Location: Global

Gender Gap in Life Expectancy and Its Socio-Economic Implications

Today women live longer than men virtually in every country of the world. Although scientists still struggle to fully explain this disparity, the most prominent sources of this gender inequality are biological and behavioral. From an evolutionary point of view, female longevity was more advantageous for offspring survival. This resulted in a higher frequency of non-fatal diseases among women and in a later onset of fatal conditions. The observed high variation in the longevity gap across countries, however, points towards an important role of social and behavioral arguments. These include higher consumption of alcohol, tobacco, and fats among men as well as a generally riskier behavior. The gender gap in life expectancy often reaches 6-12 percent of the average human lifespan and has remained stubbornly stable in many countries. Lower life expectancy among men is an important social concern on its own and has significant consequences for the well-being of their surviving partners and the economy as a whole. It is an important, yet under-discussed type of gender inequality.

Country Reports

| Belarus Country Report | FROGEE POLICY BRIEF |

| Georgia Country Report | FROGEE POLICY BRIEF |

| Latvia Country Report | FROGEE POLICY BRIEF |

| Poland Country Report | FROGEE POLICY BRIEF |

Gender Gap in Life Expectancy and Its Socio-Economic Implications

Today, women on average live longer than men across the globe. Despite the universality of this basic qualitative fact, the gender gap in life expectancy (GGLE) varies a lot across countries (as well as over time) and scientists have only a limited understanding of the causes of this variation (Rochelle et al., 2015). Regardless of the reasons for this discrepancy, it has sizable economic and financial implications. Abnormal male mortality makes a dent in the labour force in nations where GGLE happens to be the highest, while at the same time, large GGLE might contribute to a divergence in male and female discount factors with implications for employment and pension savings. Large discrepancies in life expectancy translate into a higher incidence of widowhood and a longer time in which women live as widows. The gender gap in life expectancy is one of the less frequently discussed dimensions of gender inequality, and while it clearly has negative implications for men, lower male longevity has also substantial negative consequences for women and society as a whole.

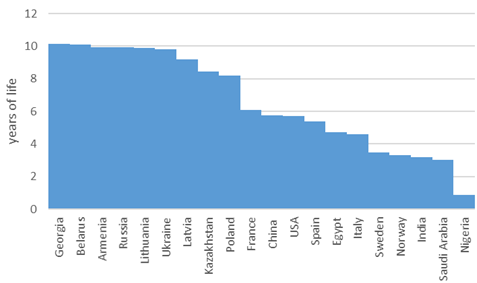

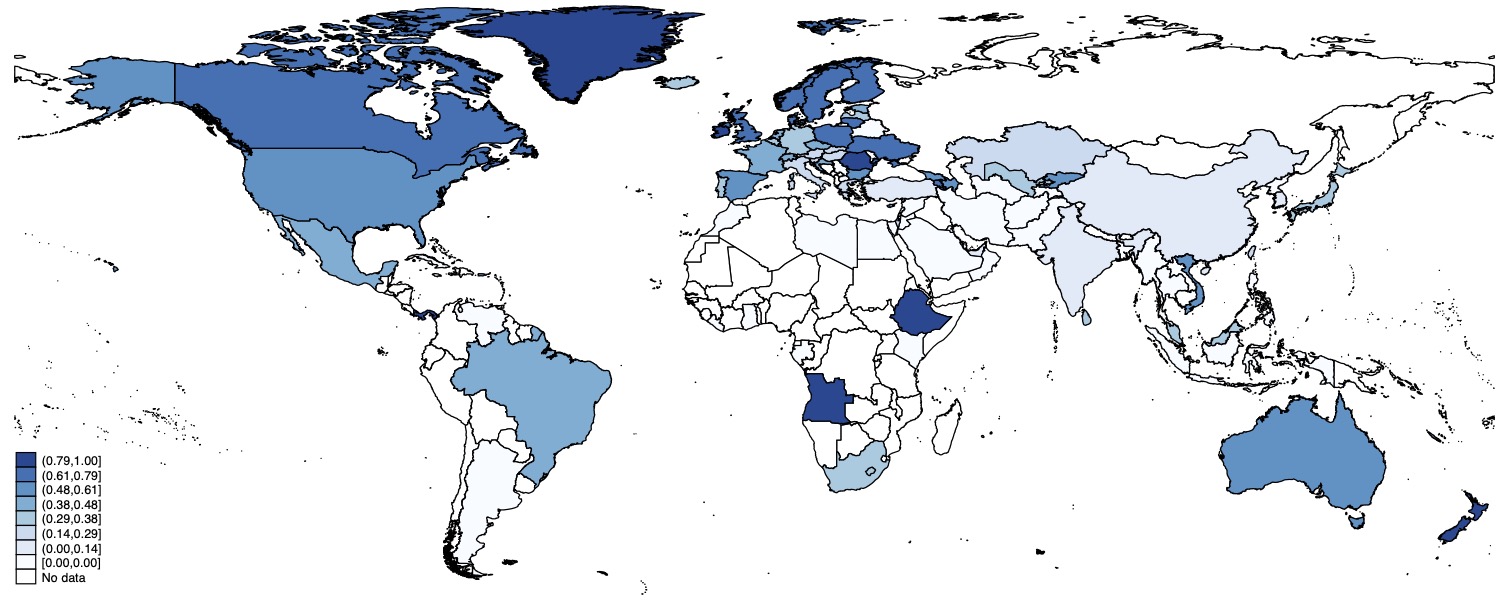

Figure A. Gender gap in life expectancy across selected countries

Source: World Bank.

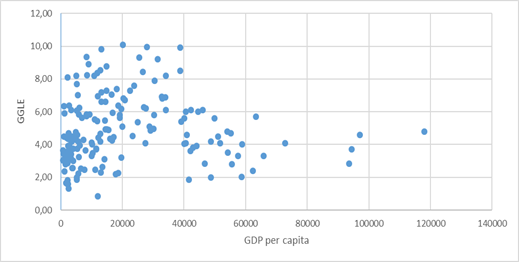

The earliest available reliable data on the relative longevity of men and women shows that the gender gap in life expectancy is not a new phenomenon. In the middle of the 19th century, women in Scandinavian countries outlived men by 3-5 years (Rochelle et al., 2015), and Bavarian nuns enjoyed an additional 1.1 years of life, relative to the monks (Luy, 2003). At the beginning of the 20th century, relative higher female longevity became universal as women started to live longer than men in almost every country (Barford et al., 2006). GGLE appears to be a complex phenomenon with no single factor able to fully explain it. Scientists from various fields such as anthropology, evolutionary biology, genetics, medical science, and economics have made numerous attempts to study the mechanisms behind this gender disparity. Their discoveries typically fall into one of two groups: biological and behavioural. Noteworthy, GGLE seems to be fairly unrelated to the basic economic fundamentals such as GDP per capita which in turn has a strong association with the level of healthcare, overall life expectancy, and human development index (Rochelle et al., 2015). Figure B presents the (lack of) association between GDP per capita and GGLE in a cross-section of countries. The data shows large heterogeneity, especially at low-income levels, and virtually no association from middle-level GDP per capita onwards.

Figure B. Association between gender gap in life expectancy and GDP per capita

Source: World Bank.

Biological Factors

The main intuition behind female superior longevity provided by evolutionary biologists is based on the idea that the offspring’s survival rates disproportionally benefited from the presence of their mothers and grandmothers. The female hormone estrogen is known to lower the risks of cardiovascular disease. Women also have a better immune system which helps them avoid a number of life-threatening diseases, while also making them more likely to suffer from (non-fatal) autoimmune diseases (Schünemann et al., 2017). The basic genetic advantage of females comes from the mere fact of them having two X chromosomes and thus avoiding a number of diseases stemming from Y chromosome defects (Holden, 1987; Austad, 2006; Oksuzyan et al., 2008).

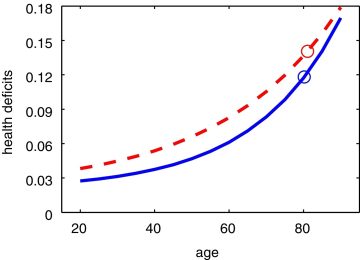

Despite a number of biological factors contributing to female longevity, it is well known that, on average, women have poorer health than men at the same age. This counterintuitive phenomenon is called the morbidity-mortality paradox (Kulminski et al., 2008). Figure C shows the estimated cumulative health deficits for both genders and their average life expectancies in the Canadian population, based on a study by Schünemann et al. (2017). It shows that at any age, women tend to have poorer health yet lower mortality rates than men. This paradox can be explained by two factors: women tend to suffer more from non-fatal diseases, and the onset of fatal diseases occurs later in life for women compared to men.

Figure C. Health deficits and life expectancy for Canadian men and women

Source: Schünemann et al. (2017). Note: Men: solid line; Women: dashed line; Circles: life expectancy at age 20.

Behavioural Factors

Given the large variation in GGLE, biological factors clearly cannot be the only driving force. Worldwide, men are three times more likely to die from road traffic injuries and two times more likely to drown than women (WHO, 2002). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the average ratio of male-to-female completed suicides among the 183 surveyed countries is 3.78 (WHO, 2024). Schünemann et al. (2017) find that differences in behaviour can explain 3.2 out of 4.6 years of GGLE observed on average in developed countries. Statistics clearly show that men engage in unhealthy behaviours such as smoking and alcohol consumption much more often than women (Rochelle et al., 2015). Men are also more likely to be obese. Alcohol consumption plays a special role among behavioural contributors to the GGLE. A study based on data from 30 European countries found that alcohol consumption accounted for 10 to 20 percent of GGLE in Western Europe and for 20 to 30 percent in Eastern Europe (McCartney et al., 2011). Another group of authors has focused their research on Central and Eastern European countries between 1965 and 2012. They have estimated that throughout that time period between 15 and 19 percent of the GGLE can be attributed to alcohol (Trias-Llimós & Janssen, 2018). On the other hand, tobacco is estimated to be responsible for up to 30 percent and 20 percent of the gender gap in mortality in Eastern Europe and the rest of Europe, respectively (McCartney et al., 2011).

Another factor potentially decreasing male longevity is participation in risk-taking activities stemming from extreme events such as wars and military activities, high-risk jobs, and seemingly unnecessary health-hazardous actions. However, to the best of our knowledge, there is no rigorous research quantifying the contribution of these factors to the reduced male longevity. It is also plausible that the relative importance of these factors varies substantially by country and historical period.

Gender inequality and social gender norms also negatively affect men. Although women suffer from depression more frequently than men (Albert, 2015; Kuehner, 2017), it is men who commit most suicides. One study finds that men with lower masculinity (measured with a range of questions on social norms and gender role orientation) are less likely to suffer from coronary heart disease (Hunt et al., 2007). Finally, evidence shows that men are less likely to utilize medical care when facing the same health conditions as women and that they are also less likely to conduct regular medical check-ups (Trias-Llimós & Janssen, 2018).

It is possible to hypothesize that behavioural factors of premature male deaths may also be seen as biological ones with, for example, risky behaviour being somehow coded in male DNA. But this hypothesis may have only very limited truth to it as we observe how male longevity and GGLE vary between countries and even within countries over relatively short periods of time.

Economic Implications

Premature male mortality decreases the total labour force of one of the world leaders in GGLE, Belarus, by at least 4 percent (author’s own calculation, based on WHO data). Similar numbers for other developed nations range from 1 to 3 percent. Premature mortality, on average, costs European countries 1.2 percent of GDP, with 70 percent of these losses attributable to male excess mortality. If male premature mortality could be avoided, Sweden would gain 0.3 percent of GDP, Poland would gain 1.7 percent of GDP, while Latvia and Lithuania – countries with the highest GGLE in the EU – would each gain around 2.3 percent of GDP (Łyszczarz, 2019). Large disparities in the expected longevity also mean that women should anticipate longer post-retirement lives. Combined with the gender employment and pay gap, this implies that either women need to devote a larger percentage of their earnings to retirement savings or retirement systems need to include provisions to secure material support for surviving spouses. Since in most of the retirement systems the value of pensions is calculated using average, not gender-specific, life expectancy, the ensuing differences may result in a perception that men are not getting their fair share from accumulated contributions.

Policy Recommendations

To successfully limit the extent of the GGLE and to effectively address its consequences, more research is needed in the area of differential gender mortality. In the medical research dimension, it is noteworthy that, historically, women have been under-represented in recruitment into clinical trials, reporting of gender-disaggregated data in research has been low, and a larger amount of research funding has been allocated to “male diseases” (Holdcroft, 2007; Mirin, 2021). At the same time, the missing link research-wise is the peculiar discrepancy between a likely better understanding of male body and health and the poorer utilization of this knowledge.

The existing literature suggests several possible interventions that may substantially reduce premature male mortality. Among the top preventable behavioural factors are smoking and excessive alcohol consumption. Many studies point out substantial country differences in the contribution of these two factors to GGLE (McCartney, 2011), which might indicate that gender differences in alcohol and nicotine abuse may be amplified by the prevailing gender roles in a given society (Wilsnack et al., 2000). Since the other key factors impairing male longevity are stress and risky behaviour, it seems that a broader societal change away from the traditional gender norms is needed. As country differences in GGLE suggest, higher male mortality is mainly driven by behaviours often influenced by societies and policies. This gives hope that higher male mortality could be reduced as we move towards greater gender equality, and give more support to risk-reducing policies.

While the fundamental biological differences contributing to the GGLE cannot be changed, special attention should be devoted to improving healthcare utilization among men and to increasingly including the effects of sex and gender in medical research on health and disease (Holdcoft, 2007; Mirin, 2021; McGregor et al., 2016, Regitz-Zagrosek & Seeland, 2012).

References

- Albert, P. R. (2015). “Why is depression more prevalent in women?“. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience, 40(4), 219.

- Austad, S. N. (2006). “Why women live longer than men: sex differences in longevity“. Gender Medicine, 3(2), 79-92.

- Barford, A., Dorling, D., Smith, G. D., & Shaw, M. (2006). “Life expectancy: women now on top everywhere“. BMJ, 332, 808. doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7545.808

- Holden, C. (1987). “Why do women live longer than men?“. Science, 238(4824), 158-160.

- Hunt, K., Lewars, H., Emslie, C., & Batty, G. D. (2007). “Decreased risk of death from coronary heart disease amongst men with higher ‘femininity’ scores: A general population cohort study“. International Journal of Epidemiology, 36, 612-620.

- Kulminski, A. M., Culminskaya, I. V., Ukraintseva, S. V., Arbeev, K. G., Land, K. C., & Yashin, A. I. (2008). “Sex-specific health deterioration and mortality: The morbidity-mortality paradox over age and time“. Experimental Gerontology, 43(12), 1052-1057.

- Luy, M. (2003). “Causes of Male Excess Mortality: Insights from Cloistered Populations“. Population and Development Review, 29(4), 647-676.

- McCartney, G., Mahmood, L., Leyland, A. H., Batty, G. D., & Hunt, K. (2011). “Contribution of smoking-related and alcohol-related deaths to the gender gap in mortality: Evidence from 30 European countries“. Tobacco Control, 20, 166-168.

- McGregor, A. J., Hasnain, M., Sandberg, K., Morrison, M. F., Berlin, M., & Trott, J. (2016). “How to study the impact of sex and gender in medical research: A review of resources“. Biology of Sex Differences, 7, 61-72.

- Mirin, A. A. (2021). “Gender disparity in the funding of diseases by the US National Institutes of Health“. Journal of Women’s Health, 30(7), 956-963.

- Oksuzyan, A., Juel, K., Vaupel, J. W., & Christensen, K. (2008). “Men: good health and high mortality. Sex differences in health and aging“. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 20(2), 91-102.

- Regitz-Zagrosek, V., & Seeland, U. (2012). “Sex and gender differences in clinical medicine“. Sex and Gender Differences in Pharmacology, 3-22.

- Rochelle, T. R., Yeung, D. K. Y., Harris Bond, M., & Li, L. M. W. (2015). “Predictors of the gender gap in life expectancy across 54 nations“. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 20(2), 129-138. doi:10.1080/13548506.2014.936884

- Schünemann, J., Strulik, H., & Trimborn, T. (2017). “The gender gap in mortality: How much is explained by behavior?“. Journal of Health Economics, 54, 79-90.

- Trias-Llimós, S., & Janssen, F. (2018). “Alcohol and gender gaps in life expectancy in eight Central and Eastern European countries“. European Journal of Public Health, 28(4), 687-692.

- WHO. (2002). “Gender and road traffic injuries“. World Health Organization.

- WHO. (2024). “Global health estimates: Leading causes of death“. World Health Organization.

- Łyszczarz, B. (2019). “Production losses associated with premature mortality in 28 European Union countries“. Journal of Global Health.

About FROGEE Policy Briefs

FROGEE Policy Briefs is a special series aimed at providing overviews and the popularization of economic research related to gender equality issues. Debates around policies related to gender equality are often highly politicized. We believe that using arguments derived from the most up to date research-based knowledge would help us build a more fruitful discussion of policy proposals and in the end achieve better outcomes.

The aim of the briefs is to improve the understanding of research-based arguments and their implications, by covering the key theories and the most important findings in areas of special interest to the current debate. The briefs start with short general overviews of a given theme, which are followed by a presentation of country-specific contexts, specific policy challenges, implemented reforms and a discussion of other policy options.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in policy briefs and other publications are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect those of the FREE Network and its research institutes.

Russia in Africa: What the Literature Reveals and Why It Matters

Following the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February, 2022, Russia has become increasingly isolated. In an attempt to counter Western powers’ efforts to suppress its economy and soft power impacts, Russia has tried to increase its influence in other parts of the world. In particular, Russia is increasingly active on the African continent, having become a key partner to several African regimes, typically operating in areas with weak institutions and governments. Additionally, Russia’s approach has a different focus and objectives compared to other foreign actors, which may have both short and long term consequences for the continent’s development. Deepening our understanding of Russia’s distinct approach alongside those of other global actors, as well as the future implications of their involvement on the continent is, thus, of crucial importance.

Introduction

The new Foreign Policy Concept, adopted by the Russian government in March 2023, dedicates, for the first time, a separate section to Africa. The previous versions of the policy grouped North Africa with the Middle East and contained only a single paragraph, kept unchanged over time, about Sub-Saharan Africa. In the midst of its war against Ukraine, Russia is getting serious about Africa. What do we know about the reasons for and implications of this trend?

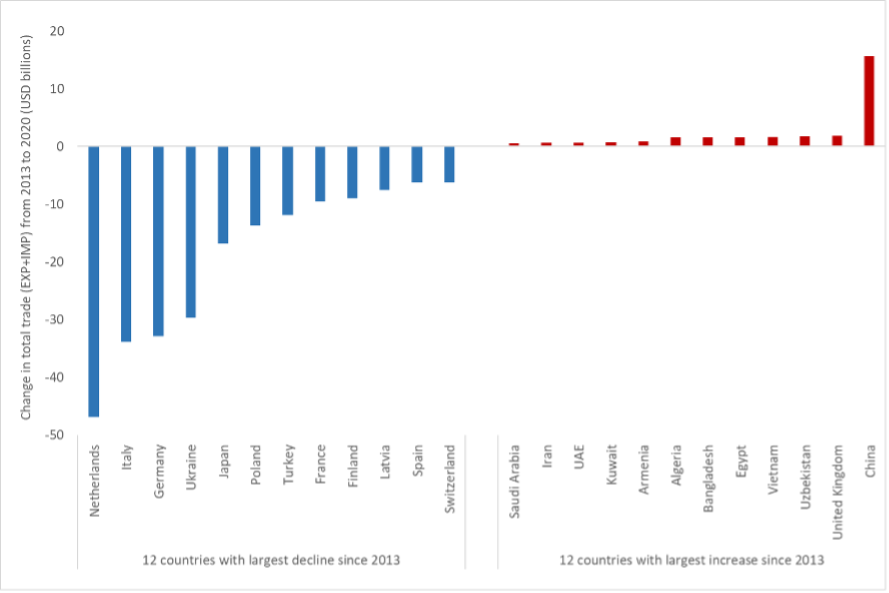

A relatively large literature in economics, political science, international relations, and other related fields has dealt with the Soviet Union’s engagement with African regimes (see overviews in Morris, 1973 and Ramani, 2023). However, the number of studies following the evolution of these relations since the collapse of the Soviet Union is significantly smaller, reflecting Russia’s strategic withdrawal from the region between 1990 and 2015. Following the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russia’s increased interest in and engagement on the African continent has been increasingly discussed by security analysts and think tanks (see for instance Siegel, 2021; Stanyard, Vircoulon and Rademeyer, 2023; Jones, et al., 2021). Primarily highlighted are Russia’s interest in mineral deposits, its large-scale arms’ exports to African regimes, its dominance on the nuclear energy market with resulting dependency on Russian nuclear fuels, and its ambition to undermine Western capacities by the spread of Russian propaganda and anti-Western sentiments (Lindén, 2023). Each of these dimensions carries potentially profound and far-reaching implications for the continent’s development, as underscored by various strands of literature. Research contributions on this specific new trend are however still very limited and predominantly of a qualitative and exploratory nature.

There is, however, substantial general knowledge about the various forms that foreign interests can take, including trade, investment, development aid, propaganda, election interference, and involvement in conflicts, and their potential consequences for development. This brief presents an overview of selected literature that most closely relates to foreign influence in Africa.

Background: Theories of Foreign Policy

Two contrasting approaches are used to describe the way countries engage with the international community. The first one is the so-called realist perspective, which emphasizes the role of power, national interests, and security in shaping foreign policy (Mearsheimer, 1995). In this model, countries act in their self-interest, and often in competition or even conflict with other countries. Strategic alliances and a willingness to use force to advance one’s interests are contemplated under this perspective. The second approach is the idealist perspective, in which foreign policy is used to promote democratic values, human rights, and international cooperation, prioritizing tools such as diplomacy, international law, and multilateral institutions (Lancaster, 2008). For countries at the receiving end of major powers’ foreign policy agendas, and particularly for developing countries, the implications from the contrasting approaches will be widely different. While even a realist foreign policy may ostensibly incorporate concerns about the welfare and development of its allies, these are often not more than a thin disguise for the ultimate objective of buying political support and commercial advantages. A genuine interest in the welfare and development of receiving partners only finds a place under the idealist perspective, although even idealism is at times claimed to “greenwash” state actors’ own interests (Delmas and Burbano, 2011). While this claim has some substance to it, such accusations can also stem from the anti-western rhetoric typically pursued by Russia and aimed at undermining the credibility of actors with good intentions.

In practice, most countries’ foreign policies incorporate elements of both realism and idealism, although the balance between the two may vary. Some countries may have a predominantly realist approach, while others may prioritize idealist goals. Additionally, the same country may shift its approach over time, depending on changing circumstances and priorities. Idealism may be more prominent during periods of stability and prosperity, when countries have the resources and political will to pursue more ambitious foreign policy goals. Realism tends to become more prominent in times of crisis, when countries face serious threats to their national security or economic well-being. Historical examples of the latter are the aftermath of World War II, the Cold War, and even the 2008 global financial crisis (Roberts, 2020).

Comparative Analysis of Foreign Influence

A few studies, recent enough to encompass Russia’s renewed interest in Africa post-2015 but not enough to cover the current day resurgence, explicitly compare the strategy of different actors and their long-term influence. Trunkos (2021) develops a new soft power measure for the time-period 1995–2015, to test the commonly accepted claim in the political science literature that American soft power use has been declining while Russian and Chinese soft power use has been increasing. In the author’s own words, “the findings indicate that surprisingly the US is still using more soft power than Russia and China. The data analysis also reveals that the US is leading in economic soft power actions over China and in military soft power actions over Russia as well.”

Castaneda Dower et al. (2021) take a longer-term perspective and categorize African countries into two blocs one Western-leaning and one pro-Soviet, based on a game-theoretical model of alliances. This categorization aligns well with UN voting patterns during the Cold War, but it does not predict alignment as effectively in the post-Cold War period. The study finds no significant difference in average GDP growth between the two blocs for the period from 1990 to 2016. However, the bloc with Western-like characteristics shows higher levels of inequality and greater reliance on the market economy – as opposed to the planned one. It also has higher human capital, more gender parity (in education), and better democracy scores, but lower infrastructure capital compared to the other bloc.

Another strand of literature has looked into the deep changes that have occurred over time within the global development architecture, highlighting changes in donor and partner motivations after the end of the Cold War (Boschini and Olofsgård, 2007; Frot, Olofsgård and Perrotta Berlin, 2014), through the Arab Spring (Challand, 2014), and more recently under the emergence of new actors, chiefly China (Blair, Marty and Roessler, 2021). Studies in this area aim to highlight what implications the varying ideologies and motivation for cooperation in the donor countries have for countries at the receiving end. Competing aid regimes generate soft power through public diplomacy, often in the form of branding (for instance through putting origin “flags” on aid projects or investments). This type of positive association has been shown to generate ‘positive affect’ toward donors (Andrabi and Das, 2010), and to strengthen recipients’ perceptions of the models of governance and development that such donors promote – liberal democracy, for example, or free market capitalism (Blair, Marty and Roessler, 2021).

Emerging Players on the African Stage

An extensive literature has examined the various facets of established power actors’ presence on the continent, spanning foreign aid, diplomatic relations, and military involvement, revealing significant impacts on local economic development through multiple channels. The United States, along with other former colonial powers and major Western donors, plays a particularly prominent role in this context. Against this background, recent research has increasingly focused on the rise of new actors, and in particular China’s expanding role as a donor and investor in Africa (Bluhm, 2018; Brautigam, 2008; Brazys, Elkink and Kelly, 2017; Dreher et al. 2018). While the consensus is still unclear on whether China’s approach to aid attracts support among African citizens (Lekorwe et al. 2016; Blair, Marty, and Roessler, 2021), recent research also shows that Chinese aid exacerbates corruption and undermines collective bargaining in recipient countries (Isaksson and Kotsadam 2018a; 2018b).

As mentioned, there are as yet very few recent articles concerned with the reasons for Russia’s renewed interest in Africa (see Marten, 2019; Akinlolu and Ogunnubi, 2021; Ramani, 2023), and even fewer analyzing the potential impacts from it. One working paper, not citable due to the authors’ wishes, has quantitatively mapped and explicitly analyzed the impact of Russian military presence (in particular, of the Wagner Group) in Africa. The study found that the infamous paramilitary group faces fewer repercussions for human rights violations and commits more lethal actions than the state actors that employ them. In another recent study on the Central African Republic (CAR), Gang et al. (2023) found not only mortality levels in CAR to be four times higher than what estimated by the UN but also that Wagner mercenaries have contributed to “increased difficulties of survival” for the population in affected areas. Pardyak, M. (2022) explores the communication strategies employed by the key actors in the war, specifically focusing on how these strategies are received in African societies. Based on the analysis of over 140 media articles published in several African countries up to 15 October 2022, complemented by street surveys in Cairo, and in-depth interviews with Egyptians and Sudanese migrants, the study concludes that Russia’s multipolar perspective on the international order is more widely supported in Africa than Western strategies.

When viewed in a historical context, however, Russia’s actions reflect a longstanding adherence to a realist approach in its foreign policy endeavors. Throughout its trajectory, Russia has consistently prioritized national security and economic interests, frequently leveraging military and economic means to safeguard these interests (Tsygankov and Tsygankov, 2010). Presently, amid mounting pressures from the Western democratic world following the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Russia finds itself increasingly reliant on a realist approach. While the Chinese engagement in Africa is also characterized by realist principles, it’s important to emphasize that the Russian approach diverges from that of China. China is focused on a long-term presence, infrastructure building and investments. It has no interest in democracy and human rights, is efficient and cheap though not always loved (Isaksson and Kotsadam, 2018b). Russia’s interest is more short term and opportunistic, seeking out countries rich in natural resources with unstable governments and weak institutions, such as Libya, Sudan, Mozambique, the Central African Republic, Mali, Burkina Faso and Madagascar. Russia typically targets undemocratic elites or military juntas, offering political support, military equipment sales, and security cooperation (in particular through the Wagner Group) in exchange for access to natural resources, concession rights and influence. State of the art research on a previous period (Berman et al., 2017, spanning 1997 to 2010), although not exclusively focused on Russia, finds that rents from mineral contracts, captured by swings in global mineral prices for a causal interpretation, lead to a higher likelihood of local conflicts, and furthermore that the control of mining areas by rebel groups can escalate violence beyond the local level.

Russia is pursuing a range of strategic goals that include diplomatic legitimization, media influence, military presence, elite influence, arms export, and shaping voting patterns in international organizations (Lindén, 2023). Like China, Russia is uninterested in democracy or human rights. Moreover, what Russia stands for is in stark contrast to the Western model. Russia embodies autocracy and backward revisionist values (for instance in areas such as attitudes to gender equality and the sustainability agenda) while the West generally promotes democracy and progressive inclusive solutions (Lindén, 2023). What also especially characterizes Russia is the particular attraction towards the presence of anti-West sentiment, which it fuels through populistic anti-colonial disinformation and propaganda. This approach has been criticized for potentially weakening democratic norms and sidelining African agency (Akinlolu and Ogunnubi, 2021). Additionally, Russia’s disregard for the socio-political realities in Africa, typically associated with a self-interested realist approach, can lead to ineffective engagement and unintended negative consequences, undermining the long-term sustainability of both social and economic developments in the region.

Conclusion

Many African countries find themselves in a delicate balancing act, as they cannot afford to push away Russia nor displease their historical Western partners. This attempt to balance between actors poses several risks and potentially detrimental consequences, including reduced development cooperation, slower democratization, limited progress on human rights, and increased conflicts. Additionally, Russia’s growing presence in Africa can have implications for the interests and policies of the European Union (EU) and its member states as well as global actors, including impacts on migration, terrorism, the energy sector as well as on trade and aid flows.

In light of the diverse strategies foreign powers use in their relations with African countries and the significant impact these strategies have, it is crucial to deepen our understanding of foreign engagements in Africa. By examining Russia’s distinct approach alongside those of other global actors, we can gain valuable insights into the complex dynamics shaping the continent’s political, economic, and social landscape, both now and in the future. Expanding research in this area is not only desirable but essential for informing policy and development strategies.

References

- Akinlolu E. A. and Ogunnubi, O. (2021). Russo-African Relations and electoral democracy: Assessing the implications of Russia’s renewed interest for Africa, African Security Review, 30:3, 386-402, DOI: 10.1080/10246029.2021.1956982

- Andrabi, T., & Das, J. (2010). In Aid We Trust: Hearts and Minds and the Pakistan Earthquake of 2005. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, (5440).

- Berman, N., Couttenier, M., Rohner, D., & Thoenig, M. (2017). This Mine is Mine! How Minerals Fuel Conflicts in Africa. American Economic Review, 107(6), 1564-1610.

- Challand, B. (2014). Revisiting Aid in the Arab Middle East. Mediterranean Politics, 19(3), 281-298. DOI: 10.1080/13629395.2014.966983

- Blair, R. A., Marty, R., and Roessler, P. (2021). Foreign Aid and Soft Power: Great Power Competition in Africa in the Early Twenty-first Century. British Journal of Political Science, 52(3), 1355–1376. doi:10.1017/S0007123421000193

- Bluhm, R., et al. (2018). Connective Financing: Chinese Infrastructure Projects and the Diffusion of Economic Activity in Developing Countries. AidData Working Paper 64.

- Boschini, A., and Olofsgård, A. (2007). Foreign aid: An instrument for fighting communism? The Journal of Development Studies, 43(4), 622-648. DOI: 10.1080/00220380701259707

- Brautigam, D. (2009). The Dragon’s Gift: The Real Story of China in Africa. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Castaneda Dower, P., Gokmen, G., Le Breton, M., & Weber, S. (2021). Did the Cold War Produce Development Clusters in Africa? (Working Papers; No. 2021:10).

- Delmas, M. A. and Burbano, V. C. (2011). The Drivers of Greenwashing. California Management Review, 54(1), 64-87.

- Dreher, A., et al. (2018). Apples and dragon fruits: The determinants of aid and other forms of state financing from China to Africa. International Studies Quarterly, 62(1), 182–194.

- Frot, E., Olofsgård, A., and Perrotta Berlin, M. (2014). Aid Effectiveness in Times of Political Change: Lessons from the Post-Communist Transition. World Development, 56, 127-138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.10.016

- Isaksson, A-S., and Kotsadam, A. (2018a). Chinese aid and local corruption. Journal of Public Economics, 159, 146–159.

- Isaksson, A-S., and Kotsadam, A. (2018b). Racing to the bottom? Chinese development projects and trade union involvement in Africa. World Development, 106, 284–298.

- Jones, S. G., Doxsee, C., Katz, B., McQueen, E. and Moye, J. (2021). Russia’s Corporate Soldiers. The Global Expansion of Russia’s Private Military Companies. A Report of the CSIS Transnational Threats Project. CSIS. https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/210721_Jones_Russia%27s_Corporate_Soldiers.pdf?VersionId=7fy3TGV3HqDtRKoe8vDq2J2GGVz7N586

- Gang, K. B. A., O’Keeffe, J., Anonymous et al. (2023). Cross-sectional survey in Central African Republic finds mortality 4-times higher than UN statistics: how can we not know the Central African Republic is in such an acute humanitarian crisis?. Conflict and Health, 17(21). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-023-00514-z

- Lancaster, C. (2008). Foreign aid: Diplomacy, development, domestic politics. University of Chicago Press.

- Lekorwe, M., et al. (2016). China’s growing presence in Africa wins largely positive popular reviews. Afrobarometer Dispatch, 122.

- Lindén, K. (2023). Russia’s relations with Africa: Small, military-oriented and with destabilising effects. FOI Memo 8090. https://www.foi.se/rapportsammanfattning?reportNo=FOI%20Memo%208090

- Marten, K. (2019). Russia’s use of semi-state security forces: the case of the Wagner Group, Post-Soviet Affairs, 35:3, 181-204, DOI: 10.1080/1060586X.2019.1591142

- Mearsheimer, J. (1995). A Realist Reply. International Security, 20(1), 82-93. https://doi.org/10.2307/2539218

- Morris, M. D. (1973). The Soviet Africa Institute and the development of African studies. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 11(2), 247-265.

- Olofsgård, A., Perrotta Berlin, M. and Bonnier, E. (2023). Foreign Aid and Female Empowerment. SITE Working Paper Series, No. 62.

- Pardyak, M. (2022). Fighting for Africans’ Hearts and Minds in the Context of the 2022 War in Ukraine. Journal of Central and Eastern European African Studies, 2(4), 158-194.

- Ramani, Samuel, Russia in Africa: Resurgent Great Power or Bellicose Pretender? (2023; online edn, Oxford Academic, 28 Sept. 2023), https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197744598.001.0001

- Roberts, A. (2020). “Whatever It Takes”: Danger, Necessity, and Realism in American Public Policy. Administration & Society, 52(7), pp. 1131-1144. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399720938550

- Siegel, J. (2021). Herd, P. G. (ed). Russia’s Global Reach: A Security and Statecraft Assessment. Garmisch-Partenkirchen: George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies. https://www.marshallcenter.org/en/publications/marshall-center-books/russias-global-reach-security-and-statecraft-assessment

- Stanyard, J., Vircoulon, T. and Rademeyer, J. (2023). The grey zone: Russia’s military, mercenary and criminal engagement in Africa. The Global Intitaive against transnational organized crime. https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Julia-Stanyard-T-Vircoulon-J-Rademeyer-The-grey-zone-Russias-military-mercenary-and-criminal-engagement-in-Africa-GI-TOC-February-2023-v3-1.pdf

- Trunkos, J. (2021) Comparing Russian, Chinese and American Soft Power Use: A New Approach, Global Society, 35:3, 395-418, DOI: 10.1080/13600826.2020.1848809

- Tsygankov, A. P., & Tsygankov, P. A. (2010). Russian theory of international relations. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of International Studies.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in policy briefs and other publications are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect those of the FREE Network and its research institutes.

Why the National Bank of Georgia Is Ditching Dollars for Gold

The National Bank of Georgia (NBG) recently acquired 7 tons of high-quality monetary gold valued at $500 million, constituting approximately 11 percent of the banks’ total reserves. This marked the first occasion that Georgia acquired gold for its reserves since regaining its independence. The acquisition is a significant event, prompted by the NBG’s stated aim to enhance diversification amidst increased global geopolitical risks. However, diversification is just one of the reasons many countries are extensively purchasing gold. Another reason for increasing gold reserves is to lessen one’s reliance on the US dollar and to protect against sanctions, as seen with Russia and Belarus following the annexation of Crimea. While the NBG’s gold acquisition aligns with economic rationale, recent domestic developments suggest other motives. Actions like sanctions on political figures, anti-Western rhetoric, and recent legislation (the Law of Transparency of Foreign Influence), diverging Georgia from an EU pathway call for speculation that the gold purchase is driven by fear a of potential sanctions and as a preparedness strategy.

Introduction

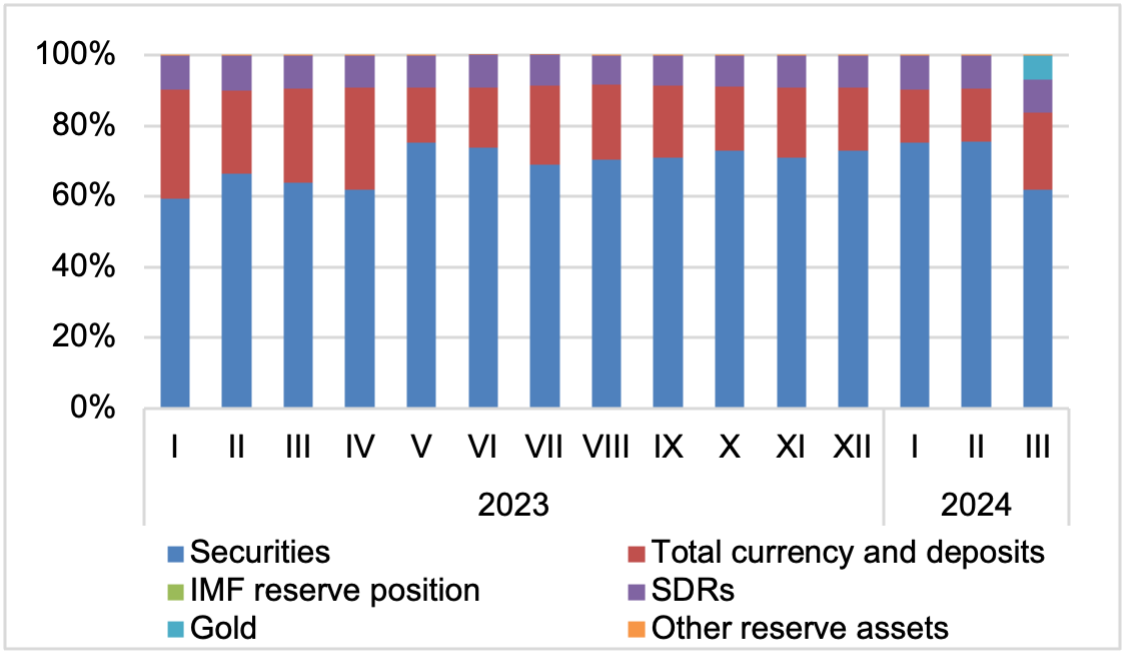

The National Bank of Georgia (NBG) has broken new ground by adding gold to the country’s international reserves for the first time ever. Georgia has thus become the first country in the South Caucasus to purchase gold for its reserves. In line with its Board’s decision on March 1, 2024, the NBG procured 7 tons of the highest quality (999.9) monetary gold. The acquisition, valued at 500 million US dollars, took the form of internationally standardized gold bars, purchased from the London gold bar market and currently stored in London. Presently, the acquired gold represents approximately 11 percent of the NBG’s international reserves (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. NBG’s Official Reserve Assets and Other Foreign Currency Assets, 2023-2024.

Source: The National Bank of Georgia.

The NBG emphasizes in its official statement that the acquisition of gold is not merely symbolic but rather reflects a deliberate strategy of diversifying NBG’s portfolio and enhancing its resilience to external shocks. The NBG’s decision was made during a period marked by significant economic and political events both within and outside Georgia. Key among these were global and regional geopolitical tensions that amplified concerns about economic downturns and rising inflation. The Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 led to stagflation across many countries, including Georgia. Despite some recovery in GDP, high inflation continued into 2021. Furthermore, the Russian war on Ukraine disrupted supply chains, and pushed global inflation to a 24-year high 8.7 percent in 2022. In response, stringent monetary policies aimed at controlling inflation were implemented across both developing and advanced economies. Looking ahead, there is an expectation of a shift toward more expansionary monetary policies that should help lower interest rates (and lower yields on assets held by central banks). These global conditions provide context for the NBG’s strategic focus on diversification.

However, alongside these economic events, Georgia also faces significant political challenges. Since the beginning of Russia’s war in Ukraine in 2022, political tensions in Georgia have escalated. Notable actions such as the U.S. imposing sanctions on influential Georgian figures, including judges and the former chief prosecutor, have, among other things, intensified scrutiny into the Russian influence in Georgia. Concerns about the independence of the Central Bank, which changed the rule of handling sanctions applications for Georgia’s citizens, and legislative initiatives like the Law of Transparency of Foreign Influence, which undermines Georgia’s EU accession ambitions, have triggered reactions from the country’s partners and massive public protests. Moreover, anti-Western rhetoric from the ruling party has raised concerns. In addition, the parliament of Georgia recently approved an amendment to the Tax Cide, a so-called ‘law on offshores’. The opaque nature of the law, as well as the context and speed at which it was advanced, sparked outcry and conjecture about its true purpose. These elements lead to speculation that the decision to purchase gold may be motivated by a desire for greater autonomy or a fear of potential sanctions, rather than purely economic reasons.

In the context of the above, this policy brief seeks to explore the motivations behind gold acquisitions by Central Banks, drawing on the experiences of both developed and developing countries. It aims to review existing literature that explores various reasons for gold acquisitions, providing a comprehensive analysis of economic and potentially non-economic factors influencing such decisions.

The Return of Gold in Global Finance

Over the past decade, central bank gold reserves have significantly increased, reversing a 40-year trend of decline. The shift that began around the time of the 2008-09 Global Financial Crisis is depicted in Figures 2 and 3, highlighting the transition from a pre-crisis period of more countries selling gold, to a post-crisis period where more countries have been purchasing gold.

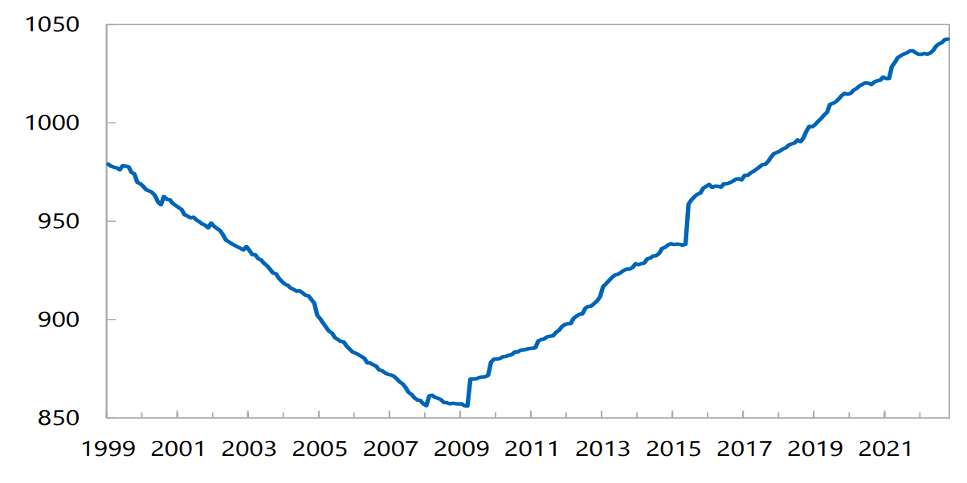

Figure 2. Gold Holdings in Official Reserve Assets, 1999-2022 (million fine Troy ounces).

Source: IMF, International Financial Statistics.

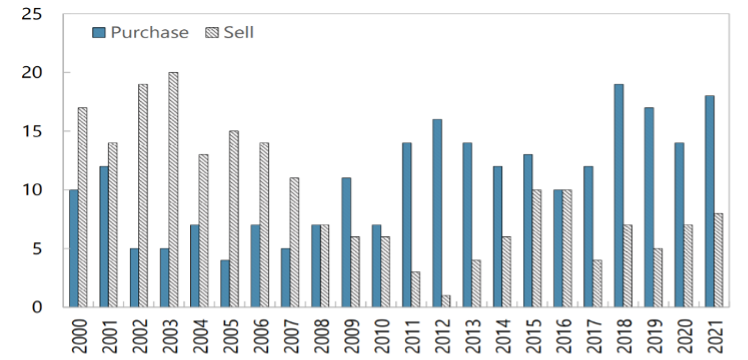

Figure 3. Number of Countries Purchasing/Selling Monetary Gold, 2000-2021 (at least 1 metric ton of gold in a given year).

Source: IMF, International Financial Statistics.

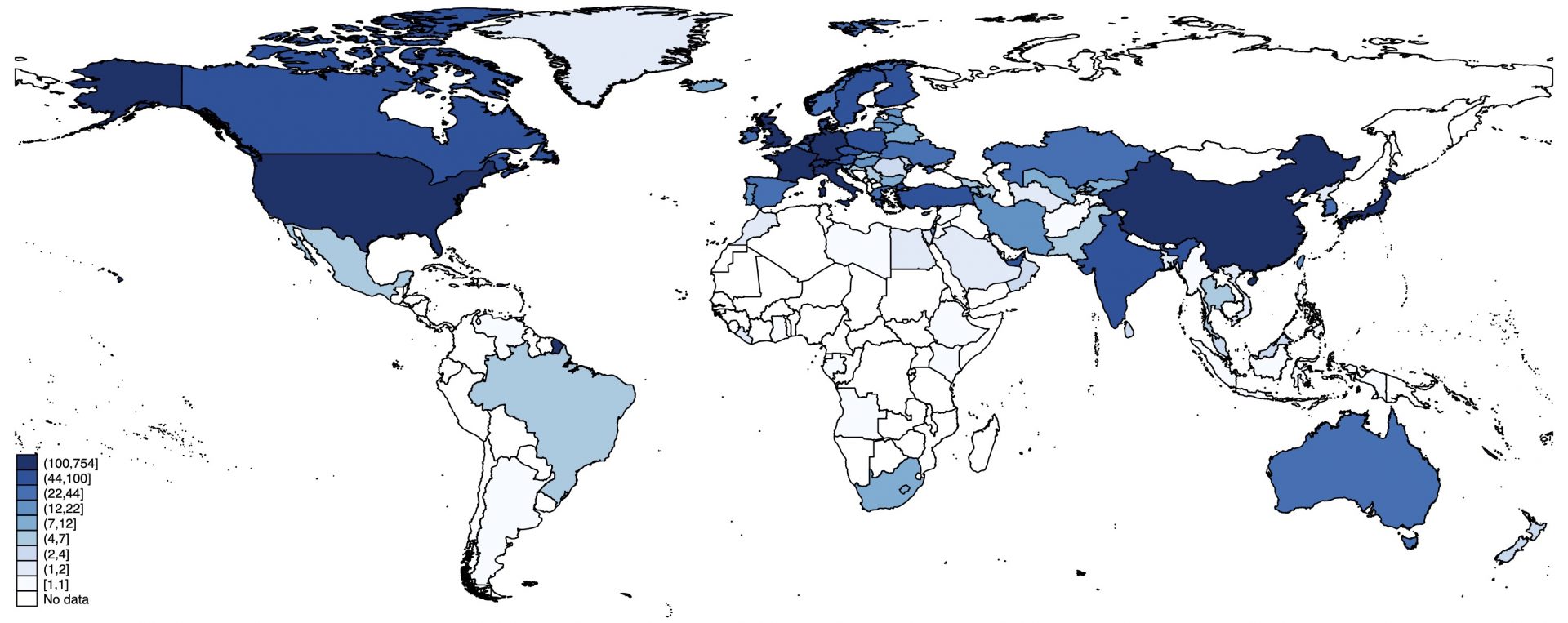

In 2023, central banks added a considerable amount of gold to their reserves. The largest purchases have been reported for China, Poland, and Singapore, with these nations collectively dominating the gold buying landscape during the year.

China is one of the top buyers of gold worldwide. In 2023, the People’s Bank of China emerged as the top gold purchaser globally, adding a record 225 tonnes to its reserves, the highest yearly increase since at least 1977, bringing its total gold reserves to 2,235 tonnes. Despite this significant addition, gold still represents only 4 percent of China’s extensive international reserves.

The National Bank of Poland was another significant buyer in 2023, acquiring 130 tonnes of gold, which boosted its reserves by 57 percent to 359 tonnes, surpassing its initial target and reaching the bank’s highest recorded annual level.

Other central banks, including the Monetary Authority of Singapore, the Central Bank of Libya, and the Czech National Bank, also increased their gold holdings, albeit on a smaller scale. These purchases reflect a broader trend of central banks diversifying their reserves and enhancing financial security amidst global economic uncertainties.

Conversely, the National Bank of Kazakhstan and the Central Bank of Uzbekistan were notable sellers, actively managing their substantial gold reserves in response to domestic production and market conditions. The Central Bank of Bolivia and the Central Bank of Turkey also reduced their gold holdings, primarily to address domestic financial needs.

The U.S. continues to hold the world’s largest gold reserve (25.4 percent of total gold reserves), which underscores the metal’s enduring appeal as a store of value among the world’s leading economies. The U.S. is followed by Germany at 10.5 percent, and Italy and France at 7.6 percent respectively. At present, around one-eighth of the world’s currency reserves comprise of gold, with central banks collectively holding 20 percent of the global gold supply (NBG, 2024).

Why Central Banks are Buying Gold Again

A 2023 World Gold Council survey (on central banks revealed five key motivations for holding gold reserves: (1) historical precedent (77 percent of respondents), (2) crisis resilience (74 percent), (3) long-term value preservation (74 percent), (4) portfolio diversification (70 percent), and (5) sovereign risk mitigation (68 percent). Notably, emerging markets placed a higher emphasis (61 percent) on gold as a “geopolitical diversifier“ compared to developed economies (45 percent).

However, the increasing use of the SWIFT system for sanctions enforcement (e.g., Iran in 2015 and Russia in 2022) has introduced a new factor influencing gold purchases of some governments: safeguarding against sanctions (Arslanalp, Eichengreen and Simpson-Bell, 2023).

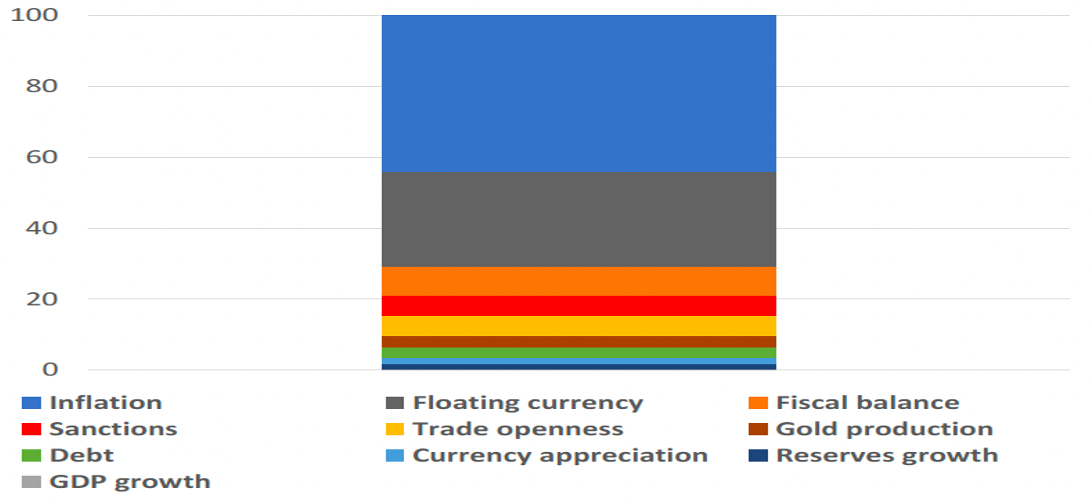

In addition, Arslanalp, Eichengreen, and Simpson-Bell (2023) conclude that central banks’ decisions to acquire gold are primarily driven by the following factors; inflation, the use of floating exchange rates, a nation’s fiscal stability, the threat of sanctions, and the degree of trade openness (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Determinants of Gold Shares in Emerging Market and Developing Economies.

Source: Arslanalp, Eichengreen, and Simpson-Bell (2023).

Gold as a Hedging Instrument

Gold is considered a safe haven and an attractive asset in periods of significant economic, financial, and geopolitical uncertainty (Beckman, Berger, & Czudaj, 2019). This is particularly relevant when returns on reserve currencies are low, a scenario prevalent in recent years.

A hedge against inflation: Inflation presents a significant challenge for central banks, as it erodes the purchasing power of a nation’s currency. Gold has been a long-standing consideration for central banks as a potential inflation hedge. Its price often exhibits an inverse relationship with the value of the US dollar, meaning it tends to appreciate as the dollar depreciates. This phenomenon can be attributed to two primary factors: (1) increased demand during inflationary periods; and (2) gold tends to have intrinsic value unlike currencies (Stonex Bullion, 2024).

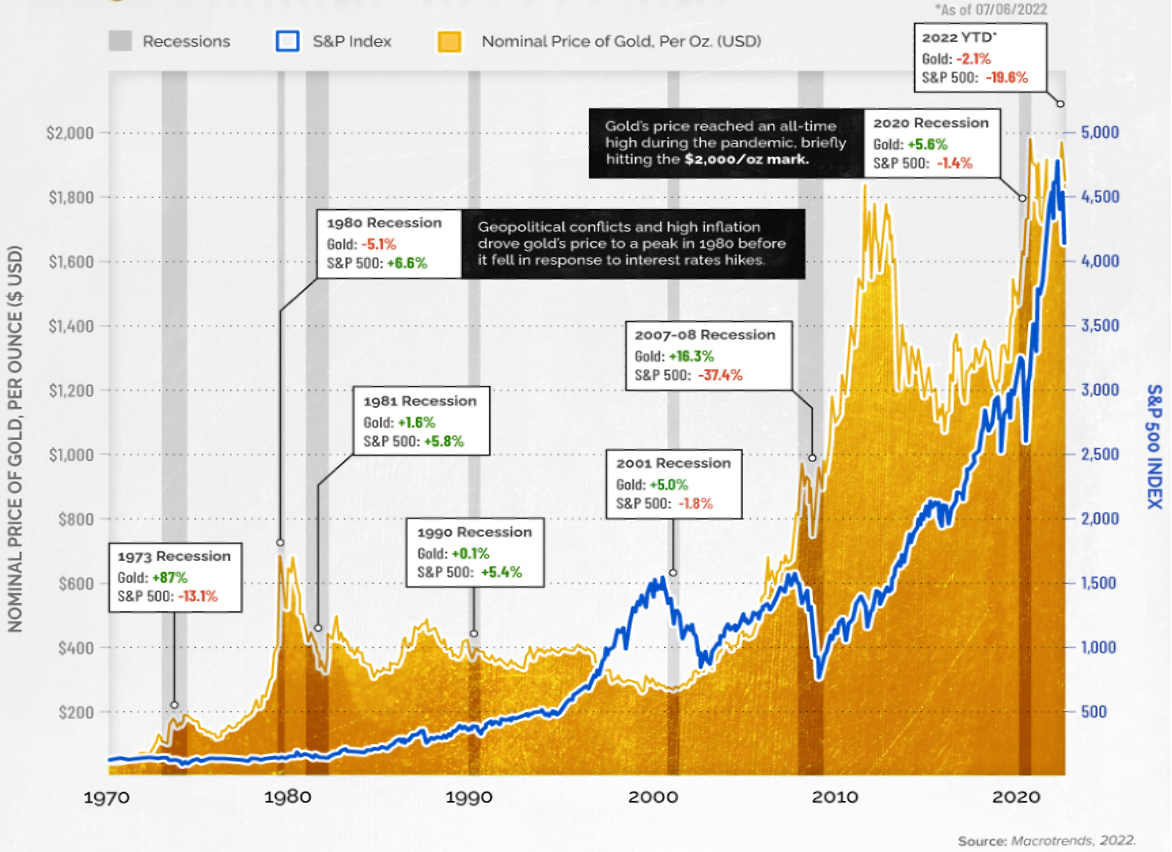

Diversification of portfolio: Diversification is a cornerstone principle of portfolio management. It involves allocating investments across various asset classes to mitigate risk. Gold, with its negative correlation to traditional assets like stocks and bonds, can be a valuable tool for portfolio diversification. In simpler terms, when stock prices decline, gold prices often move in the opposite direction, offering a potential hedge against market downturns (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. How Gold Performs During Recession, 1970-2022.

Source: Bhutada (2022).

Hedge against geopolitical risks: de Besten, Di Casola and Habib (2023) suggest that geopolitical factors may have influenced gold acquisitions for some central banks in 2022. A positive correlation appears to exist between changes in a country’s gold reserves and its geopolitical proximity to China and Russia (compared to the U.S.) for countries actively acquiring gold reserves. This pattern is particularly evident in Belarus and some Central Asian economies, suggesting they may have increased their gold holdings based on geopolitical considerations.

Low or Negative Interest Rates: When interest rates on major reserve currencies like the US dollar are low or negative, it reduces the opportunity cost of holding gold (gold is a passive asset that does not generate periodic income, dividends, and interest benefits). In other words, gold becomes a more attractive option compared to traditional investments that offer minimal or no returns. The prevailing low-interest rate environment, particularly for major reserve currencies like the US dollar, has diminished the opportunity cost of holding gold.

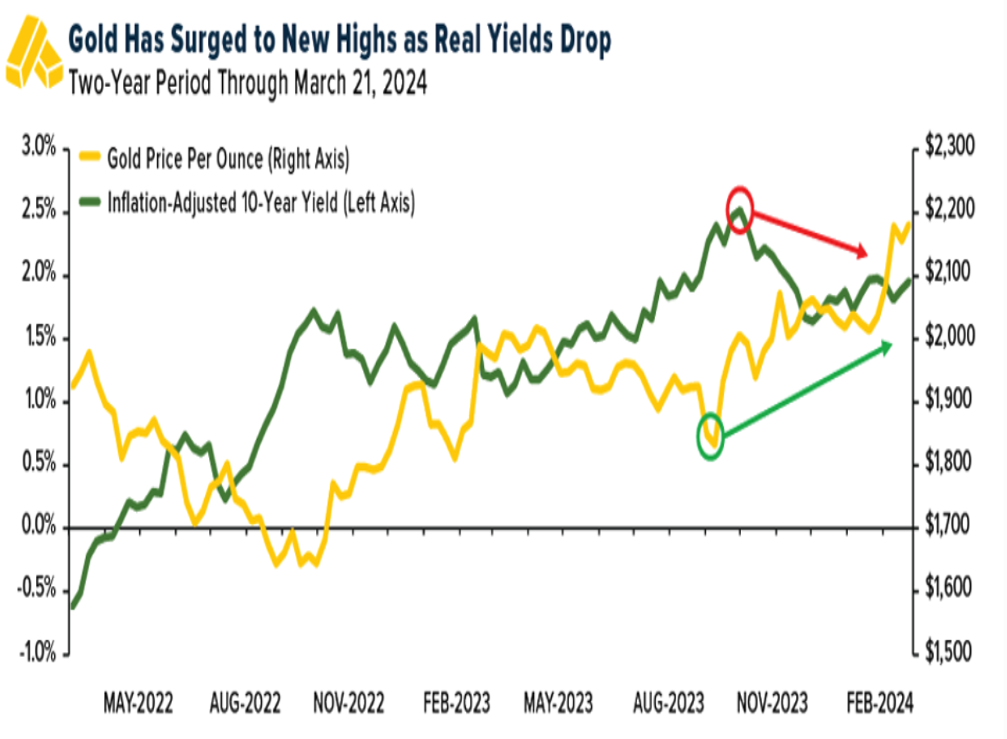

This phenomenon applies to both advanced economies and emerging market economies (EMDEs). Notably, EMDEs with significant dollar-denominated debt are particularly sensitive to fluctuations in US interest rates. Arslanalp, Eichengreen, and Simpson-Bell (2023) conclude that reserve managers are increasingly incorporating gold into their portfolios when returns on reserve currencies are low. Figure 6 illustrates the inverse relationship between the price of gold and the inflation-adjusted 10-year yield.

Figure 6. Gold Price and Inflation-Adjusted 10-Year Yield.

Source: Bloomberg, U.S. Global Investors.

In addition to its aforementioned advantages, gold offers central banks a long-term investment opportunity despite its lack of interest payments, unlike traditional securities. While gold exhibits short-term price volatility, its historical price trend suggests a long-term upward trajectory (see Figure 7).

Figure 7. Gold Price per Troy Ounce (approximately 31.1 grams), in USD.

Source: World Gold Council.

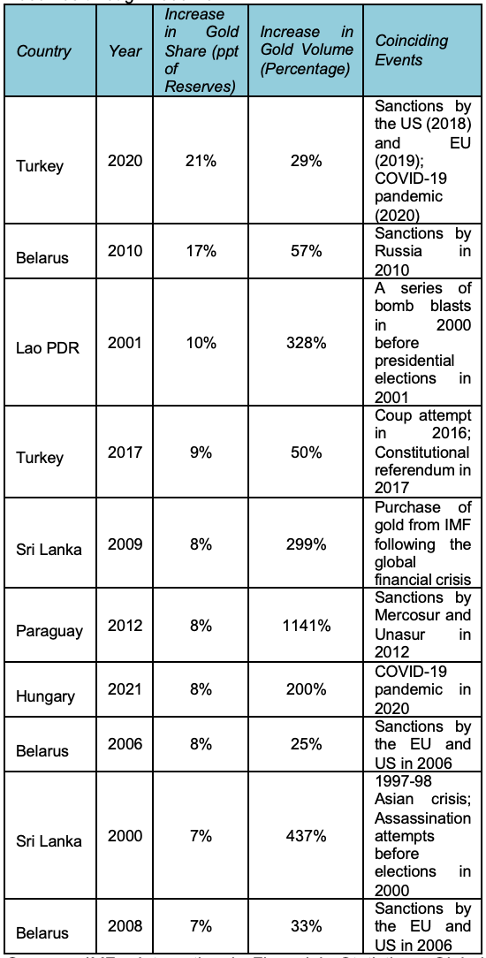

Gold as a Safeguard Against Sanctions

Gold is perceived as a secure and desirable reserve asset in situations where countries face financial sanctions or the risk of asset freezes and seizures (see Table 1). The decision by G7 countries to freeze the foreign exchange reserves of the Bank of Russia in 2022 highlighted the importance of holding reserves in a form less vulnerable to sanctions. Following Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, the Bank of Russia intensified its gold purchases. By 2021, it had confirmed that its gold reserves were fully vaulted domestically. The imposition of sanctions on Russia, which restrict banks from engaging in most transactions with Russian counterparts and limit the Bank of Russia’s access to international financial markets, further underscores the appeal of gold as a safeguard.

While the recent sanctions imposed by G7 countries, which limit Russian banks from conducting most business with their counterparts and restrict the Bank of Russia from accessing its reserves in foreign banks, are an extreme example, similar sanctions have previously impacted or threatened financial operations of other nations’ central banks and governments. This situation raises the question of whether the risk of sanctions has influenced the observed trend of countries’ increasing their gold reserves (IMF, International Financial Statistics, 2022).

Table 1. Top 10 Annual Increases in the Share of Gold in Reserves, 2000-2021.

Source: IMF, International Financial Statistics; Global Sanctions Database (GSDB). Note: Excludes countries with central bank gold purchases from domestic producers.

As outlined in Arslanalp, Eichengreen and Simpson-Bell (2023), there were eight active diversifiers into gold in 2021, each purchasing at least 1 million troy ounces (Kazakhstan, Belarus, Turkey, Uzbekistan, Hungary, Iraq, Argentina, Qatar), exhibiting distinct international economic or political concerns. Kazakhstan, Belarus, and Uzbekistan maintain ties with Russia through the Eurasian Economic Union. Turkey has faced sanctions from both the European Union and the U.S. Iraq has experienced disputes with the U.S., while Hungary has faced similar issues with the European Union. In 2017-21, Qatar was subjected to a travel and economic embargo by Saudi Arabia and neighboring countries. Argentina may have had concerns about asset seizures by foreign courts due to sovereign debt disputes.

Furthermore, according to the Economist (2022), gold is costly to transport, store, and protect. It is expensive to use in transactions and doesn’t earn interest. However, it can be lent out like currencies in a central bank’s reserves. When lent out or used in swaps (where gold is exchanged for currency at agreed dates), it can generate returns. But banks prefer gold to be stored in specific places like the Bank of England or the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, which brings back the risk of sanctions. For instance, During the Iranian Revolution in 1979 and the subsequent hostage crisis, the United States froze Iranian assets, including the gold reserves held in U.S. banks (Arslanalp, Eichengreen and Simpson-Bell, 2023). The National Bank of Georgia intends to transport its acquired gold from England to Georgia for storage, which could potentially reduce storage costs, but further decrease liquidity.

Arslanalp, Eichengreen, and Simpson-Bell (2023) conclude that since the early 2000s, half of the significant year-over-year increases in central bank gold reserves can be attributed to the threat of sanctions. By examining an indicator that tracks financial sanctions by major economies like the United States, United Kingdom, European Union, and Japan, all key issuers of reserve currencies, the authors have confirmed a positive correlation between such sanctions and the proportion of reserves held in gold. Furthermore, their findings suggest that multilateral sanctions imposed by these countries collectively have a more pronounced effect on increasing gold reserves than unilateral sanctions. This is likely because unilateral sanctions allow room for shifting reserves into the currencies of other non-sanctioning nations, whereas multilateral sanctions increase the risks associated with holding foreign exchange reserves, thus making gold a more attractive option.

The NBG’s Historic Decision

The National Bank of Georgia’s (NBG) recent acquisition of gold for its reserves is likely motivated by a desire to diversify its portfolio and hedge against inflation and geopolitical risks. However, recent developments in Georgia raise questions about the timing of this policy decision, bringing political considerations into the picture.

Among these developments is the 2023 suspension of the IMF program for Georgia, due to concerns about the NBG’s governance (Intellinews, 2023). The amendments to the NBG law in June 2023, which created a new First Deputy and Acting Governor position – superseding the existing succession framework – contradicted IMF Safeguards recommendations and raised concerns about increased political influence (International Monetary Fund, 2024). How the recent gold purchase reflect on the future of IMF cooperation is thus a relevant question to ask.

Another ground for concern is the recent approval by the Georgian Parliament of the anti-democratic “Foreign Influence Transparency” law and the anti-Western rhetoric of the ruling party, which have sparked intensive public protests. European partners warn that the law will not align with Georgia’s European Union aspirations and that it could potentially hinder the country’s advancement on the EU pathway. Rather, the law might distance Georgia from the EU. This law has also increased the concerns for further sanctions on members of the ruling party, government officials, and individuals engaging in anti-West and anti-EU propaganda.

Furthermore, the recent amendment of the Tax Code, the so-called “offshores law” allows for tax-free funds transfers from offshore zones to Georgia. This, combined with other developments, raises questions about whether the government is preparing for potential sanctions, should its relationship with Russia continue to strengthen.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this policy brief highlights that central banks’ acquisition of gold reserves, especially in emerging economies, is motivated by a combination of economic and political factors. The economic incentives include the need for portfolio diversification and protection against inflation and geopolitical instabilities, a trend that became more pronounced following the 2008 global financial crisis. Politically, the accumulation of gold serves as a strategic move to lessen dependency on the U.S. dollar and as a defensive measure against potential international sanctions, as highlighted by the post-2014 geopolitical shifts following Russia’s annexation of Crimea.

In 2024, Georgia purchased gold for the first time since regaining its independence. While its gold purchasing strategy seems to align with these economic motives, the recent domestic political dynamics suggest a deeper, possibly strategic political rationale by the National Bank of Georgia. The imposition of U.S. sanctions on key figures, and recent legislative actions deviating from European Union standards, all amidst increasing anti-Western sentiment, indicate that the NBG’s gold acquisitions might also be driven by a quest for greater safeguard against potential future sanctions. Thus, while economic reasons for the purchase are significant, the political underpinnings in the NBG’s recent actions raise numerous unanswered questions.

References

- Arslanalp, S., Eichengreen, B., & Simpson-Bell, C. (2023). Gold as International Reserves: A Barbarous Relic No More? IMF Working Papers.

- Beckman, J., Berger, T., & Czudaj, R. (2019). Gold Price Dynamics and the Role of Uncertainty. Quantitative Finance , 663-681.

- Bhutada G. (2022). Does Gold’s Value Increase During Recessions? Elements Visualcapitalist.

- de Besten, T., Di Casola, P., & Habib M. M. (2023). Geopolitical fragmentation risks and international currencies. The international role of the euro.

- The Economist. (2022). Why gold has lost some of its investment allure. https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2022/01/08/why-gold-has-lost-some-of-its-investment-allure

- International Monetary Fund (2024). Georgia: 2024 Article IV Consultation-Press Release; Staff Report; and Statement by the Executive Director for Georgia. IMF Country Reports 24/135

- Intellinews. (2023). https://www.intellinews.com/georgia-s-national-bank-president-confirms-suspension-of-imf-programme-294545/

- StoneX Bullion (2024). Why Central Banks Buy Gold.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in policy briefs and other publications are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect those of the FREE Network and its research institutes.

Stockholm Institute of Transition Economics Celebrates Its 35th Anniversary

June 15, 2024, marks a significant milestone for the Stockholm Institute of Transition Economics (SITE) as it celebrates its 35th anniversary. Over the past three and a half decades, SITE has established itself as a leading institution dedicated to economic research and the development of policies for transition economies.

From its beginnings as Östekonomiska Institutet in 1989, under the leadership of Anders Åslund, to the rebranding as SITE in 1996 with Erik Berglöf at the helm, SITE has continuously evolved as a research institution, securing a position among the world’s top think tanks in the field of economics, with a focus on Eastern Europe. In 2006, Torbjörn Becker brought his expertise from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to lead SITE into a new era of research excellence, strengthening the focus on institution-building in the region.

Reflecting on this anniversary, Torbjörn Becker, Director of SITE, says:

“As we celebrate 35 years of economic research, policy analysis, and institution building, we are reminded of how important it is that we continue to work in this region. I am particularly proud that we are able to work with our fantastic partners in the FREE Network that make significant contributions to how their respective countries reform and develop.”

Building Institutions for Change

Since its foundation in 1989, SITE has been at the forefront of economic research and policy development in transition economies, playing a crucial role in establishing independent think tanks and academic institutions in Belarus, Georgia, Latvia, Poland, Russia, and Ukraine. These research institutes collectively established the Forum for Research on Eastern Europe and Emerging Economies (FREE Network); an umbrella organization that fosters collaboration and mutual learning among researchers, as well as administrative and institutional capacity building. As one of its key initiatives, the network publishes weekly policy briefs addressing contemporary economic policy challenges in Eastern Europe and emerging markets.

Bridging the Gap Between Research and Policy Making

SITE’s ambition for the years to come remains unchanged: to bridge the gap between leading academic research and current policy making through debate and communication. At our flagship events, such as SITE Development Day and the SITE Academic Conference, we are committed to debating topics where research can pave the way to solving global and regional challenges. In our weekly seminars and regular workshops, we remain dedicated to exchanging ideas with leading experts and policymakers. In the last decades, SITE’s research has been cited by top journals in economics, while its impact beyond academic journals has resulted in more than 30 million impressions across local and international news.

Key Milestones in SITE’s History

Succession Dynamics in Latvian Family Firms

This policy brief examines the emergence, succession, and performance of first-generation family firms in Latvia, highlighting the unique challenges and achievements of these businesses since the early 1990s. Following Latvia’s independence, many family firms were established, providing a natural setting to study succession issues. Key findings reveal that initially, nearly half of these firms did not have a majority stake held by the founding family, but within the first few years after founding, families accumulated majority ownership. It typically took seven years for family ownership to exceed 75 percent. However, 23 years later, only 16 percent of the sample firms have second-generation shareholders. Notably, around 80 percent of these firms remain majority-owned and managed by their founders. Furthermore, family firms outperform non-family firms by 3.1 percent in return on assets (ROA). The findings underscore the need for policies that support effective succession planning, incentivize family-owned business sustainability, and provide targeted training for future generations to maintain the robust economic contributions of these firms.

Introduction

Family firms, where key decisions are controlled by individuals linked by blood or marriage, are the predominant organizational form worldwide. These firms face critical challenges, (e.g. leadership transition, generational differences, emotional ties to the business, and estate planning tax considerations) particularly during ownership succession, which is the transition from the first to the second generation of family members. This issue is especially relevant in Eastern European countries like Latvia, where the shift from a planned to a market economy in the 1990s created the first generation of family firms now approaching generational change.

Understanding how family firms manage this transition is crucial for policymakers, business leaders, and researchers. This policy brief highlights the key findings of a study (Pajuste and Berzins (2024) on Latvian family firms, focusing on ownership succession patterns, the involvement of the next generation, and the impact on firm performance.

Succession Patterns and Ownership Evolution

In Latvia, many family firms began with founders holding minority stakes, reflecting financial constraints and economic uncertainties. Over time, families gradually increased their ownership stakes, demonstrating resilience and strategic planning. On average, it took seven years for family ownership to exceed 75 percent. This gradual ownership increase helped families navigate the challenges of economic transitions and limited access to external capital. The study also reveals that 23 years after being founded, only 16 percent of the sample firms have second-generation family members as shareholders.

Involvement of the Second Generation

The emergence of the second generation in family firm ownership is a pivotal phase. Succession planning and the transmission of familial values, knowledge, and entrepreneurial ethos are crucial during this period. By 2022, only 14 percent of the sample family firms had significant second-generation involvement (defined as the second generation holding a majority of the family shares and having a board seat).

More specifically, in a sample of 266 family firms, 20 percent had involved the second generation in ownership by 2022, with significant involvement in 71 percent of these cases. At the same time, 80 percent of the firms were still majority-owned and managed by the founders. This slow involvement of the second generation highlights the challenges of succession planning and the need for a strategic approach – both from a company and a legal perspective – to ensure a smooth transition from the first to second generation.

Importantly, despite this slow transition, family firms tend to perform better than non-family firms, with a 3.1 percent higher return on assets (ROA). However, within family firms, the involvement of the second generation does not significantly impact firm performance.

Policy Implications and Recommendations

The findings of this study have several important implications for policymakers, business leaders, and researchers.

Support for Succession Planning

There is a need for policies and programs that support succession planning in family firms. This includes providing resources and guidance for families to develop succession plans, ensuring the continuity of family businesses. Ensuring some form of succession, whether within the family or through external parties, is crucial to prevent these firms from closing. Facilitating succession and supporting the survival of these firms would not only protect jobs, but also have a positive economic effect as family firms outperform their non-family counterparts.

Financial Support and Access to Capital

Another way to enable smoother transition and growth for family firms is to improve their access to capital to help them overcome financial constraints. Financial institutions and government programs should focus on providing tailored financial products for family businesses. By doing so, they not only support the longevity of these businesses but also help in maintaining employment levels and preventing the economic fallout from family firm closures.

Education and Training

Educational programs and training for the next generation of family business leaders are essential. These programs should focus on leadership, management, and the unique challenges of family businesses, preparing the next generation for successful transitions.

Awareness and Best Practices

Raising awareness about the importance of succession planning and sharing best practices can help family firms navigate generational transitions more effectively.

Research and Data Collection

Continued research and data collection on family firms and their succession patterns are crucial. This helps in understanding the challenges and opportunities faced by family businesses, informing policies and practices that support their continuation and success.

Conclusion

Latvian family firms, like their counterparts worldwide, face significant challenges during ownership succession. This study highlights the gradual and strategic increase in family ownership stakes, the slow emergence of the second generation in ownership, and the need for comprehensive succession planning. Policymakers, business leaders, and researchers must work together to support family firms in navigating these transitions, ensuring their continued contribution to the economy.

Effective succession planning is crucial for sustaining family businesses across generations, preserving their legacy, and promoting economic growth. By addressing the unique challenges faced by family firms, we can create a supportive environment that fosters the longevity and success of these vital enterprises.

Acknowledgment

This brief is based on an academic article Family Firm Succession: First-generation transitions in Latvia co-authored with Janis Berzins and forthcoming in Finance Research Letters. We acknowledge financial support from the EEA research grant Global2micro (S-BMT-21-8, LT08-2LMT-K-01-073).

References

- Pajuste, A., and Berzins, J. (2024). Family firm successions: First-generation transitions in Latvia. Finance Research Letters, 64, forthcoming.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in policy briefs and other publications are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect those of the FREE Network and its research institutes.

A Gender Perspective on Financing for Development

Gender equality should be considered a global public good due to its extensive benefits for both society and the environment. Investing in gender equality as a global public good necessitates a coordinated international effort, which should be a focal point in discussions on the future of development financing. The upcoming Fourth International Conference on Financing for Development (FfD) in 2025 in Madrid, Spain, provides a crucial opportunity to assess the progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and allow countries to refine their strategies. However, recent background documents lack an explicit focus on opportunities for advancing gender equality, which was also inadequately addressed in the Addis Ababa Action Agenda formulated at the previous FfD conference in 2015. This brief is based on the first of a series of roundtables, organized by the Center for Sustainable Development (CSD) at Brookings, aimed at providing inputs on this critical topic in the lead-up to the Madrid conference.

Financing for development relies on three main pillars: domestic resource mobilization; development assistance; and other sources of international financing. The latter category includes both private and public sources that emerge in response to the need for a global safety net and social protection system, especially in light of increasing risks from pandemics and climate-related shocks. This policy brief is an attempt to highlight how gender considerations may integrate into each of these pillars. It builds on insights from the first Center for Sustainable Development roundtable, discussing this important issue in preparation for the Fourth International Conference on Financing for Development in 2025.

Domestic Resource Mobilization

Fiscal policy plays a critical role in addressing gender gaps, particularly in low-income economies with limited fiscal space. Fiscal policies, including tax systems and public spending, must be designed to consider their gender-specific impacts. For the spending side, several initiatives are promoting tools like gender responsive budgeting, as has been recently discussed in a FROGEE policy paper by Anisimova et al. 2023, on the case of Ukraine.

One key area caregiving services. Caregiving, whether for children, the elderly, or other dependents, disproportionately affects women (see another FREE Network brief by Akulava et al. 2021) and remains largely invisible in economic policies. Many countries, especially outside of higher-income economies, lack universal caregiving services and infrastructure. This sector is significant for economic development and resilience, especially in the context of climate change, which is expected to increase the demands on caregiving due to displacement and health-related challenges. Therefore, integrating care into fiscal policy discussions is not only about gender equality but also about economic resilience and climate adaptation.

To address unpaid care work effectively, it is necessary to integrate care into public finance systems. This can involve developing public caregiving infrastructure and services that support both paid and unpaid caregivers. One first step in this direction would be the monitoring of household time-budgets, to start understanding and analyzing the supply of caregiving services that currently is largely undocumented.

Another policy area crucial for supporting women are social protection policies. In particular policies such as parental leave and childcare support can help reduce gender disparities in the labor market (see examples in the FREE Network brief by Campa, 2024). By providing a safety net, social protection policies enable women to participate more fully in economic activities without the constant threat of financial insecurity.

A specific challenge of the developing world in this respect is the fact that many women work in the informal sector and thereby lack access to social security benefits, leaving them vulnerable during economic hardships. Economic development alone does not solve this issue, as even many developed and wealthy countries lack comprehensive social protection systems. Therefore, a specific effort is needed to develop inclusive social protection systems that cover informal workers, ensuring women have access to benefits such as pensions, healthcare, and unemployment insurance.

Much less discussed is the integration of gender concerns in the taxation side of fiscal policy. Progressive taxation, where tax rates increase with higher income levels, is particularly beneficial for women, who are overrepresented in lower income quintiles. A progressive tax system can thus, besides helping redistribute wealth more equitably, also support gender equality.

Effective tax administration is crucial for improving compliance and maximizing revenue collection. However, it is particularly important in this context to design tax systems that minimize the compliance burden on low-income and informal sector workers, many of whom are women. This can be achieved by simplifying tax procedures and providing support for small and micro enterprises to navigate the tax system. The potential of digital tax systems is significant in this regard (Okunogbe, 2022). Digitalization can streamline tax collection, reduce administrative costs, and improve compliance. However, there are challenges associated with digital tax systems, particularly in ensuring accessibility for all citizens. Women, especially those in rural areas and with lower literacy levels, may face significant barriers in accessing and utilizing digital tax systems. Therefore, while digitalization offers many benefits, it must be implemented in a way that is inclusive and equitable. This includes providing digital literacy training and ensuring that digital tax platforms are user-friendly and accessible to all segments of the population.

Health taxes, such as those on tobacco, alcohol, and sugar-sweetened beverages, may also play a role in promoting gender equity. These taxes help reduce consumption of harmful products, which are disproportionately consumed by men and heavily affect household budgets. By discouraging the use of such products, health taxes can redirect household spending towards more beneficial areas, such as education and healthcare, which are often prioritized by women.

Moreover, health taxes can generate significant revenue that can be reinvested in gender-responsive public spending. For instance, funds raised from health taxes can be allocated to healthcare services, including reproductive health and maternal care, which directly benefit women. Additionally, excise taxes on harmful products address externalities, improving overall public health and reducing the burden on women who often provide unpaid health care.

Broader Sources of Financing for Social Services

The increasing risks from pandemics, climate-related shocks, food insecurity, and other economic shocks of a global nature highlight the need for a global safety net and social protection system. This in turn raises additional demand for effective financing for social services. One area in which new sources of international funding can be found is the emerging global infrastructure for climate finance.

Climate Finance and Gender Equality

Climate finance presents a unique opportunity to address gender equality, particularly in the context of climate adaptation and mitigation strategies. Due to (among others) resource constraints, unequal land ownership and unevenly distributed family responsibilities, women are often more vulnerable to climate impacts. Integrating gender considerations into climate adaptation and mitigation strategies ensures women are supported in building resilience.

One key approach is to use climate finance to promote economic diversification for women, especially in sectors like agriculture, where they play a significant role. For example, providing female farmers with access to capital, training, and resources to adopt climate-resilient agricultural practices can improve their economic security and reduce their vulnerability to climate shocks. This includes supporting transitions to sustainable farming methods, such as crop diversification, agroforestry, and improved irrigation techniques.

Additionally, climate finance can support the development of climate-resilient infrastructure that benefits women. This includes investments in clean energy, water management systems, and transportation networks that are essential for their daily activities and livelihoods. Ensuring that women have access to and can benefit from these infrastructures is crucial for their overall well-being and economic empowerment.

Women can play a pivotal role in natural resource management and environmental conservation. Research has shown that involving women in the management of natural resources, such as forests and water bodies, may lead to more sustainable and equitable outcomes. Women tend to prioritize long-term sustainability and community benefits, which can enhance the effectiveness of conservation efforts (see Agarwal, 2010. For a more nuanced view, see Meinzen-Dick, Kovarik and Quisumbing, 2014).