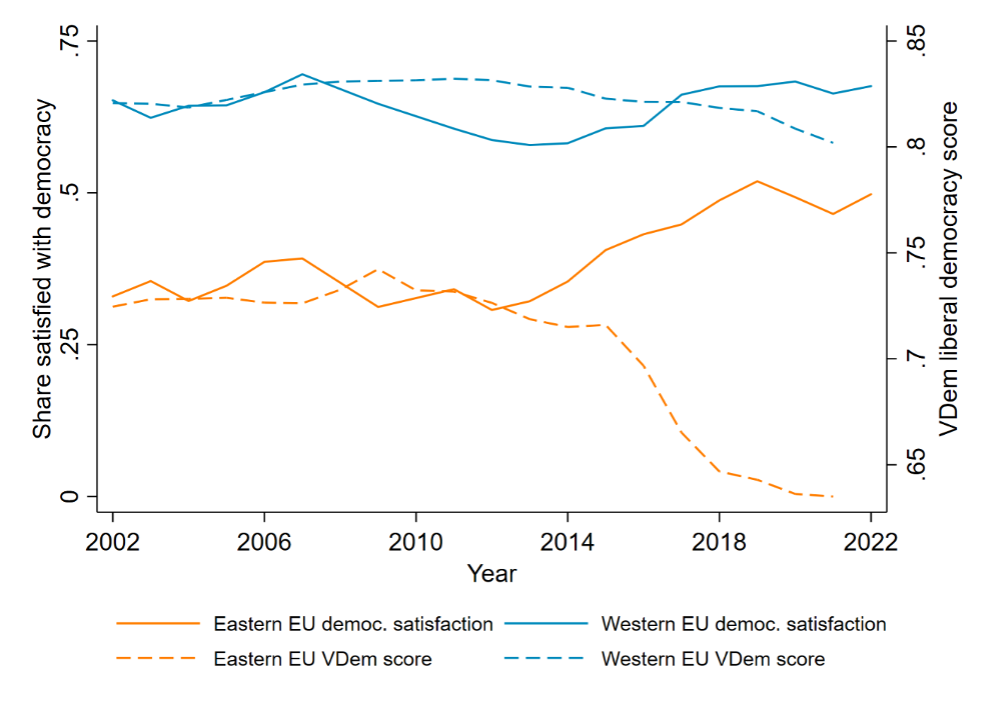

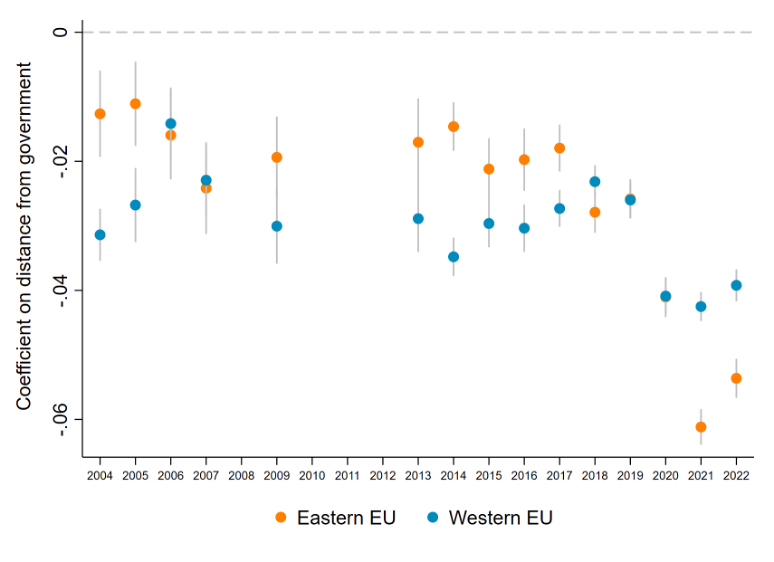

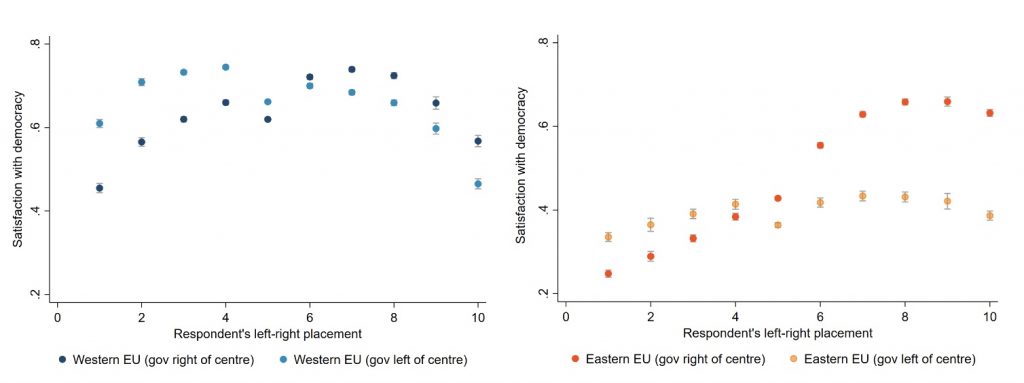

Europe, like other parts of the world, currently grapples with the dual challenges of environmental change and democratic backsliding. In a context marked by rising populism, misinformation, and political manipulation, designing credible sustainable climate policies is more important than ever. The 2024 annual Energy Talk, organized by the Stockholm Institute of Transition Economics (SITE), gathered experts to bring insight into these challenges and explore potential solutions for enhancing green politics.

In the last decades, the EU has taken significant steps to tackle climate change. Yet, there is much to be done to achieve climate neutrality by 2050. The rise of right-wing populists in countries like Italy and Slovakia, and economic priorities that overshadow environmental concerns, such as the pause of environmental regulations in France and reduced gasoline taxes in Sweden, are significantly threatening the green transition. The current political landscape, characterized by democratic backsliding and widespread misinformation, poses severe challenges for maintaining green policy continuity in the EU. The discussions at SITEs Energy Talk 2024 highlighted the need to incorporate resilience into policy design to effectively manage political fluctuations and ensure the sustainability and popular support of environmental policies. This policy brief summarizes the main points from the presentations and discussions.

Policy Sustainability

In his presentation, Michaël Aklin, Associate Professor of Economics and Chair of Policy & Sustainability at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne, emphasized the need for environmental, economic, and social sustainability into climate policy frameworks. This is particularly important, and challenging given that key sectors of the economy are difficult to decarbonize, such as energy production, transportation, and manufacturing. Additionally, the energy demand in Europe is expected to increase drastically (mainly due to electrification), with supply simultaneously declining (in part due to nuclear power phaseout in several member states, such as Germany). Increasing storage capacity, enhancing demand flexibility, and developing transmission infrastructure all require large, long-term investments, and uncompromising public policy. However, these crucial efforts are at risk due to ongoing political uncertainty. Aklin argued that a politics-resilient climate policy design is essential to avoid market fragmentation, decrease cooperation, and ensure the support for green policies. Currently, industrial policy is seen as the silver bullet, in particular, because it can create economies of scale and ensure political commitment to major projects. However, as Aklin explained, it is not an invincible solution, as such projects may also be undermined by capacity constraints and labour shortages.

Energy Policy Dynamics

Building on Aklin’s insights, Thomas Tangerås, Associate Professor at the Research Institute of Industrial Economics, explored the evolution of Swedish energy policy. Tangerås focused on ongoing shifts in support for nuclear power and renewables, driven by changes in government coalitions. Driven by an ambition to ensure energy security, Sweden historically invested in both hydro and nuclear power stations. In the wake of the Three Mile Island accident, public opinion however shifted and following a referendum in 1980, a nuclear shutdown by 2010 was promised. In the new millennia, the first push for renewables in 2003, was followed by the right-wing government’s nuclear resurgence in 2010, allowing new reactors to replace old ones. In 2016 there was a second renewable push when the left-wing coalition set the goal of 100 percent renewable electricity by 2040 (although with no formal ban on nuclear). This target was however recently reformulated with the election of the right-wing coalition in 2022, which, supported by the far-right party, launched a nuclear renaissance. The revised objective is to achieve 100 percent fossil-free electricity by 2040, with nuclear power playing a crucial role in the clean energy mix.

The back-and-forth energy policy in Sweden has led to high uncertainty. A more consistent policy approach could increase stability and minimize investment risks in the energy sector. Three aspects should be considered to foster a stable and resilient investment climate while mitigating political risks, Tangerås concluded: First, a market-based support system should be established; second, investments must be legally protected, even in the event of policy changes; and third, financial and ownership arrangements must be in place to protect against political expropriation and to facilitate investments, for example, through contractual agreements for advance power sales.

The Path to Net-Zero: A Polish Perspective

Circling back to the need for climate policy to be socially sustainable, Paweł Wróbel, Energy and climate regulatory affairs professional, Founder of GateBrussels, and Managing Director of BalticWind.EU, gave an account of Poland’s recent steps towards the green transition.

Poland is currently on an ambitious path of reaching net-zero, with the new government promising to step up the effort, backing a 90 percent greenhouse gas reduction target for 2040 recently proposed by the EU However, the transition is framed by geopolitical tensions in the region and the subsequent energy security issues as well as high energy prices in the industrial sector. Poland’s green transition is further challenged by social issues given the large share of the population living in coal mining areas (one region, Silesia, accounts for 12 percent of the polish population alone). Still, by 2049, the coal mining is to be phased out and coal in the energy mix is to be phased out even by 2035/2040 – optimistic objectives set by the government in agreement with Polish trade unions.

In order to achieve this, and to facilitate its green transition, Poland has to make use of its large offshore wind potential. This is currently in an exploratory phase and is expected to generate 6 GW by 2030, with a support scheme in place for an addition 12 GW. In addition, progress has been achieved in the adoption of solar power, with prosumers driving the progress in this area. More generally, the private sectors’ share in the energy market is steadily increasing, furthering investments in green technology. However, further investments into storage capacity, transmission, and distribution are crucial as the majority of Polands’ green energy producing regions lie in the north while industries are mainly found in the south.

Paralleling the argument of Aklin, Wróbel also highlighted that Poland’s high industrialization (with about 6 percent of the EU’s industrial production) may slow down the green transition due to the challenges of greening the energy used by this sector. The latter also includes higher energy prices which undermines Poland’s competitiveness on the European market.

Conclusion

The SITE Energy Talk 2024 catalyzed discussions about developing lasting and impactful environmental policies in times of political and economic instability. It also raised questions about how to balance economic growth and climate targets. To achieve its 2050 climate neutrality goals, the EU must implement flexible and sustainable policies supported by strong regulatory and political frameworks – robust enough to withstand economic and political pressures. To ensure democratic processes, it is crucial to address the threat posed by centralised governments decisions, political lock-ins, and large projects (with potential subsequent backlashes). This requires the implementation of fair policies, clearly communicating the benefits of the green transition.

On behalf of the Stockholm Institute of Transition Economics, we would like to thank Michaël Aklin, Thomas Tangerås and Paweł Wróbel for participating in this year’s Energy Talk.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in policy briefs and other publications are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect those of the FREE Network and its research institutes.

Greening Politics – Navigating Environmental Policy Consistency Amidst Political Change

The Stockholm Institute of Transition Economics (SITE) and the Forum for Research on Eastern Europe: Climate and Environment (FREECE) would like to invite you to its 2024 SITE Energy Talk. This edition will address the complexities of upholding environmental policies amidst a changing political landscape.

In the ongoing battle against climate change, maintaining our environmental commitments is more crucial than ever. However, the evolving landscape of global politics, marked by shifting international relations and significant concerns regarding democratic regression, presents escalating challenges to the continuity of our environmental objectives and obligations. This year’s SITE Energy Talk will prioritize the identification of risks posed by political transitions to our environmental aspirations and explore strategies for maintaining the credibility of environmental policies in the face of political flux.

Speakers

Michaël Aklin

Michaël Aklin, Associate Professor of Economics and holder of the Chair of Policy & Sustainability (PASU) at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne, who will offer a broader European perspective.

Thomas Tangerås

Thomas Tangerås

Thomas Tangerås, Associate Professor, Program Director at the Research Institute of Industrial Economics (IFN), who will address the Swedish perspective on the issue.

Paweł Wróbel

Paweł Wróbel, Energy and climate regulatory affairs professional. Founder of GateBrussels and Managing Director of BalticWind.EU, who will present Polish perspective on green transition in the face of European and regional challenges.

Registration

The event will take place in room Torsten, Sveavägen 65, 113 50 Stockholm (the main building of SSE) and the registration opens at 11.45 near room Torsten.

The event will also be streamed online via Zoom for those who cannot join the event in person. Please register via the Trippus platform:

NOTE: A light lunch will be provided for those who pre-register for in-person participation.

Please contact site@hhs.se if you have any questions regarding the event.

Highlights from Previous SITE Energy Talk Events

SITE Energy Talk is an annual event. The purpose is to bring together scholars and practitioners to discuss recent developments in the energy markets and regulation, such as:

- Energy infrastructure resilience and sustainable future (2023)

- Energy storage: Opportunities and challenges (2021)

- Energy demand management from a behavioral perspective (2018)

- Technological development, geopolitical and environmental issues in our energy future (2017)

- The impact of the technology changes on the energy market (2016)

- Economic impacts of oil price fluctuations (2015)

How to Undermine Russia’s War Capacity: Insights from Development Day 2023

As Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine continues, the future of the country is challenged by wavering Western financial and military support and weak implementation of the sanction’s regime. At the same time, Russia fights an information war, affecting sentiments for Western powers and values across the world. With these challenges in mind, the Stockholm Institute for Transition Economics (SITE) invited researchers and stakeholders to the 2023 Development Day Conference to discuss how to undermine Russia’s capacity to wage war. This policy brief shortly summarizes the featured presentations and discussions.

Holes in the Net of Sanctions

In one of the conference’s initial presentations Aage Borchgrevink (see list at the end of the brief for all presenters’ titles and affiliations) painted a rather dark picture of the current sanctions’ situation. According to Borchgrevink, Europe continuously exports war-critical goods to Russia either via neighboring countries (through re-rerouting), or by tampering with goods’ declaration forms. This claim was supported by Benjamin Hilgenstock who not only showed that technology from multinational companies is found in Russian military equipment but also illustrated (Figure 1) the challenges to export control that come from lengthy production and logistics chains and the various jurisdictions this entails.

Figure 1. Trade flows of war-critical goods, Q1-Q3, 2023.

Source: Benjamin Hilgenstock, Kyiv School of Economics Institute.

Offering a central Asian perspective, Eric Livny highlighted how several of the region’s economies have been booming since the enforcement of sanctions against Russia. According to Livny, European exports to Central Asian countries have in many cases skyrocketed (German exports to the Kyrgyzs Republic have for instance increased by 1000 percent since the invasion), just like exports from Central Asian countries to Russia. Further, most of the export increase from central Asian countries to Russia consists of manufactured goods (such as telephones and computers), machinery and transport equipment – some of which are critical for Russia’s war efforts. Russia has evidently made a major pivot towards Asia, Livny concluded.

This narrative was seconded by Michael Koch, Director at the Swedish National Board of Trade, who pointed to data indicating that several European countries have increased their trade with Russia’s neighboring countries in the wake of the decreased direct exports to Russia. It should be noted, though, that data presented by Borchgrevink showed that the increase in trade from neighboring countries to Russia was substantially smaller than the drop in direct trade with Russia from Europe. This suggests that sanctions still have a substantial impact, albeit smaller than its potential.

According to Koch, a key question is how to make companies more responsible for their business? This was a key theme in the discussion that followed. Offering a Swedish government perspective, Håkan Jevrell emphasized the upcoming adoption of a twelfth sanctions package in the EU, and the importance of previous adopted sanctions’ packages. Jevrell also continued by highlighting the urgency of deferring sanctions circumvention – including analyzing the effect of current sanctions. In the subsequent panel Jevrell, alongside Adrian Sadikovic, Anders Leissner, and Nataliia Shapoval keyed in on sanctions circumvention. The panel discussion brought up the challenges associated with typically complicated sanctions legislation and company ownership structures, urging for more streamlined regulation. Another aspect discussed related to the importance of enforcement of sanctions regulation and the fact that we are yet to see any rulings in relation to sanctions jurisdiction. The panelists agreed that the latter is crucial to deter sanctions violations and to legitimize sanctions and reduce Russian government revenues. Although sanctions have not yet worked as well as hoped for, they still have a bite, (for instance, oil sanctions have decreased Russian oil revenues by 30 percent).

Reducing Russia’s Government Revenues

As was emphasized throughout the conference, fossil fuel export revenues form the backbone of the Russian economy, ultimately allowing for the continuation of the war. Accounting for 40 percent of the federal budget, Russian fossil fuels are currently mainly exported to China and India. However, as presented by Petras Katinas, the EU has since the invasion on the 24th of February, paid 182 billion EUR to Russia for oil and gas imports despite the sanctions. In his presentation, Katinas also highlighted the fact that Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) imports for EU have in fact increased since the invasion – due to sanctions not being in place. The EU/G7 imposed price cap on Russian oil at $60 per barrel was initially effective in reducing Russian export revenues, but its effectiveness has over time being eroded through the emergence of a Russia controlled shadow fleet of tankers and sales documentation fraud. In order to further reduce the Russian government’s income from fossil fuels, Katinas concluded that the whitewashing of Russian oil (i.e., third countries import crude oil, refine it and sell it to sanctioning countries) must be halted, and the price cap on Russian oil needs to be lowered from the current $60 to $30 per barrel.